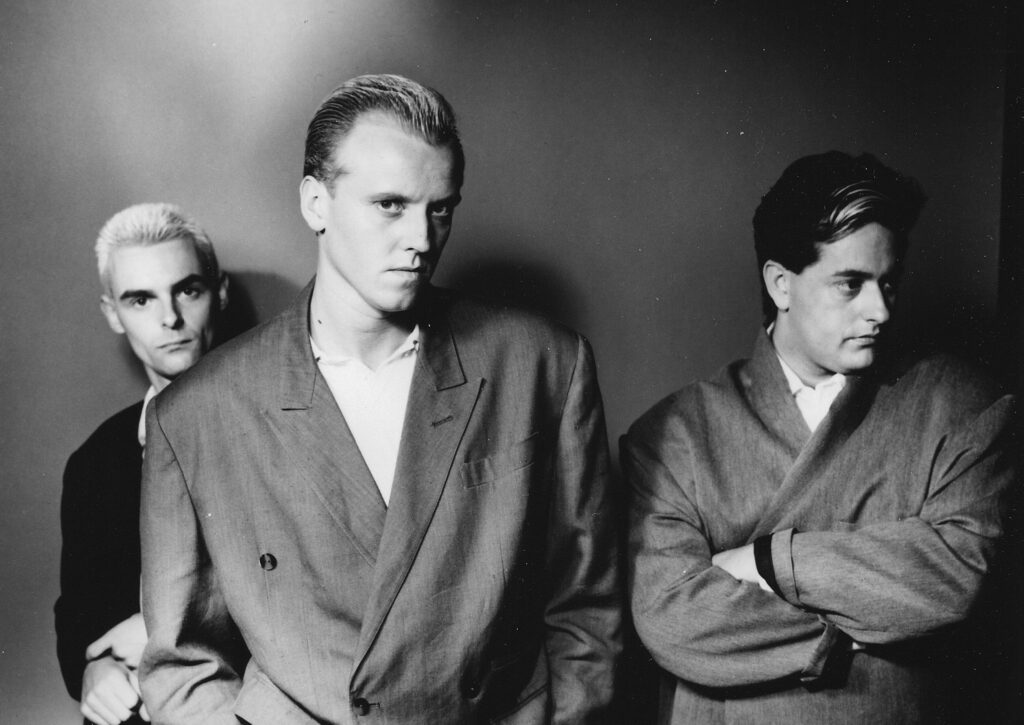

You might know ‘(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang’ as a Heaven 17 song, but it started life as ‘Groove Thang’, an instrumental on BEF’s cassette-only debut, ‘Music For Stowaways’. Martyn Ware explains how the track liberated him from The Human League’s synth-only policy and helped him uncover a very rare talent

The story starts with the Sony Stowaway, which was what the Sony Walkman was originally called. They changed the name after about six months. I don’t think the name Walkman was as good actually, I still like Stowaway better. See, a Stowaway would be a great name for a tiny little MP3 player, wouldn’t it? When the Walkmans came out, I distinctly remember thinking that it meant you could design a soundtrack for your everyday life for the first time and have it playing while you walked around or whatever, which was very thrilling to me.

So that became the theory behind BEF’s ‘Music For Stowaways’ album. It was about how you could play your music and change your mood wherever you were. Basically, the Walkman liberated music. And there we were, at the sharp end with this cassette-only release. Lucky? Hey, no, it was deliberate! We loved the device, so we wrote some stuff specifically for it. The album was also partly inspired by Eno’s ‘Music For Films’. I’ve always liked the idea of music written for a purpose – for a film soundtrack, a theatre piece… I’ve always thought narrative was important.

The appearance of the Walkman also coincided with recording equipment getting smaller and more portable. We did have a studio, of sorts, but Ian [Craig Marsh] and I were more interested in the notion of going to people’s houses and being able to record ideas and then feeding those back in. It’s like we were interested in the popular technology as much as the popular music, so that first BEF album was like a holy triumvirate of art, music and technology.

‘Music For Stowaways’ came out in early 1981 and it included an instrumental version of ‘(We Don’t Need This) Fascist Groove Thang’. It was the first thing we did as BEF and it was just called ‘Groove Thang’ at that point. After being in The Human League, it was great to be able to use any instrumentation we wanted. It was enormously liberating. I love electronics, obviously, and I’ve always loved the concept of the futurist, but I was also keen to spread my wings.

And then along came John Wilson. That was a complete fluke on our part. We were in the studio working on ‘Groove Thang’ and we were quite happy with how it was going, but you’ve got to imagine what it sounded like before it had any bass or guitar on it. Anyway, out of the blue I said, “In this middle break, rather than some System 100 thing, wouldn’t it be great if it had a really cool bass solo?” and everyone went “What!?”. Then we sat down and thought, “Well, that’s all well and good, but we don’t know any bass players…”.

You’ve got to bear in mind The Human League were just three young lads from Sheffield in a room doing shit. We were yet to discover the world of session musicians. The only people we knew were the guys in other local bands… and most of them really weren’t very good. We’d just brought Glenn [Gregory] into BEF at the time and he was working at The Crucible in Sheffield as a stagehand, so I said to him, “Why don’t you ask if anyone there knows someone who can play bass?”. So he did and he found this 17-year-old lad called John Wilson. This lad said, “I play a bit of bass, but I’m not really a bass player”. But Glenn asked him if he could come down and try it out, just so we could hear what a bass would sound like in this section.

John was a really quiet guy. He was frighteningly shy. He came down to the studio with his bass, but he was left-handed so he was playing it the wrong way round, like Hendrix. We said, “We’re gonna count you in… One-two-three-four…” and when he started playing the solo, we were all looking at each other going, “This is fucking awesome”. Or words to that effect. We couldn’t believe it. So we’re going, “Erm, do you want to have a go at playing bass on the rest of the song, just to see what that might sound like?”. So he played bass on the whole song, which was just beautiful. Then when he was done he said, “I hope it’s alright because bass isn’t really my main instrument”!

When we heard that we said, ‘Soooo, what is your main instrument?’. And he said, ‘Well, I mostly play guitar’. We asked him where he lived and it turned out he was only 20 minutes away, so we said, “If we get a taxi, can you bring your guitar in?”. So he went and got his guitar and he ended up playing bass and guitar on the rest of the track. It was a bit like something out of one of those clichéd biopics where they say, “Son, you’re going to be a star!”. The guy was a virtuoso. That had never happened to me before and it’s never happened again, in 35 years of being in the music industry. We just got lucky. And every single bass player we’ve ever worked with since then, including a lot of very famous bass players, the first question they always ask is, “Who played bass on ‘Fascist Groove Thing’?”.

Where is John Wilson now? Dunno. I think he got stung a bit, he got ripped off. He started doing sessions for various people and someone refused to pay him. Some people can’t deal with the rough and tumble of the music business and I think he decided to go back to his bedroom. Rumour has it that he was extremely religious and he just went back to that world. Later on, he told us that his main instrument wasn’t really the guitar, it was actually the violin, but we never heard him play it. I don’t think we wanted to push our luck.