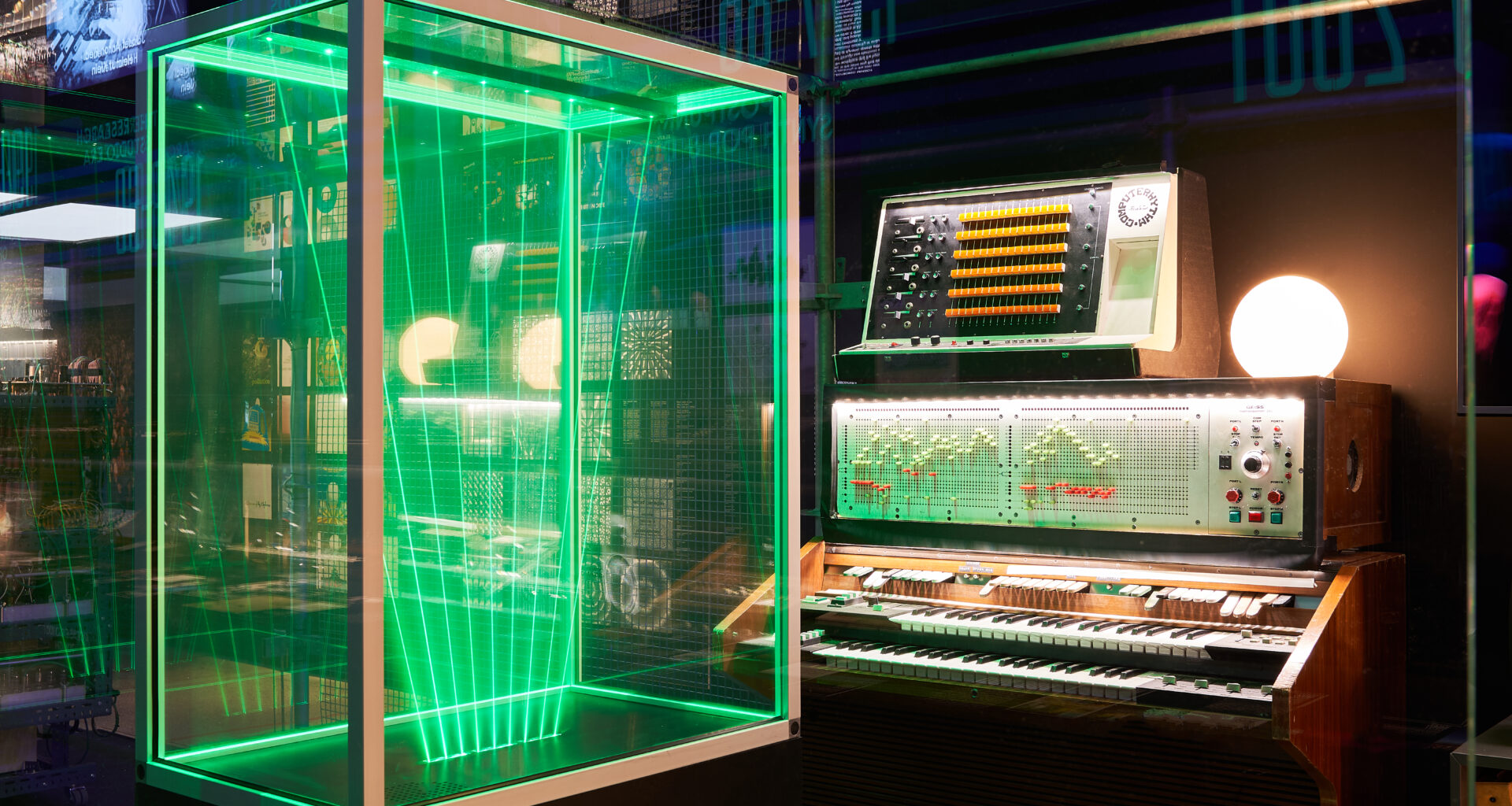

Four months later than originally planned, the Design Museum in London hosted ‘Electronic: From Kraftwerk To The Chemical Brothers’, a remarkable retrospective of electronic music

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here