Since 1981, In The Nursery’s cinematic soundscapes have evolved in fascinating ways, yet remained timeless. Their latest album is a deeply personal and beautifully orchestrated journey into their family history – and is perhaps the duo’s finest work to date

If the past is indeed a foreign country, then In The Nursery like to visit regularly. For the last four decades, they’ve made their own distinctive chiaroscuro darkwave with romantic overtones, offset since 1996 by their Optical Music Series, where they soundtrack some of the great movies of the silent era – ‘The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari’, ‘The Passion Of Joan Of Arc’, ‘Man With A Movie Camera’ and more.

While it might sound counterintuitive, In The Nursery’s Klive and Nigel Humberstone tend not to look back when it comes to their creativity, even if their inspiration is sometimes a century old. Their rousing symphonia is an innovative melange of sonic artefacts – library samples, timpani and live strings, often recorded with an old ribbon microphone, creating something uniquely ITN. They’ve been variously described as “martial industrial”, neoclassical or even, as Nigel says with a shudder, “gods of the bombastic”. But, all the while, In The Nursery have continued to do their thing, undeterred by the whims of fashion.

That being said, the Humberstone twins recently found themselves taking stock throughout the parenthesis of the pandemic. Circumstances forced them to look back and reassess who they were, especially following the death of their older brother Richard in 2019.

“Although those things take a while to catch up with you, you start reflecting on the fact that you are the remainders,” says Nigel. “We are the remnants of our family.”

Their 2017 album ‘1961’ – reissued last year – returns to the scene of their birth, paying tribute to Yuri Gagarin, ‘Solaris’ and the Ford Consul, among other 1961 relics. Klive and Nigel take delight in noticing things that others don’t. Like, for instance, 1961 being a strobogrammatic year – an irregular palindrome that is rotationally symmetrical. They say ‘1961’ was a very personal album, but their 2022 follow-up, ‘Humberstone’, delves even further into the people they are and where they come from.

Humberstone’ pays tribute to their antecedents. Stretching back across several centuries, it takes in war veterans, cavalrymen, gunsmiths, seamstresses, jewellers, a ploughman and their father, Arthur Humberstone, who died in 1999.

“Our dad was an animator,” says Klive via video call from Sheffield. “So we’ve got lots of ephemera stored in the studio. We’re slowly going through the archive.”

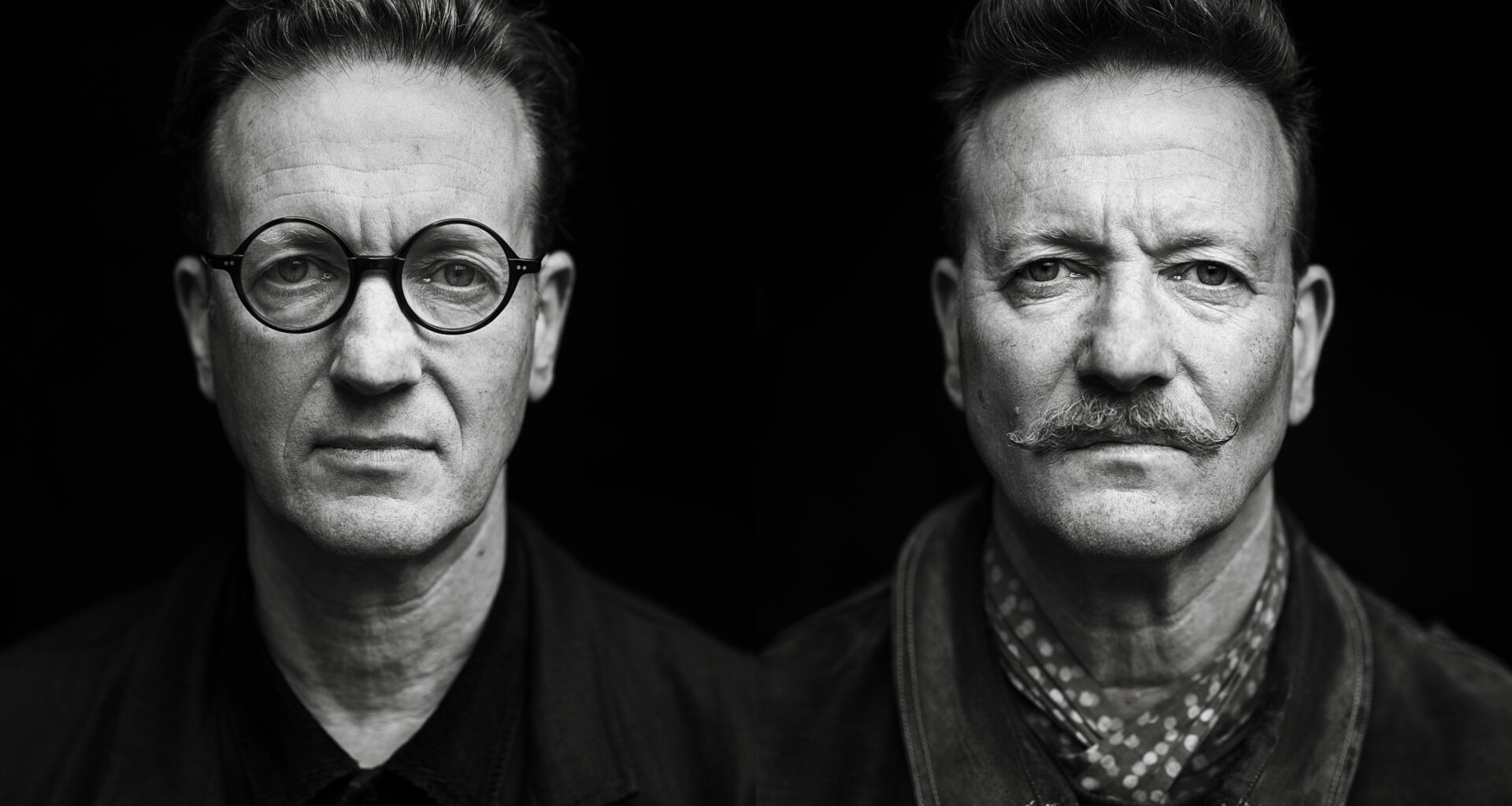

Nigel, his identical twin, is in another window, but in a separate Sheffield location. Klive’s moustache and Nigel’s glasses help me tell them apart, though they’re so similar that the recording software I’m using can’t differentiate between their voices.

They grew up in Cookham, a leafy Berkshire village on the outskirts of Maidenhead, where Arthur had his studio. Humberstone Senior worked on everything from The Beatles’ ‘Yellow Submarine’ to ‘Watership Down’ and the TV movie of ‘The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe’. These are very psychedelic animations, I say, whereas Cookham is perhaps the least psychedelic place on Earth.

“Yeah, he used to go up to London to work quite a lot in Portobello and Kensington,” says Klive. “He was one of the elders, I guess. During the swinging 60s, he would have probably been in his swinging 60s.”

Apparently, for the making of ‘Yellow Submarine’, just about anyone who drew professionally in the UK would have received the call, but for a work like ‘Watership Down’, their father would have been allowed to impose his own style on the project.

“We kept loads of rabbits and we had dogs at home,” says Nigel. “And at the very beginning, when they had the character sheets for the different rabbits, he took that on board and researched it. Those sheets then became the characters in the film, so it was fascinating to see.”

The pair lost their mother in 2012 and were hit hard by the death of their brother seven years later. Richard worked in publishing and design, and it was he who researched the Humberstone family tree, helping to uncover a cast of lost descendants and their stories.

Richard – or rather the child version of Richard – appears in ITN’s video for ‘Ektachrome (The Animator)’, the first track to be released from the new album. He is several years older than his twin brothers, who are both dressed as cowboys. The older Humberstone boy can be seen in the Super 8 montage being chased playfully across the garden as the sunlight drenches the camera lens, a happy and slightly uncanny moment captured from the mid-1960s. The images have been digitised from a large surplus of film canisters, a pile of aluminium you imagine they’re not quite finished with yet.

“Aside from being an animator, our dad was also an avid filmmaker,” says Klive. “When we were on holidays or out anywhere, he’d be there with his Super 8 camera.”

The idyllic video also features footage of their mother, sitting serenely on a coastal clifftop, with crisp, slinky bass accompanied by John Barry-like strings drenched in reverb. It conjures a mood that elicits memories in the viewer, even if they’re not our own.

“A lot of people were very pleased to see a Chopper,” says Nigel, laughing.

He’s referring to the iconic Raleigh bicycle from the 1970s that one of the twins – in his early teens – can be seen pedalling in the film. In the mid-70s, their dad would draw the curtains and show these films at family gatherings.

“He’d set up a film projector and play these movies he’d taken by the seaside, down by the river or us in the garden playing,” remembers Klive. “And he’d always set it to music he liked.”

Arthur’s personal preferences included ‘A Swingin’ Safari’ by Bert Kaempfert And His Orchestra and anything by Tammy Wynette. In the hands of the Humberstone twins, it becomes documentary material soundtracked by an imaginary library classic from the KPM All-Stars. If it appears to have a nostalgic sheen, then In The Nursery are not that interested. They’re more like historians – in this case, chronicling their own lineage and bringing it alive for a contemporary audience.

In The Nursery often convene with analogue ghosts, too. In 2006, they were asked to bring to sonic life the BFI DVD ‘The Electric Edwardians’. The piece chronicles a series of “local films for local people” shot by the Mitchell & Kenyon film company in the early part of the 20th century, showing working-class schoolkids mugging at the camera or workers leaving a factory in Sheffield. Those same players were then charged to watch themselves at a cinema extravaganza a few nights later.

At the time, the films were used to make a quick buck, but they’re now invaluable social records from a barely documented period, when nascent film equipment was rare and difficult to transport – if you could lay your hands on any in the first place. There’s something haunting about seeing children playing, full of vitality, yet knowing they probably died several generations ago.

“You look at these kids and think, ‘In 10 years’ time, the Great War will start and they may not get through it’,” says Nigel. “You see people walking with bowed legs, probably from rickets. You see how they dressed, how many wore hats. It’s amazing to look at, and it’s got great footage of Sheffield.”

“You see how people react to the camera, which is just stuck to the ground,” adds Klive. “A lot of them are standing still because they think it’s a normal camera and they’re having their photograph taken.”

That sense of the eerie is certainly present in the new work. The packaging for ‘Humberstone’ is as tactile and evocative as you might have hoped – a CD that feels more like a family heirloom, marked with an ITN insignia on the cover and featuring an old typewriter on the back. Each track is listed in the order the ideas came to the pair. So, for instance, ‘Ektachrome (The Animator)’ is listed as H43 and ‘Redpits (The Gardener)’ is H31.

“I started getting these ideas together and the best way to catalogue them was to say this is H7 or H8,” says Nigel. “You can see that many of the early ones weren’t developed.”

These numbers also correspond with photos from the archive, reproduced in the booklet accompanying the CD. For H43 – relating to the epic ‘Émigré (The Dressmaker)’ – there’s a sepia-toned shot of Arthur Humberstone as a young man holding his camera, while ‘H24 Mallards (The Storyteller)’ is duly linked to a silhouetted profile of their mother. The closing track, ‘H57b A Room At The End Of The Mind (The Jeweller)’, correlates with the picture of a dapper, handsome chap in a dinner jacket. The family resemblance is remarkable.

“It’s fascinating because there were gunmakers, and one was a jeweller,” says Nigel. “You discover the things they did and you get closer to your grandparents. What they did when you were growing up as a very small kid – you didn’t realise it at the time, but you sort of understand it now. It is quite comforting, and I think musically we’ve tried to capture that, although we didn’t think too hard about it. And we’re probably trying to think too hard about it now.”

With ‘Humberstone’, they’ve managed to reanimate forebears who were caught up in tragedies, extending an empathetic hand across time. The opening track, ‘H21 Émigré (The Dressmaker)’, is attached to a remarkable piece of family history.

“Our brother had highlighted that one of our past ancestors was on a immigrant ship going over to New Zealand,” continues Nigel. “And when we looked back into that it was an amazing story, where these wooden ships were sailing around South Africa, and then there was a fire on board. The whole ship goes down and you’ve got no supplies or lifeboats. Something like that was what you wanted to write music about.”

‘H47 Suvla Bay (The Cavalryman)’ concerns their great-uncle, Tom Squire, who was in the infamous Gallipoli campaign in the First World War. He had joined a yeomanry regiment known as the Rough Riders, though his training would be for nothing.

“He was part of the landing at Suvla Bay,” says Klive. “We’ve got copies of the letters he typed back to his mother and father, recounting what he did during those beach attacks in 1915. And it really does make your mouth fall open.”

“They got on boats, went to Cairo, went to Gallipoli,” expands Nigel. “And they did the beach landings and realised, ‘Oh, you don’t need horses for beach landings’. So they got stuck on foot and had to suffer untold horrors in these trenches, just waiting to be shot at by the Turks.”

The track was built on the sound of a Korg MS-20 detuning itself to the point where it breaks up and there’s no longer any sound coming from the machine. It was patched into MIDI with notation sent to a cellist, who accompanied the descending line, evoking the harrowing tones of modern warfare.

“I’m anti-war, big time,” adds Klive. “And you sort of realise that they did what they had to, sending typewritten letters back to their mum and dad, saying people you knew weren’t around anymore or wouldn’t be coming back. It’s very succinct.”

Sgt Thomas Arthur Squire survived Suvla Bay, but he wouldn’t make it out of the war alive. On 30 November 1917, he died from injuries sustained during the Battle of Jerusalem.

“Defending the Empire,” says Klive, with ironic disdain.

Does so much personal archival footage fortify memory, or do memories remain precisely because the footage exists? In the modern age, where everything is instantly documented with camera phones and social media, what will be the impact on the recall of modern generations? This is a question the Humberstone brothers ponder.

“It’s quite odd, isn’t it?” says Klive. “I’ve looked back on memories and wondered if they are actual events I’ve experienced or if I’m remembering a movie or footage of it.”

“That’s a really interesting point,” muses Nigel. “But having those measurable reminders is great. One of the tracks has a very small excerpt of an audio recording of our mum reading a bedtime story to us. Nowadays, you can just pop your phone on record and capture the moment. But a lot of people don’t have those things, so I feel quite privileged to have had that from our background. It certainly helped with the making of that track, which we built around the audio.”

Is it comforting to have all these mementoes?

“I guess it is, yeah,” says Klive. A Pinter-esque pause ensues. “It makes greater sense of the family and the past, and gives you more of a grasp of where you came from, of your ancestors and what they did. It brings things together.”

‘Humberstone’ is out now on ITN Corporation