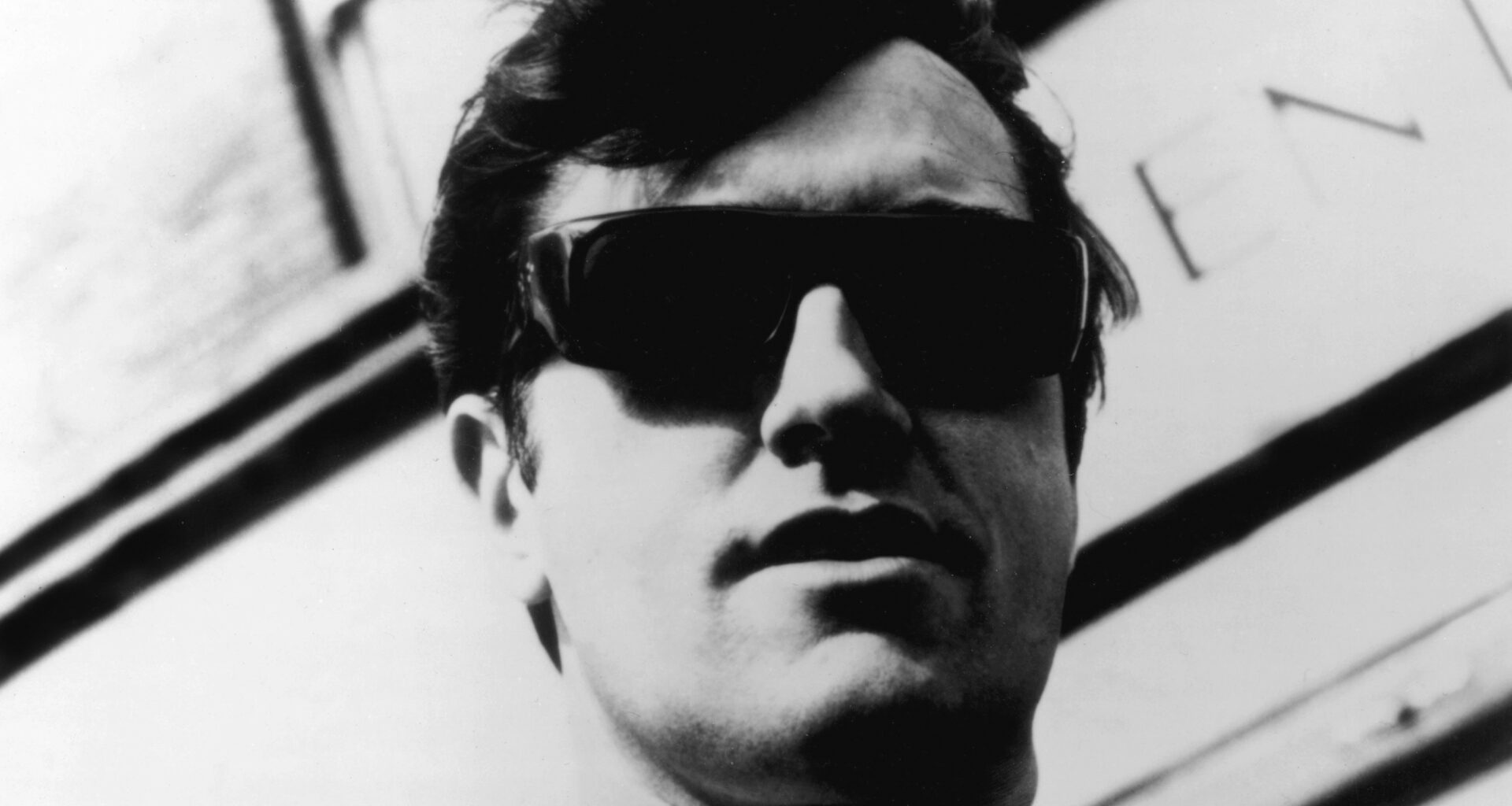

The tragic tale of the original pop Svengali would be fantastic enough even without the black magic, gangland threats and a pill-popping climax of paranoia, rapidly declining fortunes and murder… through a series of interviews, conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many with collaborators, artists and assistants who have since died, we tell the incredible tale of Joe Meek

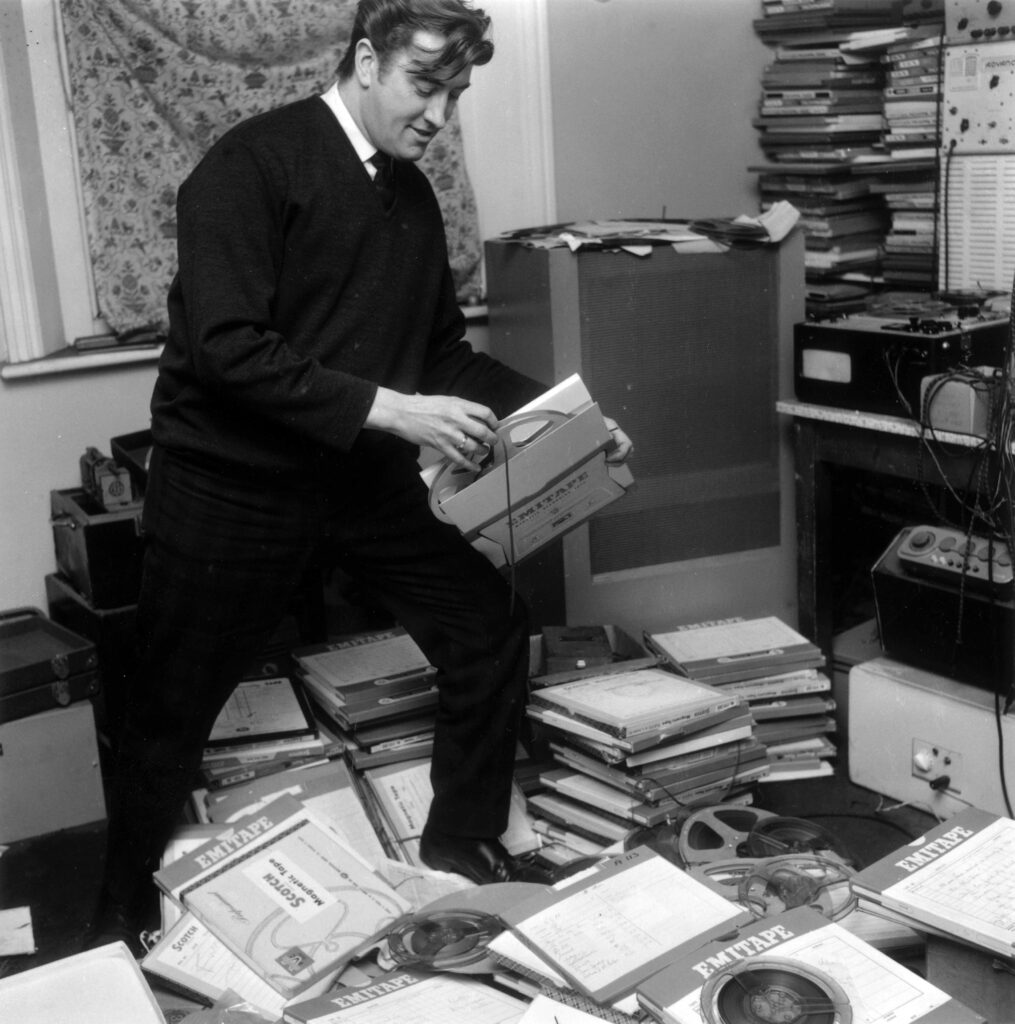

Between 1956 and 1967, when his creative whirlwind came to a murderous end, Joe Meek released over 300 records. Most of them were written, recorded, mangled, topped and tailed in his flat, a few damp and dark rooms above a leather goods shop on north London’s Holloway Road. Those releases are just the tip of an iceberg, with that toll amounting to less than a quarter of the songs he recorded before, on 3 February 1967, he took a shotgun and killed his long-suffering landlady. The murder makes a macabre soap opera of Meek’s story. It’s the stuff of sensational tabloid headlines, which at the time is exactly what they were.

Meek was a visionary genius dubbed “The Ed Wood of lo-fi” by writer Irwin Chusid. His crazy life, a hazy, pill-popping, paranoid horror comic, often obscures his pioneering work. When you hear the insane B-sides, freakbeat gems and a fearlessly individual approach that gave us an enduringly peerless suite of low-tech sci-fi mania, it’s easy to see him as an idiot savant of sound. Indeed, the now revered ‘I Hear A New World’, described by Meek as “an outer space stereo music fantasy”, was so far out there it was deemed unsuitable for release on its completion in May 1960.

With its fizzling shorted wire sounds, endlessly echoed primitive keyboards, miked-up milk bottles banged with spoons, and sleeve notes detailing a heartfelt belief in little green men on the moon, the concept album has only been truly acknowledged as a Spector-meets-Stockhausen landmark recording in the history of British electronic music. Vengeful and frustrated by being marginalised in his day as a barely credible loon, Meek didn’t live to hear the mocking laughter of the “rotten pigs” and “unbelievers”, who plagued him in his day, peter out.

Joe Meek created some of the strangest and most wonderful sonic experiments ever to gatecrash the hit parade. Known at one stage as “the British Phil Spector”, Meek, a self-styled auteur, who in the mid-1950s almost single-handedly invented the idea of independence in pop by selling his finished products to the major labels, was the creator of some of the strangest records ever made.

‘I Hear A New World’ was his defining statement, and sold in the low hundreds on its limited release in 1960. It is now acknowledged as a pioneering piece of eccentric electronic sound. These days, Meek sits alongside Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire in the iconography of British experimentation – a visceral, makeshift and often comic extension of it.

There’s a school of thought that The Beatles invented the future with ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’. Joe Meek was already light years away, while the Fab Four were still thinking about asking George Martin if it was OK to turn it up a bit. Twanged rulers, coins dropped in buckets and footsteps on the stairs were recorded and manipulated by home-made processors, then strangulated into something stranger. The synthetic sheets of sound that eventually obliterate four beat boys going through the motions on The Syndicats’ ‘Crawdaddy Simone’ seem like some terrifying weather system, and are hard to understand as the part of the prevailing sound of 1965.

Ken Pitt, who went on to manage David Bowie for a time, knew Meek well via the artists he looked after who recorded with him. Pitt, who died in February 2019 aged 96, was visibly relieved to be discussing anything but Bowie when I spoke to him at his home in Hertfordshire in 2000. He considered Meek to be the equal of Bowie in the story of British pop music.

“Everything he did in that tiny little studio was an act of faith in something,” he said of Meek’s intensity when he was at the controls. “Music was his entire life”.

“He found it impossible to think or talk about anything else,” said songwriter and collaborator, Geoff Goddard, who I interviewed in late 1999 at the University Of Reading where he worked, despite a few years earlier being “completely surprised” by a significant windfall following Marc Almond’s hit cover version of his 1961 Meek collaboration, ‘Johnny Remember Me’. Goddard died in May 2000, just a few months after we’d met, aged 62. He talked reluctantly about how Meek was nasty and unkind to him, on numerous occasions.

“He had quite a temper,” he said. “You had to negotiate that and the things he’d throw at you… screwdrivers, tape reel, anything he could find.”

It was clear the almost deafening din of the post-service student dining hall where we chatted was of no consequence to a man who lived to tell the tale of feedback, flying tape machines and overwhelming chaos at Holloway Road. “He was quite a character,” said Goddard as he stared into the distance behind me.

While the titles may have long evaded you, there are few unable to recall an encounter with the hysterical strains of ‘Johnny Remember Me’, the hard-faced punch of ‘Just Like Eddie’, or the infernal racket that is ‘Have I The Right’. The breathless rush of ‘Telstar’, the best-selling instrumental of all time, can’t even be spoiled by the fact that it was Margaret Thatcher’s favourite record.

Meek’s bridge-burning self-belief made him edgy, abrasive and frequently destructive. This seemed to impact significantly on his mental health. He hardly left his studio, and the hundreds of hours of taped experiments discovered after his death are a testament to this. There are tales aplenty of tape machines aimed at errant musicians (a young Tom Jones was almost seriously maimed in this manner), a temper that was never far from ignition, and delicious stories like the one about him sending a youthful Rod Stewart packing from an audition with a ripely executed raspberry. He would let anyone who cared to listen know that, “those bloody Beatles” were nothing more than “matchbox music” that wouldn’t last.

It’s easy to laugh at Joe Meek, but pop music owes him for insisting, as he did, that noise and discord had a place among the harmonies. His selfishly audacious genius makes him impossible to ignore.

“He felt that the sound was as important as the song,” said Goddard. “And I think he was one of the very first people in pop music to think that way. Today people take the creative input of the record producer for granted. Joe Meek did so much to pave the way for that.”

Robert George Meek was born four days late on 5 April 1929 in the Gloucestershire market town of Newent, a location that gave him a cider-curdling West Country accent preserved in 1960s radio interviews, where he talks of “delayin’ the echo”.

With a fascination for old radios and record players, he would take the backs off them and, with the help of a Practical Wireless subscription, he began building his own electrical gadgets. His talents made him popular. He would rig up speakers in the trees so the cherry pickers could listen to the radio as they worked and, as a budding DJ, he would travel the area with his own mobile set-up, playing dances for pennies. Meek joined the RAF as a radar technician and would spend his free time borrowing kit to build elaborate radios and tape machines. With his own acetate cutting lathe, he began recording small-time singers before he even made it to London.

With his talents unschooled but obvious, he moved to The Smoke in 1953 and was taken on by IBC Studios, where he learned the ropes as a recording engineer. Regardless of whether he was asked or not, Meek would try and stamp his sonic style (the result of all those Newent bedroom experiments) on the artists he worked with. He recorded Frankie Vaughan’s ‘Green Door’, notching up the echo effects while nobody was watching. On the trad jazz of Humphrey Lyttelton’s ‘Bad Penny Blues’, he messed with the microphones so the bassline was distorted, while the brushed drums sizzled startlingly, like frying bacon. Lyttelton was away while Meek mixed the track. He returned to find it finished and had to admit that, while he would never have approved it, it was quite a result.

Although by Meek’s own later standards, and the techniques we have now come to take for granted, like taking the front skins off bass drums and moving microphones to the exact source of the sound, his early experiments can seem tame. But in the days of studios ruled by lab-coated technicians, who frowned on any experimentation and broke for lunch at exactly 12.30pm, Meek was putting into practice a sonic sea change that would reverberate down the years. Before George Martin had even met The Beatles, and before drugs and artist input on recordings became the norm, these were the roots of a revolution. ‘Bad Penny Blues’ made the UK Top 20 in 1956 and the word, at least in certain circles in London, was out. Joe Meek was beginning to make a name for himself.

Meek started writing his own songs. He would vomit them out in a tone-deaf wail, borrowing freely from everywhere. He set up what can now be regarded as Britain’s first home studio in the bedroom of the Notting Hill flat he shared with his partner Lionel Howard at 20 Arundel Gardens. He took a job at jazz producer Denis Preston’s Lansdowne Studios, where he struck up a friendship with engineer Adrian Kerridge who, until his death in October 2016, defended Meek’s claim to the ultimate innovator’s crown in British pop production.

“Joe was unquestionably where it all began,” Kerridge, himself a respected elder statesman of the backroom, told me when I spoke to him in December 1999. “He had no rivals then. He was naturally talented and quite simply a pioneer in those dark and distant days. I believe he stayed ahead of his time in so many ways, up until his death. In his last days, he wasn’t scoring the hits quite as often, but the records he did manage to get out show a man still forging ahead with his own uniquely personal agenda.

“He just had such a taste for work, he didn’t ever stop. It was as if he knew he had a limited amount of time to make his mark. He used to take the slimming pill Preludin, constantly, and that kept him going. He had me up the wall in his endless search for something new. He was willing to try anything. I was a bit more trained than he was, so he would ask me to help him out with his ideas. He once asked me for a half out of phase lead. I told him there was no such thing and it wouldn’t work. But I had to make one anyway, just to prove it.”

Kerridge recalled that Meek would always take the backs off pieces of valuable equipment to tinker with them.

“He was never happy with what he had,” said Kerridge. “He was always dreaming up other ways of doing things. To be honest, the technology didn’t yet exist for some of the things he wanted to do. He had the boffins at EMI Hayes design a mixing desk that just confused them. They had never heard of the kind of equalisation he demanded. But they made it anyway and it sounded amazing.”

Apart from an obsession with sound, Kerridge remembered few conversations that revealed the man, despite the many hours they spent working together. Meek didn’t suffer fools and, because he was quite openly gay, Kerridge believed he became an increasingly isolated figure.

“I never had any problems with his lifestyle, but it’s hard to imagine now just what a taboo subject his homosexuality was back then. People judged him because of it, and he reacted by hating them. It was hard for him to fit in.”

Having lined up his own recordings during downtime at Lansdowne, Meek formed his own Triumph label in 1960 and released a few non-hits. Aside from a Buddy Holly-esque vignette called ‘Angela Jones’ by Michael Cox that made the Top Ten, they are best forgotten.

The only Triumph recording truly worthy of the name was the ‘I Hear A New World’ EP, which sold in such minuscule quantities that the projected part two bit the dust before it was even pressed. At his tiny Notting Hill flat and stealing hours at Lansdowne, Meek created groundbreaking soundtracks for astral travel via your Dansette, which were marketed as “stereo test discs”. They broke the sound barrier without making a dent in their day. Speeding up and effecting live band takes from the studio then layering them with echo and delay, he would add more icing to the cake than was wise. Sound effects like scraped combs, bubbles being blown in water, smashed glass, broken clockwork toys, radio interference, tapes being played backwards and toilets being flushed can be made out beyond the obsessive manipulation.

Drummer Dave Golding was part of The Blue Men group who were credited as artists on the ‘New World’ sessions.

“At the time we didn’t know what he was trying to achieve,” said Golding when I spoke to him in July 1999. “He wasn’t talking about space when we recorded some of those tracks. He was going on about lighthouses and lights across the sea, which makes some sense when you hear the record and forget about the titles.”

Golding recalled the sessions as fraught, late-night affairs, either at the flat or at Lansdowne Studios with Meek attaching knives and forks to his bass drum pedal and insisting he played with pennies spread across the skins. On hearing this record 60 years later, you can only wonder that Meek is the other, lost Aphex Twin, born before his time. Charles Ward, whose Thunderbolts record ‘Lost Planet’ is another example of Meek’s outer space obsession, believes he was really a child of the times.

“‘Destination Moon’ was the film of the 50s,” he explained. “In Hollywood, they were throwing dustbins up in the air at night and filming them as UFOs. There was plenty of that stuff around, and Joe was exposed to as much of it as anyone else.”

The genius of ‘I Hear A New World’ is tempered by comic tunes and further warped by Meek’s twisted sense of a pop world he desperately wanted to be part of. Aside from the heavily layered effects, these made up the bulk of the record’s musical substance. The sleeve notes, apparently written by Meek, show a man innocently obsessed with aliens, The Space Race and Sputnik flights into the beyond.

“Owned and built by the Dribcots, it is shaped like an egg” wrote Meek about ‘Dribcots Space Boat’ with barely contained enthusiasm. ‘Entry Of The Globbots’ is “the sound of happy, jolly little beings. As they parade before us, you can almost see their cheeky blue faces”.

It’s believed that only 100 copies of the record were originally pressed. There wasn’t much call for fledgling electronica in 1960. But with ‘I Hear A New World’, Meek had revealed the template for his way of thinking. This was his particular way of hearing, with all his secret sounds out on display. It was a statement of intent.

“Looking back, it’s clear that Joe did have a plan for the record,” said Golding. “It was only when ‘Telstar’ came out three years later that it all began to make sense to me.”

Unable to tolerate working with others, and with bills piling up (a testament to his disorganisation), Meek alsohad an ego the size of a house to maintain. He teamed up with a mysterious benefactor called Major Banks who, transfixed by his echo tricks while watching him play, bankrolled Meek’s dreams, buying half the shares in Triumph and so allowing him to set up his own studio.

This would be a castle where no one could question his sovereignty for fear of having a rack of compressors thrown at them, or being shown the door by one of a stream of assistants like Terry O’Neill and Patrick Pink, people who bore the brunt of an artistic temper frayed by slimming pills and growing paranoia.

With equipment borrowed, stolen and made from scratch, the rooms above Mr and Mrs Shenton’s leather goods shop at 304 Holloway Road were secured. With three forbidding flights of stairs for budding pop performers to drag their instruments up, it was not ideal. Sessions there were constantly held up while the heavy lorries that made their way up and down the main drag passed by. Together with the Major, Meek formed RGM Sound, utilising his initials while massaging his ego. Dave Adams, one of his growing stable of singers, was a dab hand with a saw, and kitted the place out with the surfaces to pile up the machines. It’s doubtful Mrs Shenton had a chance to note that her tenant had originated Britain’s first professional independent studio.

At a time when EMI and a handful of other studios built a fence around the status quo, Joe Meek was shadowing the tape-splicing, musique concrète experiments of more academic pioneers like Pierre Henry. The dots have been joined in recent years, but back then Meek seemed alone. Like Picasso walking into a stationery shop with ‘Guernica’ under his arm only to be told that it might not come out that well in a photocopy, Meek had to face engineers telling him “it’s just too distorted”. The record companies and their cutting engineers even refused to master some of his recordings, saying they would damage domestic speakers.

“He would say, ‘The rotten pigs, they should just bloody do as I say’,” recalled Kerridge. “‘I know what I’m doing’, he would say.”

It may all have ended as a joke without a punchline, a masterplan foiled, were it not for the arrival of a strange boy from Reading with a Berkshire accent to match Meek’s for comic value, an interest in spiritualism and a musical talent of its time. Meek met Geoff Goddard at an audition arranged by a publisher, and listened intently before solemnly declaring, “I shall call you Hollywood”. The title bestowed, Goddard wasn’t happy until he had secured the prefix Anton.

“We hit it off straight away,” said Goddard. “I sensed a kindred spirit. We were on the same wavelength.”

Anton Hollywood’s career was, however, short-lived, as Goddard’s effortless way with the all-conquering catchy tune quickly made itself known. Meek was looking for a song for the TV actor John Leyton, who was on the make in the pop scene like so many others who saw a second wage to be snatched from the hands of the emerging teenage market.

Goddard knocked up ‘Johnny Remember Me’ in “10 minutes”. He could not have known that this breathlessly camp classic, chock full of orchestral flourishes and windswept drama would be the canvas for the most famous session at Holloway Road.

With microphones attached to the banisters with bicycle clips, there was a string section on the stairs, singers in the bathroom and The Outlaws (featuring Richie Blackmore, later of Deep Purple) cramped in the front room. With Meek in the bedroom, his feet lost in a carpet of reel to reel tape and tangled wires like some primitive scientist of sound, he was twisting and tweaking his way to pop perfection. With compressors and limiters glowing hot and his Lyrec and TR51 tape machines criss-crossing takes, he was working overtime to make a mockery of his lab-coated peers, who were more worried about their overtime payments and the blasted meters going in the red. The Outlaws’ Chas Hodges (of Chas & Dave fame, who died in September 2018) played bass on the track.

“I could hear a girl singing, but I didn’t know where she was,” recalled Hodges, backstage after a Cockney knees-up with partner Dave Peacock in February 2000. “I remember thinking she must have been in the bathroom. I heard Joe saying, ‘Oh, the violins have arrived’, but I never saw them. They were on another floor in the flat.”

It was clear then that, though Meek had little respect for musicians who worked with him, he remembered his time at Holloway Road fondly.

“It took so many takes to get it right that he played until his fingers bled,” laughed Goddard as he remembered “the boy on the rhythm guitar”. “There were cables all over the place and people squashed in corners. I remember some old boy trying to find enough space to drag the bow across his violin in the corner.”

‘Johnny Remember Me’ was released in July 1961 and made Number One the UK charts, staying there for 15 weeks. The industry itself was in its teens and too young to understand. Critics mocked that Meek made records “in the bathroom”. “It sounds as if he is singing down a very deep hole” raged one critic about the Meek masterpiece. Arranger Martin Slavin kicked against the success of ‘Johnny’ in his Melody Maker column: “A recording studio is the place to record. They are there for that specific purpose and they have the best technicians in their employ.”

Meek couldn’t resist the opportunity to reply in print…

“Fair enough, my studio started out as a large bedroom, but it is now a first-class studio in which I have made many hit records. I would be a fool to listen to an arranger with a bee in his bonnet. I make records to entertain the public, not square connoisseurs who just don’t know”.

Released in 1961, The Moontrekkers’ genuinely unhinged ‘Night Of The Vampire’ was prefaced with wind, rain, thunderstorms, and featured a guitar so eerily effected it made the drums, sounding like large boulders rolled down a mountainside, seem comparatively unremarkable. It was banned by the BBC as being “unsuitable for people of a nervous disposition”. Meek had also begun recording with Screaming Lord Sutch. Sutch had already made a name for himself with outlandish, joke-shop horror shows where he’d splatter the audience with fake blood. On tracks like ‘Till The Following Night’ and ‘Monster In Black Tights’ (with its camp ‘Carry On’ lyric co-authored with Goddard), Meek surrounded Sutch with intensely detailed audio montages of creaking coffins and doors, with howls and screams echoing into infinity.

This is the Meek sound at its zenith, when his confidence was so high he wouldn’t have cared if the whole street were banging on his door. Unaware and lost in his muse, he would tell them to piss off or ignore them. In later years, he would try to accommodate them, wearied by their complaints. A reel of surviving demo tape has him asking Goddard not to tap his feet while playing piano “in case the people next door start banging on the walls”. When there was time to spare, Meek would spend hours on his own, wailing tunelessly over inappropriate backing tracks in search of one more hit.

“Most of the guys would laugh at him doing that,” said Hodges, “but some of us believed in him and wanted to help. You knew that in there, among all the dang-dang-doing-doing-doinging, was a tune. He had a way with music, but it was a strange way.”

“We were recording a tryout for a new ‘Ready Steady Go!’ theme he’d been asked to do”, said Tony Dangerfield, who died in July 2007. He was a young singer and bass player in Sutch’s Savages and recorded two solo singles with Meek. “He kept singing this weird tune to us and we tried desperately to translate it for him. It just wasn’t working and I remember him running out of the studio crying.”

The industry was now unable to ignore Meek and, bit by bit, invited him to join the party. His hard work seemed to be paying off, but not without a price. “People say I’ve been working too hard lately, that I’m ready to crack up,” he admitted in one interview.

“He literally drove himself into the ground,” said Goddard. “He was suffering from mental illness anyway, I’m sure. He once told me without joking, that he thought something was growing inside his head.”

Meek always had space on his mind, and with the launch of an American communications satellite called Telstar, he returned once more to the shorting wires and radio interference that had transfixed him during the recording of ‘I Hear A New World’. Powered by the futuristic sounds of the pre-electronic Clavioline keyboard, ‘Telstar’ orbited into view.

A member of Meek’s Syndicats at the time, Steve Howe (later of Yes fame) had no interest in being interviewed about anything when I contacted his management company in July 1999… until, that is, I mentioned I wanted to speak Meek. He said that when he hears his records, he can clearly envisage Meek at the controls.

“His studio seemed to come alive when he worked,” he said. “Sparks would fly in there. He was a performer and an artist. So much more, really, than a record producer.”

On what became Meek’s unquestioned signature tune, the Space Age was defined for all suburbia to hear. Despite complaints from the Decca technical department, who were “horrified at its levels of limiting and compression”, the record was released in August 1962. It made Number One and stayed in the charts for the next six months.

‘Telstar’ compacted the hours Meek spent putting together ‘I Hear A New World’ into a handy two-minute futuristic chunk. Nobody could claim that he invented science fiction. Hollywood had B-movied itself to death with aliens in silver diving helmets since the 1950s, but sonically, ‘Telstar’ mirrored the genius of Louis and Bebe Barron’s ‘Forbidden Planet’ and the likes of the early Sun Ra in his ‘Rocket Number Nine’ taking off for planet Venus. As a pop record, ‘Telstar’ is a defining moment. The Tornados followed up with diminishing returns like ‘Robot’ and ‘Life On Venus’, but their place in history was bookmarked already.

Pleased as punch and with money in the bank, Meek bought himself a Zodiac and celebrated by making a vocal version, ‘Magic Star’, with one of his boys – a teenage Kenny Hollywood, whose voice was almost as bad as his own. Meek hardly noticed when, complete with mind-numbingly romantic lyrics, it sold next to nothing.

The clomping teen spirit of ‘Just Like Eddie’ was his next significant success. This paean to rocker Eddie Cochran was hardly subtle, but Meek simply required a hit. With Ritchie Blackmore, by now a Meek session regular, providing scorched earth guitar, the track indelibly stains the memory with a single hearing.

“It’s a beautifully made record. You can hear that so much effort was put into it,” said Ted Fletcher, who worked with Meek as an assistant from 1963 to 1966 and these days runs studio equipment company TFPRO, launching a successful Joemeek brand in 1993. “The equipment used back then was so primitive in today’s terms. When you listen to ‘Just Like Eddie’, you know it’s almost impossible that he could have squeezed any more energy out of the set-up he had.”

As the pills kept him fizzing with fresh ideas, Meek recorded a run of flops (by the standards of the time). Even though they didn’t make the charts, they were sold to the major labels for big money, the kind of money a man of substance, now with real hits to his name, could command. These records have subsequently become latter-day Holy Grails for Meek geeks. They underline his idiosyncratic vision with startling success. With releases by Gunilla Thorn, The Thunderbolts and Geoff Goddard (the unbelievably rustic UFO anthem, ‘Skymen’, a tribute, said Goddard to “our friends in space and the sighting of extra-terrestrial beings over Reading”), Meek was still on a high in more senses than one. It’s the pop hits that cornerstone his story, but it’s these records that laid the foundations of an unlikely legend.

Although Meek never seemed to come out from behind his compressors and tape machines for longer than it took to bollock someone for a bum note, there was a life outside of music to be led. The Tornados’ B-side, ‘Do You Come Here Often’, in which two unknowns parlay camp gags over a deliberately cheesy organ intro, showed he was getting about and was unafraid to admit his “scene” connections – “Well I must be off / You’re not looking so good / See you down The ‘Dilly / Not if I see you first”.

On 11 November 1963, Meek was arrested for importuning in a gents’ lav at Madras Place, Holloway. It transpires that he may well have been set up but, as a regular visitor to this notorious cottaging hang-out, he was bound to have his famous collar felt sooner or later. The police claimed he had “smiled at an old man”. He later objected to the injustice saying, “Who wants a fucking old man?”. He was fined £15, which would hardly break his bank, but the scandal made the national press at a time when homosexual men were treated as if they had an incurable disease.

By this stage, Meek talked about the men he picked up in Madras Place like a junkie does his fix. He had spoken of such liaisons “easing the pressure” he had put on himself. But with a ready supply of fresh blood at his studio, young men eager to get on who were willing to do anything for a recording tryout, it was hardly like he needed to put himself in such danger. Certainly, he was not shy of asking youthful musicians if they wanted to “come upstairs”.

“Sex was always on the menu if you were like-minded and you wanted to get on,” Mike Berry said in June 1999. He recalled his band, The Outlaws, would take the piss out of Meek behind his back, calling him “Tweedledum” and mimicking the way he combed back his hair constantly. The 18-year-old Steve Howe also had to deal with Meek’s quietly predatory ways.

“He used to tell me he liked my trousers,” Howe told me. “Then he would call me into the office. I would always go because I was keen to get some more session work. I was terrified when he’d come on to me. It was like meeting some shady guy in a mac in some Nags Head somewhere.”

Chas Hodges, at the time just 16, recalled a Saturday afternoon watching the wrestling in the flat above the studio. Meek asked him in his quiet country burr if he liked the wrestling, then made a grab for his balls. Interviewed for an ‘Arena’ documentary, ‘The Strange Story Of Joe Meek’, Screaming Lord Sutch grins as he says, “He was always asking members of my band to stay over, ‘to do a bit of overdubbing’. They’d say, ‘I’m not going up there on my own’. But it was never the ugly sax player or the drummer without any teeth”. Peter Meer, a member of The Hot Rods who recorded at Holloway Road, would sometimes sit and watch TV with Meek.

“One time he put his arm around me. I said to him, ‘What’s going on?’. He said, ‘People put their arms around each other in pubs’. I said, ‘This isn’t a pub’. He looked a bit embarrassed and said, ‘I’m just trying to be friendly, I’m just trying to see what you’re like. I’ll still listen to your songs’. There was something really sad about that when I think back. A real loneliness.”

The thrill and potential danger of cruising outside of his studio environment seemed to fascinate him, though. He had feared the effect such a thing might have on his career, which was what really mattered to him, but by now it was too late. Two days after the Madras Place story got out, he pinned one of the press stories to the studio wall. “Fuck ’em”, he was heard to say before the session in hand continued. But his apparent nonchalance was to be short-lived. People began knocking at his door with blackmail threats, claiming he had slept with them, their friends or members of their family, and demanding money before they passed their stories on to the press. Meek paid up fivers and tenners, but that just multiplied his problem. Word got around that he was an easy touch.

“Everything went wrong after that importuning offence,” said Goddard. “I heard that people had broken into the flat and threatened him. It got scary. In the early days, if a session ended late at night I would walk down to the tube station. Later on, I would get a cab to come to the door and take me home.”

Meek’s moodiness and mercurial temper were much more prevalent after Madras Place. With The Beatles on his tail, developing a sound that elevated the group above the producer/auteur Meek so obviously was, his “matchbox music” jibes showed he was feeling the heat. Still, there was always the hope of another fix of happiness. The Number One success of The Honeycombs’ gonzoid, stair-stomping classic ‘Have I The Right?’ provided the jolt he needed. Ego and attitude held sway once more. He went in all guns blazing when Dave Clark’s ‘Bits And Pieces’ made its way onto the horizon. With typical petulance, Meek claimed they had stolen his “stomp” sound.

Otherwise, the walls were closing in, in so many ways. Goddard was suing, not Meek, but the writers of ‘Have I The Right?’, claiming he had penned the song. Curiously, Meek sided against his seance buddy and the pair fell out. With Tom Jones having hit the big time with ‘It’s Not Unusual’, Meek decided it was a good time to dust off a recording session he’d done with the sandpaper-throated Welshman a year earlier. Jones was pissed off and did little to hide the fact in the pop press. Meek was again under attack.

Meek popped more pills, both uppers and downers. He consulted mediums and Tarot cards and continued with his beloved seances, calling up Buddy Holly and spiritual pals like the Egyptian pharaoh Rameses The Great, to ask advice on his increasingly troubled life. In an interview with the fan club magazine Thunderbolt, songwriter Tony Grinham said Meek had confided he was experimenting with LSD. “He said he had had some bad experiences. In one, he saw himself on a raft, lost at sea.”

With The Tornados having bitten the dust, Meek tried to revive the name with new musicians. Mitch Mitchell, later to play with Jimi Hendrix, was drafted in on drums. Mitchell played like his life depended on it, but it was too wild for the controlling Meek. Mitchell didn’t get the message as Meek stomped about demanding the individualistic drummer do exactly as he asked. He continued as he had done before and Meek is said to have emerged from the control room with a shotgun promising, “If you don’t do it properly, I’ll blow your fucking head off”.

Meek met the challenge of changing times better with beat boom classics like David John And The Mood’s blinding ‘Bring It To Jerome’, and the stunning Syndicats’ B-side ‘Crawdaddy Simone’. With all effects guns on stun, Meek aided and abetted The Syndicats’ guitarist Ray Fenwick in an intergalactic blues solo the equal, in intensity at least, of any Hendrix nugget. It was a freakbeat masterpiece.

“He got so excited,” remembered Fenwick, when I spoke to him in late 1999. “He was so pleased that he seemed to be getting his head around this beat boom sound.”

On ‘Bring It To Jerome’, Meek recorded a toilet chain being dropped in a rusty biscuit tin to give the percussion a typically distinctive edge. His studio was chock full of rubbish. It was apparently hard to discern whether the lengths of lead piping were to be used to beat the drums or to threaten someone with. Either way you had to be careful in there. With wires held together by chewing gum and a trusty spring echo, a garden gate spring stretched out and nailed to a plank, 304 Holloway Road was as dangerous a place to be as it sounded.

When I spoke to session drummer Bobby Graham, who died in September 2009, he said Meek was constantly shouting “Don’t tread on the wires, you’ll ruin me sound”. Graham says there were many times when the artists had to hold back from losing their temper with him.

“I’d drag a bloody drum kit up three flights of stairs, set it up and he’d say, ‘No, I don’t want you to play the drums, I want you to try something different, I want you to play the drum cases today’.”

The madness of Joy Division producer Martin Hannett seems hardly worth mentioning by comparison.

Brian Epstein made contact when Meek had a hit with ‘Please Stay’ by Liverpool group The Cryin’ Shames. They left to be looked after by Epstein, despite his jealous pleading. This was a painful nail in the coffin of a man now seeming to trace ever-decreasing circles. All and sundry were accused of helping others plant telephone bugs and listening devices in the flat. In his increasing madness, and with the major labels turning down more and more of his productions, he was resolutely convinced that his recent lack of success was down to others stealing his ideas. There are stories of the many people who came and went at 304 walking off with information and acetates that may easily have found their way into the hands of interested others. Meek placed bugs about the flat himself to see if he could catch anyone talking about him. He was off the rails in so many ways.

Phil Spector, who was visiting London and was apparently a fan, called to tell Meek how much he loved his music. The call was taken by Clem Cattini of The Tornados, who then heard Meek shouting at Spector that he’d “stolen his secrets”.

“He slammed the phone down so hard that the receiver cracked,” said Cattini.

The following Christmas without a trace of irony, Meek was said to have bought a box full of Spector’s celebrated Christmas LP, giving them out as gifts. Steve Howe remembers these as strange times at Holloway Road.

“There was an impending sense of doom about the place,” he said. “And there were always arguments going on, with sundry Tornados running up and down stairs, banging doors.”

His nocturnal lifestyle picked up pace again. He was once spotted flying down the Holloway Road in his pyjamas, screaming that someone was chasing him with a knife. Another time he was found beaten up and unconscious, hanging out of the side of his well-known, red Ford Zodiac. Whether this was something to do with his sexual tourism or something more sinister, relating to talk of London gangland attempts to muscle in on his conspicuous wealth, is still open to question.

On 16 January 1967, the body of 17-year-old Bernard Oliver was found at a Suffolk farm. Meek knew the boy and was alarmed when newspaper reports mentioned police were planning to question all of Oliver’s known “associates”. He had been chopped to pieces and dumped in a suitcase.

With the ‘Telstar’ case still unresolved, by now Meek was broke. He was hiding from his creditors and the hits had all but dried up. In his 2001 book, ‘The Legendary Joe Meek: The Telstar Man’, John Repsch talks of him only eating when assistant Patrick Pink brought food he’d stolen from his own family’s cupboard. His new recordings were still being turned down. Seance calls to Rameses The Great and, it’s said, Aleister Crowley for advice, did nothing to help.

His mind awash with pills, and with the police, he was sure, closing in on him, his state visibly took a turn for the worse. He looked worn out and had taken to dressing completely in black. Whether Meek was actually in any way party to the murder of the boy, or he simply felt he could not stomach the blows dealt by another newspaper scandal initiated simply by his being questioned, is not clear.

On 2 February 1967, he set up for a recording session with Patrick Pink, as he had promised. He asked his assistant to mime to the music because he knew the place was bugged. Pink left him to get on with it and when he got up in the morning, Meek was still in the studio. Pink noticed he was urgently sorting things out, tying things up, perhaps. He was writing notes and burning them in case the “spies” found them. It was clear Meek was expecting the police to call any day.

He returned to his studio where he handed Pink a note that said “I’m going now. Goodbye”. Meek continued tinkering with the track he was putting together when one of his helpers, a boy called Michael, started banging on the door. Meek dispatched Pink downstairs to send him packing. While he was there, he shouted for him to send his landlady, Mrs Shenton, up. Meek could be heard shouting about “the book”. He could only have meant his rent book. It seems likely that Mrs Shenton had retained it and was intending to throw him out, finally having had enough of the hit-searching stomping and the fact that Meek hadn’t kept up with his payments.

An argument ensued. Mrs Shenton is said to have turned her back to return downstairs and Meek blasted her, as she walked away from him, with the shotgun Tornados’ bassist Heinz Burt had left among his belongings when he’d exited the flat some time before. Pink tried to tend to her. He called out to Meek, “She’s dead”. That seemed to be the cue for Meek to reload the gun and point it at himself, blowing his own head off on the same date his hero Buddy Holly had died in 1959.

Whether this is coincidence or a deliberate decision on his part, depends how far you get lost in this fantastic story. Both Burt, who owned the gun, and Pink, the only witness, were treated as suspects and subjected to a serious police grilling. Meek made the papers one more time as the tragic events became clear. “Top Pop Man Shot Dead At His London Studio” screamed the headline.

“His suicide was no surprise to me,” said Goddard. “It was a logical end to the pressure he put himself under.”

Among the last dozen recordings that made it to release was The Cryin’ Shames’ poignant ‘Nobody Waved Goodbye’. At Meek’s funeral in his hometown of Newent, 200 people turned up.

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

Joe Meek was largely forgotten until his records began to fester in the minds of a few obsessives in the mid-70s. It is only in fairly recent times that the contemporary appreciation of Meek’s sonic vision and his uniquely British garden wall of sound, together with the appeal of an irresistibly absurd and tragicomic story, that he has become an icon.

“There was no doubt that he was genuinely hated by the record industry establishment,” said Ted Fletcher. “He made them look stupid.”

But the Meek, they say, shall inherit the earth. Maybe Joe himself might come back, summoned from the mists by an upturned glass in a darkened room full of Meek geeks, to collect the praise he so richly deserved. Not that real adulation and respect in his day would have changed anything. Like a rocket pointed at the stars, he seemed to be on course for self-destruct long before he realised it himself.

Beyond the enduringly fascinating story of his life, Joe Meek left a significant musical legacy that still resonates. His instantly recognisable manipulations, lurking just below the surface of many of his records, speak of a necessarily crazy creative genius. His unhinged and uncompromising approaches later became commonplace tropes in the work of mavericks like Lee “Scratch” Perry or Cabaret Voltaire – people relatively understood and working long after an era that often intentionally attempted to stifle Meek and his one-man, back-bedroom, Heath Robinson rebellion.

‘I Hear A New World – The Pioneers Of Electronic Music’, a three-CD set that places Meek’s masterpiece in a broader context, alongside seminal works by pioneers including Daphne Oram and Edgard Varèse, is avaialble on Cherry Red