Our esteemed columnist Has been unusually quiet of late. And then, like magic, up he pops up with news of his exploits… it’s quite a tale as you’d expect

In recent weeks, a top secret project has seen me re-living the seven magnificent years I spent with The Clash between 1976 and 1981. They rose like a meteorite from the punk movement then transcended it to pinball through relentless cathartic mayhem and self-created disaster to create a legend like no other band in history.

Over those years, initially in my role as Zigzag editor, I went on the tours, witnessed classic tracks being recorded and explored the new musical strains they discovered, assimilated then remade in their own unique vision.

Facing this month’s column with The Clash still electrocuting my soul, it makes perfect sense to highlight their much-overlooked relevance to the Electronic Sound universe. It might have started with the dub reggae excursions that accompanied singles like 1979’s ‘Armagideon Time’, 1980’s ‘Bankrobber’ or littered the controversially-experimental ‘Sandinista!’ triple album but, by 1980, The Clash were also blazing newer electronic trails, incubating tropes soon to be hijacked by synthpop, exploring the potential of 12-inch singles, crossing over to the then-underground hip hop ethos and paving the way for electronic dance music in the mid 80s.

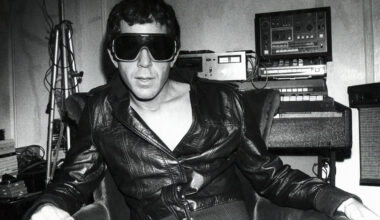

As his post-Clash outfit Big Audio Dynamite affirmed, much of this pioneering came from their singer-guitarist Mick Jones, paradoxically one of the last century’s most sensitively passionate rock ’n’ rollers who found himself relishing the eye of a new hurricane when The Clash started visiting New York in 1979.

Mick was the Clash member I got particularly close to and every time I went to his flat he had some hot new 12-inch biscuit to play at brain-shattering volume. One evening in December 1982, he said “Happy Christmas” and pressed a cassette into my hand that he’d recorded off the radio in New York; a treasure trove of the KISS FM and WBLS mastermixes which were then hot currency in London. These electronic mini-masterpieces cleared the mental landing-path for the approaching remix culture by extending grooves and adding samples, whether Run DMC (among the first drum machine-users in hip hop), New Order or, of course, The Clash.

‘The Magnificent Seven’ had started life when Blockheads Mickey Gallagher and bassist Norman Watt-Roy arrived at New York’s Electric Lady studios in April 1980 and laid down a groove Mick said needed to be funky because Joe was planning a rap. ‘The Magnificent Seven’ would turn out to be one of The Clash’s epoch-making tracks, marking their first stab at assimilating the new hip hop busting out in New York.

“I was so gone with the hip hop thing that the others used to call me Wack Attack!” Mick told me in an interview for my 2004 book ‘Joe Strummer And The Legend Of The Clash. “I’d walk around with a beatbox and my hat on backwards. They used to take the mickey out of me. I was always like that about whatever came along; I’d sort of get excited for a while.”

Mick’s dub of ‘The Magnificent Seven’ was a grooving workout called ‘The Magnificent Dance’ that swept NYC radio (I witnessed Larry Levan slaughter the Paradise Garage with it in 1983).

Although The Clash would later be acknowledged as the first white rock band to explore rap, none of the New York DJs playing the record had any idea who was responsible at the time. Talking about it over 20 years later, Mick was typically modest about his band’s place in pushing the sonic goal-posts at this pivotal time.

“It was quite inspiring, because there was this whole new thing. They did things like putting bits of movies on top. There was this mix on WBLS called ‘The Dirty Harry Mix’ that used that bit that goes, ‘Do you feel lucky today, punk?’ It also had characters from Bugs Bunny; ‘De wabbit kicked the bucket’. That was kind of a pointer, yeah.

“For us it was amazing because they’d picked up on this record, particularly the instrumental, and didn’t know who we were. Everyone was playing that record and it turned out to be us! It was really funny because we were punk rockers! And we’d come all this way. You couldn’t have written or contrived it. I guess we did the first proper 12-inch dance mixes too, but it wasn’t planned that way. It just happened. It was just lucky really.”

There was also 1980’s ‘The Call Up’, taken from ‘Sandinista!’, its 12-inch boasted Mick’s out there dub ‘The Cool Out’, and the following year’s ‘This Is Radio Clash’ with the astonishing alchemical mash-up of ‘Outside Broadcast’ stretching the track into a ghostly groove-voyage garnished with Gary Barnacle’s eerie sax, mutated funk riffs and Joe’s slowed-down rap.

Later that decade, all this would be considered a normal promotional tool but, at that time, expanded mixes on 12-inch singles were usually only encountered on disco, hip hop and reggae outings. By the end of the 80s, remix culture would be rife with big names earning more than the artist to reassemble a single for the dancefloor.

Despite all this, Mick never consciously thought The Clash were making music that would later be hailed as groundbreaking.

“We never thought that, at any time,” he says. “We were just knocking out some numbers. We just wanted to do our thing. We didn’t necessarily want to be part of this big, happening thing that was so cool. We just did what we wanted to do.

“I guess it’s because we had that kind of attitude. We were so open to other things, and we attracted it as well. We were open to meet other artists in other fields. The Clash’s involvement in the start of that whole thing was by luck really. We were in the right place at the right time. If you travel with a group like that you’re bound to find out about all the things that are happening much quicker. It’s like a fast track to what’s culturally happening in whatever place you go to. We were fortuitous in the fact that we attracted all the different, creative people to what we did. They came and checked us out.

“What had started as a punk group turned multi-national. We took on different concepts and tried to make it part of hat we were doing, but still retaining our own thing. We did it our own way, not by slavishly following fashions. It helped some people find a way in to these things. You wouldn’t have known that when hip hop was in its genesis that it’d become one of the major forces of music later on.”

Did The Clash invent acid house and remix culture? They undoubtedly played their part. No other band came close to capturing that excitement during that short but seminal time. And let’s not forget, if it wasn’t for The Clash inviting them, Suicide would never have invaded the UK as early as July 1978. See you next month.