Our esteemed columnist remembers his adventures with The Prodigy’s Keith Flint…

After 50 years in the rock ’n’ roll trenches, you get used to a high body count, but now electronic music is starting to lose its own, including leading figures from a generation that really shouldn’t be going yet. The news about the untimely death of Keith Flint, The Prodigy’s charismatic firestarter, dancer and occasional singer, came as a real shock. He always seemed so full of life as he strafed the global stage with his Prodigy family Liam and Maxim, his future-shock punk persona always set to stun, his footprint always huge.

Keith’s part in bridging the gap between electronic dance music and punk rock’s original anarchic blast was immeasurable and, as they ensnared new generations, it has proved to be timeless. I’d like to pay tribute to this colossal figure by remembering my own time with The Prodigy.

It was 1995 and my DJing career had hit overdrive level, from Primal Scream tours to bonkers clubs and the Heavenly Social. Sabres Of Paradise’s Nina Walsh asked if I’d like to play at an event in Iceland called Top of the World, along with Scream Team DJ squad, Björk, Bandulu and The Prodigy.

Amidst the flaming tents and mountain disasters, The Prodigy delivered a fearsome set after I’d DJed for a fashion show… on acid… surrounded by stripping models. The ‘Firestarter’ era, so new and terrifying then, had begun. The band were amused how I’d lost my passport and plane ticket, which meant flying back with them in business class. By the end of the journey, Liam had asked if I’d like to try out DJing for them as they wanted to expand their pre-set menu to include punk classics I was spinning before the Scream Team. He asked if I’d like to warm up for a home turf show at Ilford’s fairly intimate Island club (with strict instructions not to play ‘The Smurfs’).

At the time, The Prodigy were about to be catapulted on to the world stage as major contenders, hardcore anthems making way for the punky style that included ‘Firestarter’ and ‘Breathe’. By then, Keith had shorn his locks to a blond spike-top, sporting bondage gear and dog collars while taking to the stage in a huge transparent bubble. Shitting myself in front of the glow stick waving nutters, my trial by fire went like a dream as Pistols and Clash chestnuts joined raging acid techno.

As I always would with The Prodigy, I tried to build the equivalent of a lunatic asylum to set their scene, ‘Anarchy In The UK’ always a winner. Pretty soon, I was doing Blackpool’s Tower Ballroom (after support band The Chemical Brothers), Brixton Academy and the UK tour where they had a whole 1960s front room onstage with armchairs and tacky furniture.

With oxygen tanks at the side of stage, Keith was always mesmerising, possessed as he delivered ‘Firestarter’, usually sporting his yellow Dirty Dozen top. I particularly remember sitting in his room at the Metropole hotel as we prepared to take Brixton; it transpired another reason Liam and Keith wanted me on the tour was to hear my Clash/Pistols war stories. Myself, I wanted to find out what made them tick.

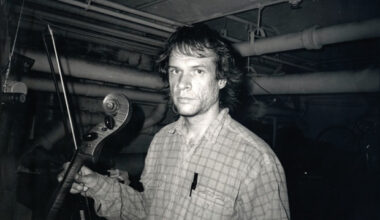

Offstage, Keith was a quiet, always pleasant individual who loved to potter in his Essex garden, holding the door for my then-girlfriend and always taking time out to greet the bunch of nutter mates who always accompanied me to gigs. On first meeting them, he went around shaking every single hand with a big smile.

He said he had to get himself psyched up to transform into the manic entity that lit up the stage. I’d see him doing it behind the stage curtain, running on the spot snarling to himself until he felt ready to take any stage or hell-sewer he was thrown to. The power he could wield over those crowds was often awesome, like he was living their most extreme fantasies for them.

Before one show at the Brighton Centre, he was whizzing around the queue on a jet scooter. Considering their fearsome image, The Prodigy were pussycats, a self-contained family who remained the closest of mates, always little jokes and piss-takes amid a proper bond. I was honoured to be welcomed in for the time I spent with them, Keith always ready with a hysterical antic or comment, usually on a stoned, surreal tip.

Having remixed The Prodigy’s ‘Speedway’, they asked me to punk up their version of L7’s ‘Fuel My Fire’, which I did with guitarist Gizz Butt, but it never got released for various reasons. After dodging missiles in Munich, I parted company with The Prodigy though still ran into them at various times. Keith was special, as many have agreed since his death. Like a raging messiah for electronic music around the globe, his presence is already sorely missed. We’ve all lost a mate.

There’s been much activity on The Orb front as I ease into writing Alex’s biography. He’s completed the amazing ‘Chocolate Hills’ album with Metamono’s Paul Conboy, crafted two heartbreaking remixes of Sendelica’s ‘Windmill’ as a tribute to my late partner Helen, using her speech from the Breaking Convention world psychedelic drugs conference, and remixed the new version of Hawkwind’s ‘Silver Machine’ by New York-London duo Sontaag.

Last heard from in 2014 with their self-titled cinematic “space opera”, Richard Sontaag and Ian Fortnam’s krautrock rampage through Hawkwind’s classic is produced by my old mucker Youth, who also plays bass backed up by former Adam And The Ants drummer Dave Barbarossa. Not only that, the track boasts original sax player Nik Turner, for many the true flag flyer of Hawkwind’s original free-for-all spirit.

Alex’s ‘Imaginarium Translucent JellyFish Dub’ mix stretches to nine minutes, setting the cosmic tone with hip hop beats before taking off into house around the six-minute mark. It’s quite early Orb in flavour, which is hardly surprising seeing as The Orb are currently in full effect, touring the UK to mark their 30th anniversary. I saw the show in Oxford and it was fabulous; still pushing the outer limits of hurling sound at large crowds and propelling them into a rare state of euphoria. Life is actually quite good again at the moment.