Sonic pioneer and one half of Mouse On Mars, Jan St Werner contemplates the materiality of music, self-conviction and life as a creative listener

Organic Upbringing

“My parents split up quite early and it was not the happiest of situations, so I ended up living in the countryside with my grandparents. My grandfather played the church organ in my village and, sitting next to him at the organ, I was able to change the registers. He would tell me what would be needed next, and I could add some low-end and add some reed. It was basically filtering and changing resonances and overtones. That’s still probably an ideal to me, to be able to listen to what’s going on and then change the sound on the way. You can play it yourself and initiate the event, if you need to, but if it’s someone else playing that’s equally exciting. The sound of that instrument was quite an influence.”

Beauty And The Beasts

“My intention isn’t necessarily to dissect things or question them profoundly. It’s more an impulse, a matter of speed. I see something and then almost immediately think, ‘I see it differently’. It’s a switch, and these switches come very quickly and they don’t destroy the pleasure you have engaging with something. Close friends sometimes say, ‘Why don’t you hold onto that moment and repeat the melody? Why do you make it so difficult for people?’. I don’t see it like that, it’s just a switch of perspective. You hold on to the pieces of beauty you’re given. That’s something I figured out quite early – that there’s a certain destruction in everything that seems complete.”

Fake It ’Til You Make It

“My parents were artists, but had to make their living doing applied work. My grandfather taught choir and played the organ, but wanted to be a composer. My grandmother considered herself a noble person, but she was totally working class, poor to the bone after the war. Seeing all these people pretending to be someone else, maybe that made me be a popstar, in a way. It made me realise a person could be anything, and there would be no reference as to whether you’d really succeeded in being what you aspired to be. As long as you believe you are, the rest of the world, to a certain extent, will align to that.”

We Built This City

“There was a cassette player that somebody brought to our house, and I immediately figured out you could record tapes by closing the locking mechanism. I could make pretty amazing collages. I made my first recordings when I was six or seven. I used them as ambience, basically. I would dub sounds from the TV, then I would stop recording and have some original stuff, and then hit record again. I used them to play, as soundtracks for these ‘future cities’ that I would build out of styrofoam. The biggest styrofoam was the best. I would walk to the local electronics stores and ask if I could have packaging material.”

Punching-Up

“I was lucky that I found myself in situations where I could grow, where I was a bit over-challenged. I started drumming as a teenager, and met these older musicians, so I was asked to play on a record when I was 16. I was invited by a local jazz drummer and bassist, and at the time I had just started listening to David Sylvian, his post-Japan stuff with Holger Czukay. There weren’t that many people in the town into that stuff. These guys were like, ‘You should come and play with us’. I never heard the record I played on! Then, when I went to Cologne in my early 20s, I met all these people from A-Musik, the experimental label, and then I met Andi Toma, and it all accelerated so fast. Mouse On Mars just made music for fun, but it became a proper band.”

Handy Andi

“Andi was confident enough to say, ‘Let’s spend our time making it as good as possible’. I love arranging and editing, and minutely placing shit, but in the end, I don’t care that much how it sounds. It sounds different to everyone, anyway, but Andi always had a really specific idea about what he wanted, and it’s really hard to please him. Even today, he’s still like, ‘I’m not happy with the mix, let me do it again’. I think we gave each other courage in unpredictable ways. It’s still really great to work together. He’s such a musical person, he can do anything. It’s a good basis for a partnership.”

Sound Idea

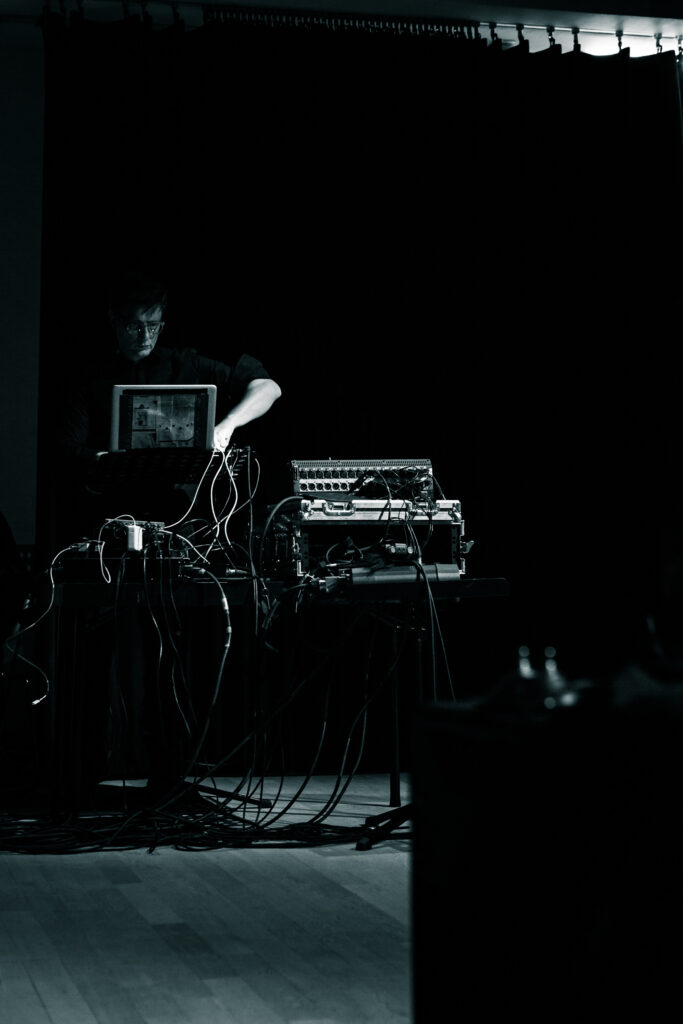

“I still wouldn’t consider myself a musician. I use music instead. I see sound as a material. Music is so fragile and absurd, we take it for granted and think it’s solid, but it’s a dubious model, whereas sound for me is very real. Even people who have hearing problems react to vibrations and, extending that, waveforms, so can you touch music? What the brain does with sound still hasn’t been fully explored. We know it actively reacts and actually adds to what you hear, based on your preferences and experiences. It’s playing your ears, like a puppet on a string. The brain is good at giving us a picture, but that is fragile and changes all the time. I know I won’t be done until I die, but I want to peek through as many holes as possible in that insane sponge that we call sound.”

Jan St Werner’s ‘Glottal Wolpertinger’ album is out on Thrill Jockey