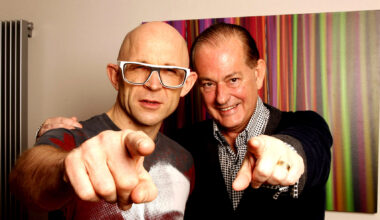

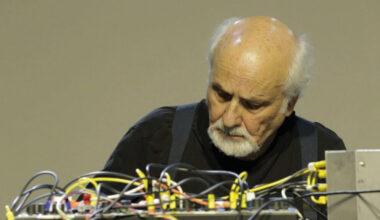

While he might be curating an online archive for his maverick Severed Heads outfit, Tom Ellard is not a man to rest on his laurels. “Don’t you want to jump full-bodied into the future?” he asks

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here