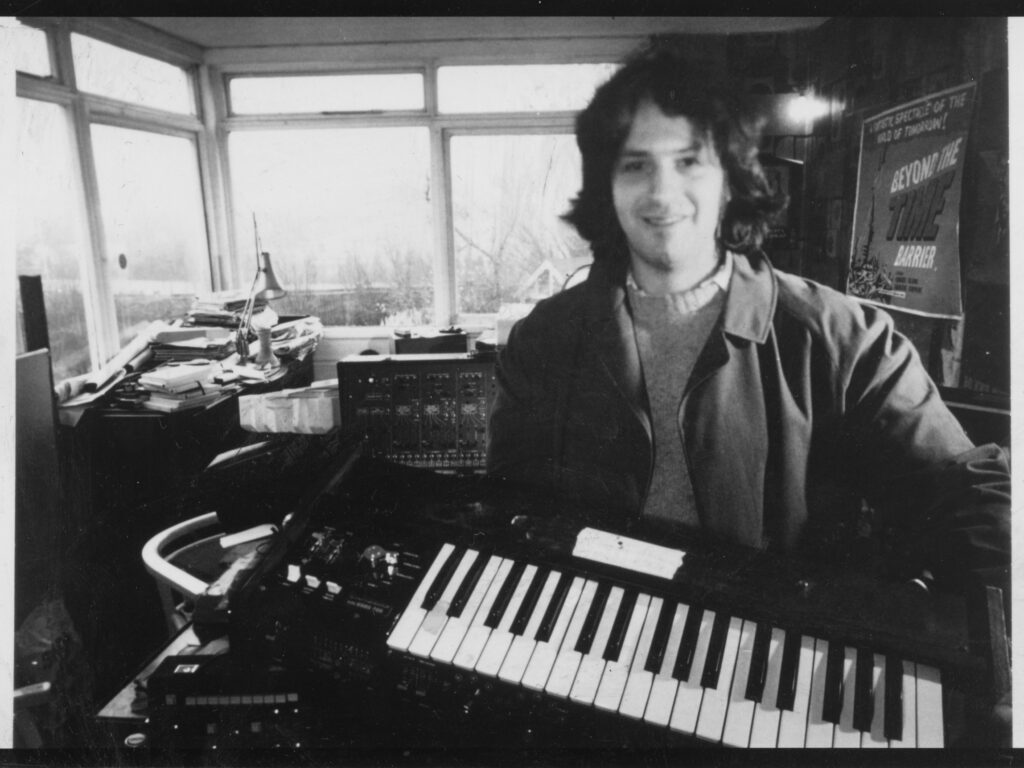

As a recording artist, first as The Normal and then as The Silicon Teens, his career was over in a flash. but as the head honcho of Mute records, Daniel Miller has stayed the course and then some, building one of the greatest labels in the world. and with Mute gearing up for the 2020š and beyond, his vision remains as strong and clear as it ever was. He still has time for a bit of DJing too. no requests please

“I don’t see myself as a businessman. Not really. I know I have to be one sometimes, but I don’t think I’m very good at it. I’ve just been lucky enough to surround myself with people who have been excellent at what they do. You know, good accountants, good lawyers, people like that. I’ve always been much more at home on the creative side of things than the business side.”

Have you ever felt any conflict between being creative and running a business?

“No. Never. Other people have, though. There was one particular finance director we had, a great guy, terrific at his job, he was with us for many years, and I know he often felt there was a lot of conflict in what I was doing. I drove him nuts. Totally nuts. He was always saying to me, ‘Why are you spending money on this?’. I couldn’t answer him half the time.”

Daniel Miller gives a little chuckle. Then a little shrug. Then another little chuckle.

He’s certainly not a conventional businessman, I’ll give him that. But as the boss of Mute Records, Daniel Miller is in charge of one of the most important independent labels in the world. What started as a vehicle for a single recorded by Daniel under the name The Normal in 1978, has given us some of the very best electronic music of the last four decades. Depeche Mode, Yazoo and Erasure. Fad Gadget, DAF and Laibach. Nitzer Ebb, Wire and Renegade Soundwave. Plastikman, Goldfrapp and Moby. Can, Throbbing Gristle and New Order. And that’s just a fraction of the Mute back catalogue. But I don’t need to go on, do I? Of course I don’t.

I’m not here to talk about Mute’s past glories, though. We might touch on one or two of them along the way, but I’m mainly here to get a measure on Daniel Miller himself, a man who is every bit the forward thinker, every inch the futurist, that he was in the early days of his record label.

We’re having lunch in a bustling Japanese-Korean restaurant just down the road from the Mute office in west London. It’s more of a canteen-type place than a posh eaterie – there’s a menu pinned to a board outside which has pictures of some of the dishes – but Daniel is a regular here and the staff know him well. We’ve ordered some drinks – green tea for Daniel – and I’ve started with a couple of innocuous questions, but Mr Mute doesn’t seem in the mood for answering them.

Which isn’t to say he’s not warm and friendly and chatty, he’s all of those and much more, it’s just that, for the first 15 minutes or so, he’s the one doing most of the quizzing. He seems genuinely interested in my responses too. I don’t think I’ve had this from an interviewee before, not to this extent anyway, and it’s quite heartwarming. As well as “futurist”, I also have him down as “charmer” now.

Normal service is only resumed when I steer the conversation round to the current Mute roster. Daniel is very excited about the label’s 2018 release schedule. And with good reason.

“The Chris Carter album we put out a couple of months ago, the ‘Chemistry Lessons’ album, that’s such a good record,” he says. “We’ve obviously had a very long relationship with Chris going back to when we first got the Throbbing Gristle catalogue – 1981 or 1982 maybe – and it’s great to still be working together. So on the one hand we’ve got people like Chris and New Order and A Certain Ratio, people who are, I hesitate to describe them as older, but they’ve been around for a while, and then we’ve got lots of new artists too. It’s a really interesting mixture at the moment.”

As well as not wanting to identify anybody as “old” or “older”, do you also have to be careful about who you describe as “new”?

“Yes, I do,” he laughs. “I still think of Liars as a new band and we’ve been working with them for 20 years. I love Liars. I love what they do and always have done. I still think of Goldfrapp as a new band as well.”

A couple of rather more recent additions to the Mute roster that Daniel mentions as he sips his tea are Chris Liebing and ShadowParty. The latter are something of a supergroup, bringing together Tom Chapman and Phil Cunningham from New Order with Josh Hager and Jeff Friedl from Devo. They’re gearing up to release their debut album next month. Chris Liebing is a stalwart of the German techno scene, working as a DJ, a producer and a podcaster, as well as running his own CLR imprint for many years.

“There’s a Chris Liebing album coming up later in the year, but it’s more of an electronic record than a techno record,” says Daniel. “Around half of it is instrumental, but the other tracks feature guest vocalists. He’s got some great people on there – Gary Numan is on there, Polly Scattergood, Cold Cave – but they’re not singing, they’re doing spoken word stuff. It’s a fascinating album and it has some really unexpected elements to it. I think a lot of people are going to like it.

“I’ve known Chris for a long time and we’re quite close, so I’m pleased to have him on Mute. He’s very open-minded, so you can have an honest discussion with him without him getting defensive. Some artists are like that, so you can just come straight out with something. Polly Scattergood is like that, I can always be totally open and straightforward with her, whereas others you have to spend two months building up to a conversation. It’s not that I want to tell people what to do, and I don’t actually like it when artists do what they’re told, but I do have opinions and I do like to express them. It’s then up to the artist to take what they want from that.”

Like most of us, Daniel Miller first got into music as he hit his teens. The British rhythm & blues scene was at its peak and he notes a particular fondness for The Rolling Stones, whose version of The Crickets’ ‘Not Fade Away’ reached the UK Top Three around the time of Daniel’s 13th birthday. He fancied himself as a guitar player, as did many of the lads at his school in Golders Green, north-west London.

“I was in a lot of bands when I was a kid. Terrible music. Well, not terrible music, but extremely badly played.”

One of his best mates stood apart from the rest, though, a young shaver by the name of Paul Kossoff, who went on to become a founder member of hard rockers Free. Paul Kossoff tragically died in 1976, when he was just 25 years old, but he’s still widely recognised as one of the greatest guitarists of all time.

“Paul was in the same class as me at school,” says Daniel. “I lived round the corner from him and his parents had a garage where we all used to go to practice. He tried to teach me a few things, but I was just hopeless. He started playing electric guitar when he was very young and he was a brilliant classical guitarist as well. I remember him doing a fantastic classical recital at school when we were about 12. He was incredible, even at that age. But we had some other great musicians at the school too. Another of my classmates was Nic Potter, who was in Van Der Graaf Generator.”

It wasn’t until the late 1970s, several years after he’d left school, that Daniel started thinking about making music again. He was several steps into a career in the film and television industry by this point and was working as an assistant film editor at ATV, although he had dipped his toes into the music business a little earlier in the decade.

“I was a DJ at a holiday resort in the mountains in Switzerland for a couple of seasons,” he reveals. “I wasn’t a fan of a lot of the records I played, which was mostly the chart hits of the day, so everything from ABBA to Status Quo, plus lots of oldies and some horrible German schalger. Deep Purple were always a big favourite with that crowd and I also played funk stuff like James Brown and The Fatback Band and BT Express, so it was all over the place in terms of music genres. I remember playing Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’, but that’s as near as it got to electronic music. I really enjoyed the actual experience of DJing, though. I had just two rules for myself – I didn’t play a record twice in one night and I didn’t do requests.

“It wasn’t long after I came back to the UK after my second spell in Switzerland that punk happened. That was a big inspiration for me, it was very exciting, but probably more in terms of the DIY attitude than the sound.

There was also the advent of relatively cheap synthesisers around that same time and I quickly realised that synths were the way forward for me, so I focused on getting as much film work as possible in order to earn enough money to buy a synth and a tape recorder. I worked as hard as I could, working overtime, working freelance, doing anything and everything. I didn’t like a lot of it, but I knew it was the only way for me to make the money I needed. A year and a half later, I was ready to take the plunge.”

“The plunge” was, of course, The Normal’s ‘TVOD’ and ‘Warm Leatherette’ single in October 1978. It was the first release on Mute and remains one of the greatest electronic records of all time, but it soon became clear that Daniel Miller was more focused on his fledgling label than his own recording career. ‘TVOD’ was followed by half a dozen improvised pieces recorded with Robert Rental in March 1979 and issued as the single-sided ‘Live At West Runton Pavilion’ on Rough Trade, but that was it for The Normal.

Daniel subsequently hatched his Silicon Teens project, putting out three singles and the ‘Music For Parties’ album, before hooking up with Wire men Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis for the short-lived Duet Emmo, whose ‘So It Seems’ album came out in 1983. Since then, however, he has restricted his output to production and remix work, which seems astonishing for a man who spends as much time as he can in the recording studio and has an enviable collection of old synths, including his beloved EMS Synthi 100, as well as a growing stack of modular gear.

“I’m not really a musician, you know,” he declares. “I’m not an artist in the way most people would understand it. I mean, in terms of my own personal style, I haven’t really developed much since 1978. And I’m proud of it!”

But you are still making music?

“Just for myself, not to get anything out there, although I have been tempted to work on things to build into my DJ set.”

Daniel is passionate about DJing and has been for the last six or seven years. We’re talking serious club DJing here, not spinning hits like he was in the 1970s. He mostly plays techno and is a regular at Berghain, the legendary Berlin nightspot.

“I love the challenge of putting together a DJ set, finding things that work together and I think are interesting musically,” he says. “When it works, it’s amazing. When you get a connection with the crowd, it’s a great feeling. I also like the people around techno, they’re generally very decent people. Certainly at my level, it doesn’t seem to be at all competitive. I like staying out late too, so that’s another bonus.”

Is it fair to say most of the people that you’re playing to have no idea who you are?

“They don’t, but I’m happy about that. I get the occasional Depeche Mode fan coming along, which is brilliant, as long as they don’t expect me to play the Depeche back catalogue. But for the most part, people don’t know me. Some of them are surprised when they see me play, you know, someone of my age, but I get a lot of positive comments. Actually, with techno, a bit like dub or jazz, I think the older you get, the more that people appreciate you.”

Spending long nights in hot clubs has been a major factor is Daniel’s recent decision to reactivate NovaMute, Mute’s dance music offshoot imprint, and also to launch another business initiative, Noviton, a DJ booking agency and event planning company.

“We did some brilliant stuff on NovaMute back in the day, things like Plastikman and Speedy J, but the label fizzled out in the early 2000s,” says Daniel. “Since I’ve been DJing, it’s made me realise how much I missed it, so I’m pleased we’ve got it going again. Chris Liebing has been very supportive and has helped me out. Richie Hawtin and Matrixxman have been very supportive too. Everybody I spoke to said, ‘Yeah, great, do it’. We’ve had three releases so far, and we’ve got our next three lined up ready to go. We’ve got a new EP from Charlotte De Witte coming up next, then an artist from Brazil called Anna, and then another record from Nicolas Bougaïeff.

“I’m getting lots of demos for NovaMute now that the word is out, but I’m the only one doing A&R for the label and listening isn’t always easy. I mean, I love music, but I have to be in the right mood to be able to listen to something and make a critical judgement about it. That’s the same for everything that I A&R, whether it’s a demo from an unknown artist or a work in progress by an established name on Mute. I’m known for being a bit slow to respond, but it’s essential to be sure about what you think and what you say. It’s a big responsibility to the artist and to the label.”

We’re tucking into our food now. Come to think of it, “tucking in” isn’t exactly an accurate description. Daniel has ordered a tiny watery salad and an equally tiny portion of seaweed, which he somehow manages to make last for around half an hour. “Don’t mind me, I’m on this weird diet at the moment,” he tells me. I’ve gone for a selection of sushi but, as always with me, I’m fighting a losing battle with the chopsticks and end up flinging fish and rice in every direction apart from my mouth. Daniel, bless him, pretends not to notice.

Ahead of this interview, I’ve asked several other journalists what they know about Daniel Miller’s personal life. I’ve largely drawn a blank, just a few loose details about his pre-Mute days, so I’m not sure how willing he’s going to be to answer my next set of questions. I start off by asking about his parents.

“They came to Britain just before the Second World War as refugees from Vienna,” he says. “They managed to get out in time. They met here in London, they didn’t know each other in Vienna. My father was an actor and he set up a cabaret theatre called the Lanterndl, doing political and satirical cabaret for Austrian and German emigres. My mum was a young actress and she got a job there. As well as the theatre productions, they both did propaganda work for the BBC German Service during the war. My dad used to do a comic impersonation of Hitler, which the BBC broadcast to Germany on April Fool’s Day. It was hilarious stuff, crazy stuff, but just about realistic enough to be believable.

“My dad’s real name was Rudolph Muller, but he used the stage name Martin Miller. He started using it back in the day in Vienna, a long while before he came to Britain. After the war, he did a lot of theatre and film work, but he looked a bit like Einstein and he was often typecast because of that. He always seemed to be playing the part of a psychiatrist or a professor. But he did well in the end. He was in the original cast of ‘The Mousetrap’, the long-running West End murder mystery play. He was in the first 1,000 performances of it. He also did a lot of films and TV stuff. So he did OK. My dad and my mum both did OK.”

Martin Miller’s film credits included ’The Third Man’, ‘Peeping Tom’ and ‘The Pink Panther’, while his extensive TV work included appearances in ‘The Avengers’, ‘The Prisoner’ and the very first season of ‘Doctor Who’. His career was cut short by his untimely death in 1969, when Daniel was 18.

“It was a strange time,” says Daniel. “He was quite a bit older than my mum and it was very sudden. I would have loved to have got to know him better. I know about his career, because that’s well documented, but most of what I know about him comes from my mum. I mean, you don’t really engage that much with your parents when you’re a teenager, do you?”

Do you have any brothers or sisters?

“No, I’m an only child. Which is odd because I come from a big family. My father had something like 10 brothers and sisters. Some of them died in the war, in the concentration camps. My father’s eldest brother died in the First World War actually. My grandfather was married twice and effectively had two families, so there was a whole generation of siblings much older than my father. Of the ones who survived the war and the camps, some of them had no children, some of them only had one child. But I still have family who I’m in touch with and I’m close to, so that’s good.”

Do you have children yourself?

“No. No kids. Well, when I say I’ve no kids, I’ve got that lot up at Mute.”

So some of them act like kids, do they?

“Some of the artists do. No, that’s not fair. They are like kids, but in a different way. Children are very creative. Some of them feel like they’re kids because they have very child-like qualities in terms of the way they create, which I think is fantastic. And do they act like spoilt children sometimes? Yes, of course they do. It’s all part of the job.”

The conversation moves on. We talk about Mute’s publishing arm, Mute Song, whose signings include Underworld, Jóhann Jóhannsson and Max Richter. There are some surprises on the roster too, most notably Peter Green, one of Daniel’s 1960s blues heroes. We talk about his trip to North Korea with Laibach a couple of years ago and his new-ish hobby of street photography and his long friendship with Nick Cave. Daniel says he wanted to release the first Birthday Party album on Mute, but he was still running the label on his own back then and he didn’t feel he could do right by them, so Cave and his buddies went off to 4AD.

Before I know it, our time is running out. Daniel checks the clock on his phone a couple of times in as many minutes, but there are a few quick questions I want to get in before we end.

What do you think about the state of the music industry at the moment?

“Well, from our point of view as an independent label putting out pretty much non-commercial modern music, things are pretty good. Streaming has an impact, a constant impact, but it doesn’t affect us as much as it affects the much more mainstream pop labels. Physical sales are not doing too badly and the vinyl boom has obviously been a help. Running a record company has always been a bit of a struggle, but that’s OK. The important thing is that we can break even and put out the records we want to put out.”

Do you think the industry has found a new business model that works yet?

“It’s getting there. I mean, for a long while the labels were saying, ‘How do we stop this?’, not ‘How do we embrace this?’. That’s changed. Sync licensing is a big deal for us on both the record company side and the publishing side. Years ago, you’d get the occasional advert, but we do very well with TV shows now, especially with some of the darker shows on Netflix and Amazon. A lot of our music seems to fit well with those kind of things.”

Looking back over the years you’ve been running Mute, what was your biggest slice of luck?

“Seeing Depeche Mode supporting Fad Gadget at The Bridge House in Canning Town,” replies Daniel. “Frank Tovey and the guys went off to get some dinner and I stayed at the venue. I would normally have gone with them, but for some reason I didn’t that night. So I saw Depeche Mode play and that, of course, changed everything for Mute. I suppose I had to have an understanding of what I saw and heard, but there was no skill in being there, in being in the right place at the right time.”

You still have links with Depeche Mode, don’t you?

“I do. They’re obviously on Sony now, but I help out a bit with A&R every once in a while. I’m still very friendly with them.”

And what would you say was your biggest regret?

“I don’t regret any of the business decisions I’ve made, but I do have one A&R regret. We released a few film soundtracks on Mute in the early 1990s, but they all sold poorly and I kept thinking, ‘What are we doing this for?’. Just at that time, I was approached by Michael Nyman who offered me ‘The Piano’. He was really pushing me to do it, but I turned him down. I said, ‘Mike, I’ve had enough of doing film soundtracks’. I have to say that’s a regret because it’s an amazing piece of music and it’s also one of the most successful soundtrack albums of all time.”

Daniel has an important meeting with BMG this afternoon and he’s worried he’s going to be late. He makes a quick call to the Mute office and asks for someone to pick him up outside the restaurant and take him to the meeting. He then settles the bill and we wander outside, blinking as we come out into the late spring sunshine.

We stand on the pavement for a while, chatting mainly about football. He’s a Chelsea fan and he’s not very happy with how last season panned out. After a couple of minutes, he makes another phone call.

“Where are you? No, I’m outside the restaurant. No, it’s further down. Other side of the street. Hang on, I can see you now.”

Daniel pops his phone back into his pocket as a silver car draws up in front of us. “This is me,” he says, nodding and smiling and shaking my hand, before walking round to the passenger side. He’s a tall man and it takes him a few moments to clamber in and make himself comfortable in the seat. As he does so, I notice that the vehicle is quite old, quite rattly and very small. I think it might be a Ford Ka. I don’t know what sort of car I was expecting to turn up to take the boss of Mute Records to an important meeting, but it wasn’t anything like this one.

And with a cheery wave and some metallic clanking noises, the little silver car carrying a somewhat squashed Daniel Miller – forward thinker, futurist, charmer, not really a musician, not really a businessman, but definitely a colossal figure of both the electronic music scene and the recording industry in general – zips down the road and out of sight, leaving me to pick stray pieces of fish and clumps of sticky rice off my shirt. Flipping chopsticks.