When we scratch a record, it’s a tragedy. when Milan Knížák scratched a record, it became highly collectible art. Our resident archivist explains the strange world of broken music

I recently went to an exhibition at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco called ‘Art & Vinyl’. It pulled together record sleeves that had been created by artists, or that artists had contributed to. So there are records with covers that Warhol worked on, the obvious ones by The Velvet Underground and The Rolling Stones, a record from 1949 by Paul Robeson, ‘Songs Of Peace’, which had a Picasso painting of a dove printed directly onto the vinyl.

Kraftwerk’s ‘Ralf & Florian’ was there courtesy of the photograph on the cover being taken by Robert Franck. They didn’t include the first Kraftwerk album, which has a photograph on the inside of the gatefold of an electricity substation shot by Bernd and Hilla Becher who were conceptual artists and photographers, but as the photo was used on the inside, maybe it didn’t count.

The book that was published to go with the exhibition reminded me of another book I have from a similar exhibition called ‘Broken Music’ from 1979. It was curated by Milan Knížák, there was also a record released at the same time, also called ‘Broken Music’.

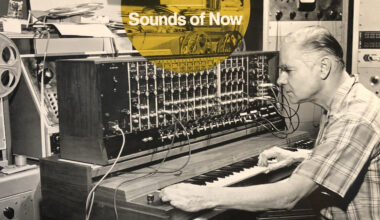

Knížák is a Czech performance artist and musician among other things and he would damage records in all kinds of interesting ways, like sticking them in a toaster. He started in the 1960s, creating happenings with an art collective called Aktual, who would stage events which he called ‘Ceremonies’ and ‘Demonstrations’.

He was a member of Fluxus and was made the director of Fluxus East and organised an event in Prague in 1966 called ‘Killing The Books’ where he laid a carpet out in the street, and started tearing pages out of a book and setting fire to them. He was pretty out there. He was considered a dissident and was under surveillance and harassed by the authorities.

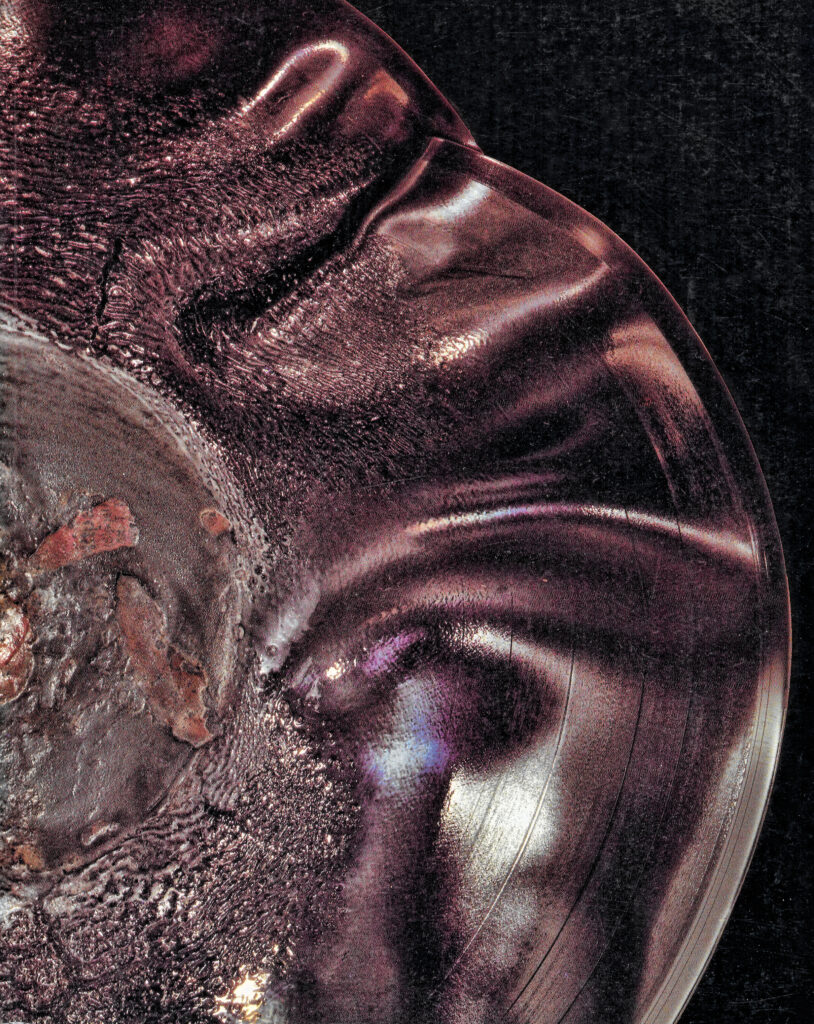

He started messing around with records in 1963. He began by just playing them too slowly or too fast, and by 1965 he was wrecking records, he would scratch them, make holes in them, play them over and over until the they got more damaged, and he would often ruin the stylus and record player itself. As he got into it, he started covering them with tape, burning them and cutting them up and gluing parts of different records together. He thought of these Frankesnstein’s monsters of records as just that – a new record that created fresh compositions from the fragments he’d glued together. In the 1970s, he got involved with the Italian art magazine Flash Art who sold some of his records to well-known artists who hung them on their walls. After that, Knížák started to think of his work as sculptures as well as musical creations.

His work mangling records was a huge influence on Christian Marclay, who’s probably the best-known person working with broken records today. Marclay’s ‘Record Without A Cover’ from 1985 was distributed without a cover, with instructions not to put a cover on it or protect it at all etched onto one side. The build up of scratches and scuffs and other damage on the record was the whole idea, that’s what you were supposed to listen to.

‘Broken Music’ is pretty rare even though it has been re-released. As I write this there’s a copy on Discogs for sale for £250. There was a limited edition boxset released in 1983 on the Edition Hundertmark label, which came with a C60 cassette, a partially melted seven-inch vinyl, which was painted and signed by Knížák , there were just 40 of those made. There was a CD release in the UK in 2005, and a vinyl reissue on Sub Rosa in 2015, which is easy to get hold of at a normal price. It’s well worth tracking down if you’re interested in the roots of turntablism and noise.