The Human League, Cabaret Voltaire, Clock Dva, Vice Versa, and a whole lot more besides. What on earth was going on in Sheffield in the late 1970s? Was the electricity really better there? Six of the key players take us back to the early days of the Steel City’s pioneering electronic scene, with tales of groups like Musical Vomit, The Dead Daughters, The Studs and The Future…

Fired up by Kraftwerk and Kubrick, Bowie and Ballard, punk and disco and glam rock, a high-voltage wave of left-field electronic bands emerged from Sheffield in the second half of the 1970s. But how and why was the future sound of everywhere forged in Britain’s answer to post-industrial Detroit? Why not some larger city with an established music scene, like London or Manchester?

According to Richard H Kirk of industrial electro-punk pioneers Cabaret Voltaire, the Sheffield scene was shaped by its very remoteness from the national grid of pop culture. Boredom and bloody-mindedness make a powerful cocktail.

“There were very few clubs,” recalls Kirk. “Very little music apart from Tony Christie or whatever. So we decided to invent some. That was in 1972.”

Mark White from Vice Versa, the synth-bashing noiseniks that later evolved into sparkly 80s chart stars ABC, has similarly grim memories of the city’s barren pre-punk landscape.

“I’m sure that’s why Sheffield was a major producer of pop music,” he says. “There was fuck all else to do. It was about filling time, in the old-fashioned hobbyist sense. There might be one decent programme on TV at night worth tuning in for. So people started their own little bands.”

Martyn Ware, co-founder of The Human League and Heaven 17, claims the city’s steel-making industrial heritage is woven into its musical DNA. “You’d go to sleep at night and hear the drop forges hammering away like a metronome,” he says in Eve Wood’s excellent 2001 documentary, ‘Made In Sheffield’. “It was like a heartbeat for the whole city.”

Other Sheffield musicians cite the effect of dystopian modernist architecture, like the hulking concrete housing blocks that loom over the city’s hilly horizon.

“It was the spirit of the age,” says Mark White. “There was a certain glamour, the sense of the future was really exciting, yet we were actually experiencing it with our own eyes. There’s a big Brutalist housing estate in Sheffield called Park Hill. At the time, it was the largest one in Europe. I used to drive past it every day. I always felt it was actually incredibly epic and beautiful.”

“The place I particularly remember was Broomhall Flats,” says Adi Newton, the prime mover of electro-acoustic experimentalists Clock DVA. “I lived there for a brief while and I think Martyn Ware was there too at one point. It was very concrete, very Ballardian. That was the Sheffield way, even to the extent of demolishing some of the fantastic old Georgian buildings in the city centre to make way for office blocks and car parking. Everything had to be modern, it had to be new, but a lot of it was just shit.”

Such fanciful environmental factors may seem only tenuously linked to Sheffield’s sonic output. And yet, walking around the city today, the post-industrial structures certainly press more Ballardian buttons than in other British urban centres. Perhaps this explains the special love that Sheffield musicians developed for the future-yearning sci-fi romanticism of Kraftwerk, David Bowie, Roxy Music, Brian Eno, Giorgio Moroder, Donna Summer and other electric dreamers.

“Bowie and Roxy had been so big in Sheffield,” says The Human League singer Philip Oakey. “It’s sort of legendary that we were more Bowie and Roxy inclined, and even Deaf School inclined, than we were guitar inclined. Well, apart from the metal people, and there were a lot of metal bands in Sheffield as well. Our big metal band was Def Leppard and I still see them about. Joe Elliott’s a big Mick Ronson fan, for instance, and I love Mick Ronson.”

Martyn Ware claims youthful inspiration from more avant-garde composers like Iannis Xenakis, but also from broader literary and artistic influences, including Samuel Beckett, Alfred Jarry and the Surrealists. Adi Newton namechecks Beckett and Jarry too, as well as John Cage, Harry Partch and the likes of Jackson Pollock, Richard Hamilton and Man Ray.

“And Lou Reed’s ‘Metal Machine Music’, you can’t really overestimate how important that album was to people of our age,” says Ware. “It really made it clear to us that all bets were off. You could do what you wanted and it didn’t matter if it sounded like a mess. The fact that you were doing it was enough and that gave you the confidence to have a go.”

Sheffield’s long history of Labour-dominated municipal socialism is another important thread in this story. That was the principle behind Meatwhistle, the council-backed arts workshop which served as a creative springboard for working class kids with more ideas than money. Housed in a former grammar school on Holly Street, close to City Hall, Meatwhistle became the incubator for embryonic versions of The Human League, Clock DVA, Heaven 17 and more.

“It’s always been a fairly Labour city,” says Oakey. “I wonder how many groups came out of Meatwhistle, the theatre group that The Human League came out of? That was funded by the council. If you wanted to do that sort of thing, I think you could find outlets for it. They seemed to be trying to support people. We were all a bit lefty and a bit arty.”

Meatwhistle was founded in 1972 by Chris and Veronica Wilkinson, actors and dramatists who had previously worked at the Playhouse and the Crucible theatres. Drama was their key focus, but they also encouraged experimentation with film and music. Martyn Ware, Ian Craig Marsh, Adi Newton and Glenn Gregory all met there for the first time.

“It was like an anarchic youth club,” says Newton. “We used to hang out there for hours on end.”

“I’m eternally grateful to Chris and Veronica for coming up with this idea, because it changed my life,”

declares Ware. “Drama was a big part of it, but they also had an early video camera that we could use and some musical equipment. They just encouraged us to be creative. We started messing about with imaginary groups. We’d have an audience of around 20 or 30 within Meatwhistle, but we never used to perform to anybody outside.”

One group that eventually did escape the confines of Meatwhistle was Musical Vomit, a fluid outfit featuring Ian Craig Marsh and occasionally Ware, as well as Paul Bower, later of cult post-punk outfit 2.3. X-Ray Spex singer Poly Styrene witnessed one of their shows and retrospectively hailed Musical Vomit as the first ever punk band.

Another Meatwhistle creation was The Dead Daughters, which also involved Adi Newton. They existed just long enough to give a single performance at a friend’s birthday party. In the process, however, Ware, Marsh and Newton laid down the blueprint for The Future, the first incarnation of The Human League.

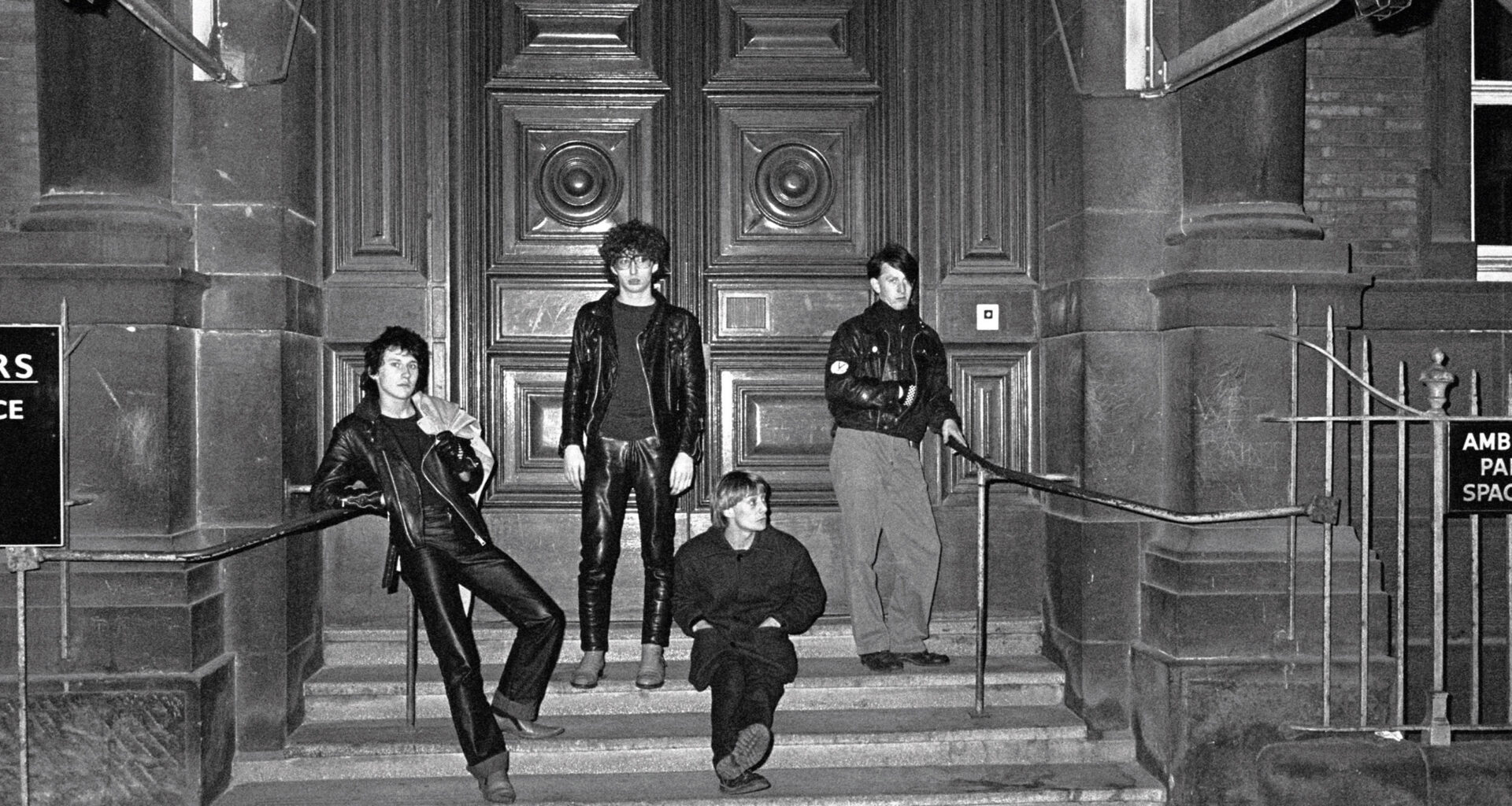

Collaborations between musicians was a big driving force behind Sheffield’s early electronic music boom. Most of the main players have worked together in various formations over the years, whether on stage or on record or both. Many emerged from the punk scene, which put them at odds with the local “townies”, who were still sporting flares and long hair. As in most provincial punk subcultures, these arty misfits bonded together for reasons of personal safety as much as musical solidarity.

“As a punk, you got aggro,” nods Mark White. “That was the vibe. You couldn’t walk through town, in case you came across a bunch of townies or teddy boys. It was very partisan.”

“When I think back, the punks were so few in number,” says Stephen Singleton, who partnered White in Vice Versa. ”You could practically name them all. And the people who were interested in that went on to form bands, but in Sheffield they didn’t form punk bands, they formed different types of bands.”

Sheffield did actually produce plenty of impressive noisy guitar outfits, including 2.3, The Extras, Artery, The Comsat Angels and I’m So Hollow. But noisy electronic music made with a punk attitude was much more prevalent, most likely due to the influence of local heroes Cabaret Voltaire. Stephen Mallinder, Richard Kirk and Chris Watson had presciently begun crafting their scouring industrial soundscapes way back in 1973.

“There was a Sheffield scene in the late 70s, but it basically revolved around Cabaret Voltaire,” says Kirk. “Not blowing my own trumpet, but we had this studio, Western Works, on West Street, where there were a lot of pubs. We got this studio space in 1977. There was this pub round the back, The Beehive, and a lot of people who followed us went in there. So at any one point, it was full of people in bands or wanting to be in bands.”

“I didn’t know the Cabs until I was in a group, I’d never heard of them,” says Philip Oakey. “But we were all in the same pubs on West Street. There were a few places where you’d find all the musicians together, like The Beehive. The university scene was very healthy too, with bands playing in Bar 1 and Bar 2”.

With their own studio, plus the accumulated kudos from John Peel radio sessions, positive music press interest and Joy Division support slots, it was natural that the Cabs would be adopted as role models by the city’s nascent electro-punk scene. Indeed, it was Richard Kirk who first introduced Martyn Ware to Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’ at a sweltering garden party in 1977. Ware was “transfixed” by the revolutionary rhythms of Düsseldorf’s funky pop professors. The future had arrived.

As 1977 rolled on, Ware, Marsh and Newton realised that The Future was a rather more serious proposition than The Dead Daughters. They’d built their first synthesisers themselves, following instructions in Practical Electronics magazine, while Newton used a Ferrograph reel-to-reel borrowed from Meatwhistle. But once Ware and Marsh started working as computer operators, they bought a Korg 700 on hire purchase. Ware also bought a Stylophone 350S, which was much bigger than the standard model and incorporated a photo sensor that triggered a wah-wah effect when you moved your hand in front of it.

With their equipment expanding, The Future moved into their own independent base in a disused factory on Devonshire Lane. It was here that they began working up demos of electronic sound collages, with Newton generating lyrics using a William Burroughs-style computerised cut-up technique that he christened CARLOS – Cyclic And Random Lyric Organisation System.

“We were each assigned a letter – A, B or C – and we had to think of a word or a phrase or a sentence when our letter came up,” he explains.

“It was a bit like Andy Warhol’s Factory,” says Ware. “That’s how we viewed it. We thought we were so cool because it was all post-industrial and we’d have parties in these horrible, filthy places. It all seemed very edgy and fun. This was our renaissance, our kind of flowering of understanding of the world with no limits.”

“We used the demos to arrange meetings with record companies in London, but they didn’t understand what we were about,” remembers Newton. “They didn’t know what to do with us or how to market us. We were too far ahead at the time.”

The Future were not alone, though. Not in Sheffield. Elsewhere in the city in 1977, Mark White and Stephen Singleton formed Vice Versa with a heavily electronic agenda.

“Rock ‘n’ roll,” sneers White. “I can never say that without an awful disparaging tone. It just seemed so old hat to be mucking about with guitars. Electronic music felt so revolutionary, more revolutionary than punk.”

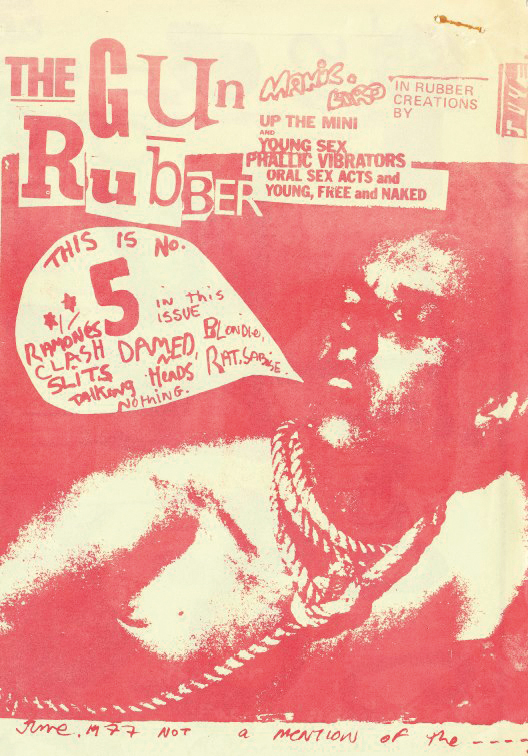

Helping to fuel Sheffield’s blossoming scene was a vibrant range of local fanzines, the first of which was Gun Rubber, edited by Paul Bower of 2.3 and with input from Adi Newton. It was printed on a hand-cranked stencil duplicating machine at Meatwhistle. A little later came Modern Drugs, which was created by future ABC frontman Martin Fry. The city also boasted a gradually increasing number of live music venues, most notably The Limit on West Street, as well as the bars at Sheffield University and the old art college in Psalter Lane.

Now part of Sheffield Hallam University, the art college hosted one of the most fabled nights in the city’s musical history when The Future joined forces with Cabaret Voltaire and Glenn Gregory, plus Bower and Haydn Boyes-Weston from 2.3, to perform as the support band for Manchester punk outfit The Drones.

“We were probably the only people in the world to have been part of a supergroup before we were really even part of a group,” quips Ware.

“I’d interviewed The Drones for Gun Rubber and I sort of cadged this support slot when I heard they were coming to play in Sheffield,” recalls Newton. “We decided what we were going to play, but I don’t think we had any rehearsals. We just got on the stage and did it.”

Under the name The Studs, the sprawling one-off collective played wilfully discordant cover versions of the ‘Doctor Who’ theme, The Kingsmen’s ‘Louie Louie’, Lou Reed’s ‘Vicious’, and The Stooges’ ‘Cock In My Pocket’. There was also a 10-minute improvised number entitled ‘The Drones Want To Come On Now’, which was mainly intended to annoy the headline band. The set climaxed with Boyes-Weston, who was working in a butcher’s shop during the day, tossing pig’s ears into the crowd. This Dadaist prank got him arrested.

“It was all part of the kind of conceptual art thing,” explains Ware. “It was pretty mad stuff.”

By 1978, the Sheffield scene’s avant-garde experiment was drawing to an end. Frustrated by the resoundingly non-commercial direction of The Future, Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh parted company with Adi Newton, who formed Clock DVA shortly afterwards. The Future then became The Human League, with Ware recruiting his former school classmate Philip Oakey as singer, followed by Philip Adrian Wright as visual director and auxiliary synth player.

“The Future didn’t last very long, which was a bit ironic,” laughs Newton. “I think it was only about six months.”

To the guys in Vice Versa, who were slightly younger, The Human League and Cabaret Voltaire and Clock DVA seemed dauntingly grown-up.

“We were boys, they were men,” says Mark White. “They had proper jobs, they could grow beards. They could afford these really expensive synths, which we were just in awe of. What blew my mind was how perfectly formed they were. We had just started to mess around with second-hand synthesisers and rhythm generators, but they had obviously been developing this in secret for years. It just sounded like it had come out of the future.”

White recalls being shocked when Oakey informed him that he wanted The Human League to be like ABBA. But the singer has never had any qualms about his grand pop ambitions.

“We loved Genesis and Van Der Graaf Generator when we were at school, but we always liked pop music too,” says Oakey. “When Martyn told me that he liked Slade, it was like slapping me in the face! You didn’t admit you liked chart bands if you liked prog. But we did like pop. At the same time as hoping we would be like Can or Neu!, we also sneakily wanted to have hits.”

As the 1980s dawned, many of the first wave of Sheffield’s electronic artists were undergoing transformations.

The Human League had signed to Virgin Records and would soon turn their “electronic ABBA” fantasy into chart-topping reality. Ware and Marsh began work on their polished breakaway group Heaven 17, just as White and Singleton were shelving Vice Versa to rebrand themselves as suave soul-pop dandies ABC. Even the relentlessly abrasive Cabaret Voltaire and the tirelessly innovative Clock DVA were both on course for brief commercial phases.

But while all these pioneering bands would trade their underground synth-punk roots for varying degrees of mainstream success in the new decade, their legacies remained secure, their shared histories woven into Sheffield’s musical DNA. They will always be together in electric dreams.