Our resident archivist salutes electronica’s unsung heroes, those credited with having “realised” well-known works, and picks out the shining examples

I’ve been thinking about the unsung heroes of electronic music recently. Although these days everyone knows Delia Derbyshire’s name, and associates it with the theme tune to ‘Doctor Who’, far fewer people would be able to name Ron Grainer as the composer. The credits on the record itself say “Composed by Ron Grainer” and in tiny writing “Realised by Delia Derbyshire”.

As a BBC employee, she wouldn’t have received any royalty payments for her work on that piece, and without her input there is no way it would have had anything like the same impact. In fact, you can get an idea of how it might have sounded had it gone ahead without her work on a 1980 album called ‘The Exciting Television Music Of Ron Grainer’. His own arrangement of the ‘Doctor Who’ theme is on there and sounds like the theme tune to a bad Mexican cop show. Had that been the theme used on the TV show, we wouldn’t be talking about it today.

While not quite in the same cultural ballpark, it’s a similar case with Edgard Varèse and his famous piece ‘Poème Électronique’. The piece was commissioned by Phillips for their pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels in 1958. The pavilion itself was designed by Le Corbusier and the music was created for an eight-minute film which he’d put together. Recorded in the Philips Natuurkundig Laboratorium in Eindhoven, the engineer was Dick Raaymakers, and he helped Varèse put together ‘Poème Électronique’. The thing is, if you listen to Raaymakers’ own compositions, they sound just like it. He obviously played a large part in how that piece sounded.

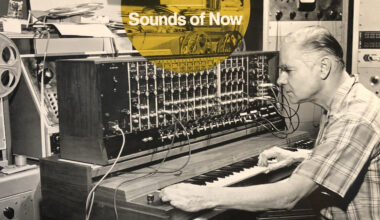

In the RDF Studio For Electronic Music in Cologne there were people like Gottfried Michael Koenig who worked there from 1954 until 1964. He was also a composer, but he assisted Stockhausen, and is credited with the “realisation” of some of his most famous works, like ‘Gesang Der Jünglinge’ and ‘Kontakte’.

In Poland, at the Polish Radio Experimential Studio (Polskie Radio), composers Andrzej Dobrowolski and Włodzimierz Kotoński were also making pieces, and main guy there who was doing a lot of the “realisation” work was Eugeniusz Rudnik. He’s credited on both Włodzimierz Kotoński’s ’Aela’ and on Andrzej Dobrowolski’s ‘Muzyka Na Taśmę Magnetofonową | Obój Soloas’ as “Technician [Realizacja]”. He started out working at the state broadcaster in charge of the plumbers, carpenters and painters, before becoming a technician and then a composer in his own right.

In rock music, the credit tends to be “producer”, but even that often overlooks the work that’s being done by the engineer. For example, David Bowie is credited as the producer on ‘Fame’, but did he really do all the work on the voice? Changing the pitch and keeping it in tune and in time would have been technically very demanding. I expect it was Harry Maslin who took care of that. He went onto produce ‘Station To Station’ and, erm, The Bay City Rollers. He is co-credited as producer on the record, to be fair to Bowie. David Byrne and Brian Eno are credited as producers on ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’, alongside 10 engineers at five different studios.

And I was listening to the demo of ‘She Said, She Said’ by The Beatles the other day, and it was terrible, Lennon all over the place on an acoustic guitar. And then you listen to the finished piece and it’s incredible. We all know how important George Martin was to them, but let’s hear it for the realisers of early electronic music, too!