“Lester Bangs told us that when Kraftwerk were in New York, they were in his apartment and he said, ‘This has just come out, now hear this!’. They were so blown away they took Lester’s copy… they just took his record!” – Martin Rev

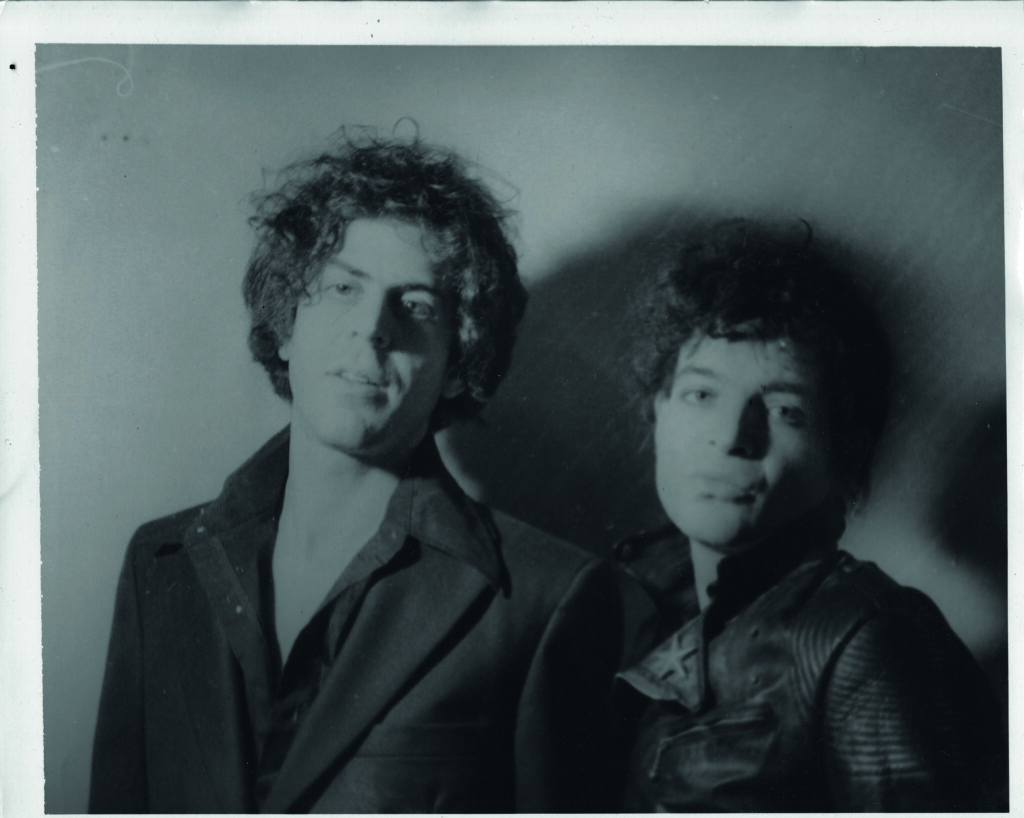

Suicide ‘Suicide’

Suicide were New York’s outsiders in 1978, having walked their super-voltage high wire for most of the decade before recording their eponymous debut album in 1977. While contemporaries from the mid-70s CBGB’s uprising such as Blondie and Talking Heads went on to win mass market acclaim, Alan Vega and Martin Rev remained vilified and usually abused when they played their home city, simply because they didn’t use guitars or drums.

‘Suicide’ was released in the US on 28 December 1977, the title daubed in blood on its cover. Few other groups at that time set out to skewer America’s ruined, bewildered, post-Vietnam psyche, and then hold it up to show the squalor, paranoia and quest for oblivion now infesting the country, especially in its ostracised heart of darkness, New York City.

Dirty, wild and beautiful, it was Alan Vega and Marty Rev’s monolith for the future, to appreciate what the present could not. As Rev says, “With us, most people said, ‘If this is the future, we don’t want it’.”

Suicide’s two-man revolution came through Vega taking Iggy Pop’s confrontational mayhem to fearless extremes, while Rev evolved the duo’s sound from his jazz-centric keyboard incantations. Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ subliminally spiked the first Suicide album with its electronic drum patterns.

“To me, ‘I Feel Love’ was the first time you had the sense of hearing a rhythm machine playing underneath a song,” says Rev. “There was a connection there for me; not that I wanted to emulate it, but I definitely got ideas from it. That was the beginning of a new sensibility in terms of electronics.”

But while New York discos such as Larry Levan’s pivotal Paradise Garage – the city’s hippest, most groundbreaking nightclub in 1978 – provided an open-minded and experimental social environment in which electronic masterpieces could cause ecstatic havoc, Suicide encountered relentless hostility in the rock world with their idiosyncratic approach to instrumentation and performance ethics.

Finally clinching a deal with former New York Dolls manager Marty Thau’s new Red Star label, ‘Suicide’ was recorded at Ultima Studios, upstate in the town of Blauvelt. “In the middle of nowheresville”, as Alan Vega described it. Producing was Craig Leon, who had steered debut albums by the Ramones and Blondie. Suicide started by setting up Rev’s Farfisa, Seeburg Rhythm Prince and distortion boxes, then hooking in a transistor radio.

“Marty Rev had this whole Rube Goldberg [the American version of Heath Robinson] bunch of stuff he’d put together, with the drum machine and all these other things,” recalls Leon. “There were no sophisticated synths or anything, it was just whatever he found!”

Max’s Kansas City manager Peter Crowley, one of the band’s earliest champions, still marvels at their set-up.

“They didn’t have any money, so Marty had a primitive drum machine, an old Farfisa keyboard with broken keys, and then a bunch of Electro-Harmonix guitar distortion devices that he plugged in series between the keyboard and the amplifier in order to get this really raunchy sound.”

The unique combination of cheap, patched-up components that made up Rev’s “Instrument” (as it’s credited on the record sleeve) played a major part in the album’s alien, radioactive sound.

“We just set up and played our set,” remembers Rev. “We’d been playing everything on the album live for so long, the songs had all developed themselves. After running through the set a few times, we cut the album in the time it took to record the songs, like 30 minutes. We cut everything live.”

“We ran through their set several times, because the way that it was recorded was the way they were set up,” says Craig Leon. “It was all coming out of a couple of outputs. There’d be a straight signal, then an amp signal, and then it went through these radio electronics and things. Basically, I put out a big mono signal, and I got what Marty was playing, and that was it. Then there was Alan. When I told him he was going to get these extreme loopy Elvis things, and these kind of repeat delays from Jamaican records, he was very much into it.”

Leon had thought very carefully about the best way to present Suicide’s senses-blasting live act.

“I knew what they’d done live and how unique they were, so this record really had to do them justice,” he says. “It couldn’t just be a blank version of what they did live so I thought, ‘Let’s go to the other extreme in the effects and what we do with the sound’. I thought the right thing would be to use a lot of effects from all the different kinds of music that was influencing them. Everything you hear on the record was printed live as it was going down. None of those effects are after-effects. It was like a dub mix.”

Leon says everything Rev was doing was going out through his guitar amp, which was miked as the original source sound.

“I said, ‘Let’s take off all your effects and we’ll put ’em on from here. Let’s try and record everything straight and clean, without the boxes, right into the board’. If you went back to the original tape somehow, you would get a very dry version of what they did live without all those effects. If you just put up the two tracks of Marty and the one track of Alan, you’d get what they play live with no enhancement. They had their live set pretty much down, so I did not say, like I did on a lot of other records, ‘How about doing this here?’. It was strictly interpretative.”

“Craig said to take off all my effects and play it straight,” concurs Rev. “I agreed to try it and see how it sounded. At the time, I was playing a Farfisa organ and it was a much thicker sound anyway. I was using a little AM-FM radio, which I could turn on and play as an instrument, and I used that live sometimes. Everything else was going directly into the board, which we had never done before. We were always going through an amp. I did very little overdubbing, maybe just a spot here and there, so the record was one-two-three- done. After that, it was all mixing.”

Suicide’s first album was created for a minuscule $4,000 in an atmosphere of cathartic intensity, stoned experimentation, and often under the kind of DIY circumstances which might have floored other bands.

“‘Suicide’ was and is a very moving, haunting, and genuinely groundbreaking masterpiece,” says Jim Sclavunos, once central to New York’s crucial no wave scene as a member of Teenage Jesus & The Jerks, now the drummer with Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds. “Even at the time, it instantly came across as an enduring classic. It never fails to transport me back to the visceral thrill of when I first saw Suicide perform.”

Vega and Rev were euphoric to see their album in the stores. As Vega told me in 2015, “Marty said, ‘You’re not gonna believe this, but the record’s in this store!’. I went down just to see it in there, sitting next to Bob Dylan. I was like, ‘Holy shit!’.”

Predictably, the reviews were derisory, including one by Robert Christgau, The Village Voice’s self-appointed “Dean of Rock Critics”, who gave ‘Suicide’ a C plus.

“He hated Suicide and referred to them as the Two Stooges,” says Red Star boss Marty Thau, who expected the poor reception. “I thought that was actually very funny, but Christgau was damn serious. He thought he was tres cool but, in most 70s Bowery circles, he was viewed as a hippie remnant from the days of groups like Moby Grape.”

Lester Bangs, on the other hand, who wrote for the Voice and the Soho Weekly News after moving to New York, was Suicide’s loudest supporter. “Suicide stands at the nexus where bubblegum music, Iggy Pop, Kraftwerk electronics, Eno futurism, New York street jive, and primal scream vocalisations all somehow magically mesh,” he proclaimed in the Soho Weekly News.

Bangs even played their album to a visiting Kraftwerk, who “understood immediately, and practically strong-armed me into giving them copies of the record to take back to Germany”.

“Lester Bangs told us that when Kraftwerk were in New York, they were in his apartment and he said, ‘This has just come out, now hear this!’,” affirms Rev. “Apparently, they were so blown away, they took Lester’s copy. It hit them so potently, they just took his record!”

Alan Vega, meanwhile, loved to tell the story he heard about the motorist who went apopleptic when ‘Frankie Teardrop’, the intense 10-minute track that dominated the second side of the LP, came on the radio.

“‘Frankie’ came on and the scream almost made him crash. He hated it, man. He took the radio out of his car and threw it out of his window, then drove his car over it to smash it. But that wasn’t enough. He put the car in reverse and went back over it the other way to make sure it was really fucking killed!”

“We were just singing the new blues, and the blues scares people,” reasons Rev.

Suicide’ came out in the UK in July 1978, seven months after its US release, as a result of Marty Thau signing a UK deal for Red Star with Bronze Records. Bronze A&R man Howard Thompson had been vey impressed by the album when it arrived in his mail in early 1978.

“I had a friend in Rochester, New York, a DJ on a radio station,” says Thompson. “I would send him punk singles and he would be the first person in America to play these things. In return, he would send me American punk rock – Blondie, the Ramones, Talking Heads. One day, I’m sitting in my office at Bronze Records, the last label anybody would ever go to to get signed. A 12-inch envelope turned up containing Suicide’s album. I’d never heard anything like it before. Every song blew my mind, but I think I was the only person that wanted to release the record in Europe.”

The UK press reaction to ‘Suicide’ showed greater awareness than in their home country, the most incisive review appearing in Melody Maker by Richard Williams. It was enough to clinch a European tour for the band, supporting first Elvis Costello and then The Clash, to much-documented overall abject hostility.

“Some say that Suicide were the ultimate punks because even the punks hated them,” notes Thompson. “But the truth of the matter is that Suicide redefined punk rock with a sound that was more disturbing and threatening than anything London’s radical bands had ever heard. And that just didn’t sit well with them.”

After the tour, Suicide returned to a changing New York – bruised, bloodied, but defiantly unbowed – and found themselves hailed as pioneers of the burgeoning no wave movement. Finally, they could make as much noise as they wanted, safe in the knowledge that someone on the next block was probably trying to make something noisier.

This stark new music, forged in the broken tooth landscape of Alphabet City, now ignited one of the briefest supernovas New York’s musical evolution has ever witnessed, although the post-punk shockwaves it unleashed can still be felt today. This was the real Year Zero, bent on obliterating rock structures while embracing extreme DIY strategies, along with broader musical forms often disdained by punk, such as free jazz, funk and even disco. Nothing was sacred, everything was permitted and, of course, it wouldn’t last for long.

‘Suicide’ was released by Red Star in December 1977 in the US and in July 1978 in the UK