Originally published in French in 2003, Laurent Garnier’s book ‘Electrochoc’ finally gets an English version. We talk to the author and, in an exclusive extract, he casts back to 1993 and recalls his very first visit to Detroit

“You would need to ask the English publishers,” guffaws Laurent Garnier after a long, thoughtful pause following our opening question. Why has ‘Electrochoc’, a book that combines the history of dance music with Laurent’s own journey to the top table, taken 12 years to come out in English?

“When the book first came out, we tried so hard to find an English publisher,” sighs Laurent. “They would say, ‘I don’t think it’ll interest anybody in England’. Some of them actually said, ‘We would do it if you were Carl Cox or Pete Tong… but you’re not!’. After a few years, I got a bit annoyed by the situation. I really wanted this book to exist in England, because there were so many people asking me about it.”

Taking matters into his own hands, his British wife Delia (a translator by day) set to work on the manuscript and a meeting with a small independent London publisher, Rocket 88, landed the English version a deal, with Laurent and co-writer David Brun-Lambert penning a new chapter covering the decade or so since the first edition.

‘Electrochoc’ is a beautifully crafted tale that weaves the story of Laurent’s own remarkable career in and out of the history of dance music, which it turns out was unfurling in front of his very eyes. From early 80s London and the Mud Club, to Manchester and The Hacienda, to Paris and the Rex, to Detroit, New York, Chicago and beyond…

“We thought it was nice to use me as the person who was travelling his little life, and in and around it we’re just explaining what was happening in a more global way,” says Laurent.

Laurent was very much a man in the right place at the right time. If he hadn’t taken a job at the French Embassy in London, he might not have found the Mud Club. If hadn’t wandered down Whitworth Street in Manchester, he might never have seen The Hacienda.

“Exactly, but everyone is like that,” he says. “If you had woken up at 6.40 instead of 6.45, maybe you wouldn’t have taken your car and had an accident. It’s just where life is taking you. But it’s true that I was at some places at the right time and I got to meet some interesting people. Without the things I decided to do, I would never be who I am now. I can’t really regret anything. I’ve been very lucky.”

It’s been said that Laurent’s early Hacienda sets as DJ Pedro were a major inspiration on The Stone Roses and Happy Mondays. Quite a string to the old bow, no?

“It wasn’t just DJ Pedro,” he laughs. “Everybody was feeding off each other back then. Without the influence of The Stone Roses or Happy Mondays or New Order, maybe the club would not have been the way it was. We were all part of the same thing at the beginning. We didn’t know where the hell we were going.”

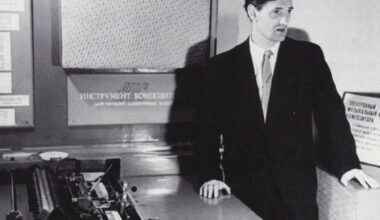

We’d be here all day and half the night picking out the highlights of ‘Electrochoc’, but it includes some fascinating interviews, most notably with Jeff Mills and Mike Banks, who talk about the development of Detroit techno. The discussion is weaved in and out of the story of Laurent’s first visit to the city in 1993.

“Detroit was always very important to me before I went there,” he says. “As I say in the book, it’s not because I went there that I love the music from Detroit more, it’s just that I understood what those guys meant and what they wanted to do.”

There’s a scene where Laurent and Kenny Larkin arrive at a restaurant for dinner one evening, to find Derrick May, Mike Banks, Kelly Hand and Berlin producer Maurizio sat around the same table.

“You’re sitting down with these legends and people are just walking past, not giving a shit,” he explains, incredulously. “If they had been American footballers or baseball players, everybody would have stopped. Seeing that, you start to understand why it never happened in Detroit for them and why they had to come to Europe to make a living.”

So what next? What does he think he’ll be writing about if he updates the book again 10 years down the line?

“Why did we all jump on this particular music?” he says. “Electronic music was the last true revolution. Nothing else has happened like it in the last 30 years. It must be weird for these 18-year-olds who listen to house music today, because basically it’s music that belongs to their parents. I really hope something musically will happen one day which is as big as this, something that’s going to truly change the course of everything.”

Laurent Garnier first visited Detroit in 1993. In our exclusive extract he ponders the importance of the city as a musical guiding light…

My plane landed in Detroit at around 5pm local time. I was questioned several times over at border control without really knowing why. Eventually, the US immigration officer got bored and stamped my passport. I passed through customs and stepped outside through the security doors. I jumped into a cab and gave the driver Kenny Larkin’s address. He was waiting for me at his house in the white suburbs of Detroit. The taxi pulled away and sailed onto the ring road. Once we had crossed the invisible boundary into ‘downtown Detroit’ I began making out the city’s wide avenues. It was getting dark. The headlights faintly lit the decrepit walls lining the streets. Buildings resembled crumbling mausoleums. In the distance I saw two towers bearing the letters G and M. The taxi driver pointed them out to me as if proudly showing me the ruins of a local monument, ‘You see right there, that’s General Motors!’ On top of the steel and glass towers, the red and blue letters overlooked the down-at-heel city.

In the taxi, I was trying to recall when I had first heard the name Detroit. Was it in the 90s, via techno? Or through Motown soul? Soul and techno: two by-products of the same story of suffering and sincerity. One thing is for sure, I have always associated Detroit with music. For the likes of me, having grown up with music, Detroit is the mark of quality, whether experimental jazz or rhythm ‘n’ blues, the invention of futuristic funk by George Clinton or the cries of anger of MC5 and The Stooges, and, of course, the unforgettable sound of Motown.

The US itself seems to have a hard time remembering Detroit as a musical guiding light, whereas in Europe Detroit is regarded as a city overflowing with innovation, groove and perfection. And for people like me, Detroit is the birthplace of techno, a place of hardship, where jazz, the last great music of the century, underwent a change and evolved into electronic music. Techno can be considered the urban continuation of jazz. Be it John Coltrane or Derrick May, their obsessions are the same: space, time, groove and unfathomable melancholia. I was in Detroit for a special reason, to soak up the vibes of the city and to meet my techno heroes. I hoped to reach the purity and great sadness that permeates the music and understand why Detroit’s music exudes such emotion, so much hardship, so much experience and so much beauty. I had expected to arrive in a rundown city and have a hard time getting to grips with the mystery that is Detroit. I had planned on questioning everyone I met there and interpreting every sign. But instead, all the answers could be found just by looking at the history of the city.

Like Manchester in the early 1800s, during the golden age of the British Industrial Revolution, Detroit also became the great American city of industry. Several thousand blue-collar workers came from all over the US to work at the Ford automobile plant, while the black workers were confined to the foundries. Greek immigrants founded Greek Town and the first black community within the city settled in a ghetto known as Black Bottom. It was there, on Hastings Street, that the first temple of the Nation of Islam was built.

In 1932, after the Wall Street Crash, Detroit was nicknamed the ‘green city’, as there were more trees per square kilometre than in any other city in America. World War II marked the second golden era for Detroit, a.k.a. Motor Town, as it became ‘democracy’s arsenal’. B52s were built in the Ford factories and army tanks at Chrysler. Then jazz appeared and the Black Bottom ghetto was knocked down and replaced by a motorway. In 1959 Motor Town gave birth to Motown, the cultural pride of the black community. Then the battle for civil rights broke out in the US, and in July 1967 Detroit experienced three days of bloody rioting. Then began the city’s slow downfall. It began with the closure of automobile factories. The white community fled to the suburbs and the ghetto grew bigger and bigger. And finally, in the 1980s, there was an explosion in drug abuse, especially of crack, in these same ghettos.

Detroit techno music tells the story of all of this hardship. And within this music one can feel the life force that refuses to be put down. Words are of no importance. Everything is expressed within a few notes, repeated ad infinitum. Detroit techno is made of metal, glass and steel. When you close your eyes you can hear, far off in the distance, then closer and closer, the echo of crying. Like in jazz and blues, Detroit techno transfigures suffering. This authenticity of spirit has no price.

At the beginning of the 1980s, Detroit was still a sounding board for American record companies. If an artist made it in Detroit, the labels felt that artist could make it across the US; the majors trusted the local Detroit radio stations and their DJs. The influence of Detroit radio DJs would play a critical role in the future of young artists and the emergence of new musical trends. Today, every single DJ and producer who made up this first wave of Detroit techno artists still talks about Electrifying Mojo’s radio show. He was a visionary, who mixed European electronic music with early black music. Mojo was the first to play prime-time Prince and A Certain Ratio, Funkadelic and Kraftwerk, Visage, New Order, Pet Shop Boys, the B52s, Falco and even the French violinist Jean Luc Ponty. Everyone agrees that Mojo was the person who created the framework on which to hang Detroit techno.

In the middle of the 1980s, another DJ appeared on the Detroit radio scene, known as The Wizard. The current hip-hop generation in Detroit grew up listening to him. And to this day, on the rare occasions that Jeff Mills performs in Detroit, you will still find hip-hop fans at his gigs who would never normally venture into techno clubs. It’s not rare to overhear in a conversation, ‘Eminem and his posse came down to listen to The Wizard’.

His technique, innovation, knowledge of mixing and the mystery that shrouded his true identity resulted in him becoming a legend within the city. Almost 20 years later, Jeff Mills still remains The Wizard.

‘Electrochoc’ by Laurent Garnier with David Brun-Lambert is published by Rocket 88