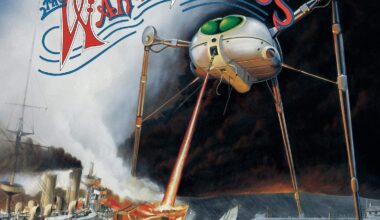

As the inaugural release on Brian Eno’s Obscure imprint, ‘The Sinking Of The Titanic’ has inspired generations of artists and listeners alike. Yorkshire composer Gavin Bryars reveals how he penned, or rather, “put together” this iconic composition

“‘The Sinking Of The Titanic’ is one of the earliest things I did. It’s certainly the earliest piece that I actually keep in my catalogue. I was a full-time jazz and improvising music-player until the mid-1960s and was feeling my way through. I’d been working with John Cage in America, so I was getting into that world of experimental music… but in actuality, I’d done very little.

“Right through the 1970s, I and my friends and colleagues in England were seen as almost unemployable in music departments, universities and conservatoires. We were sort of ‘dangerous’. How we went about things was not ‘musical’ in the way people understood it. But the places that did employ us were the art colleges.

That was a sympathetic environment.

“Quite a number of us working in the area of experimental music were using found music, found objects – rather like in the fine arts, with Marcel Duchamp and the ‘readymades’ – finding things to insert into an art context which you may modify to some extent or simply leave alone.

“With ‘Titanic’, I composed virtually nothing. I just put it together. The Latin verb componere means ‘putting things together’. It’s what composing means – not in the way musicians understand it, more in the way that a fine artist might, which is hard to define, and less commercial.

“In 1969, the initial idea for the piece was as a kind of audible conceptual art. It was first realised in December 1972 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Then it changed from time to time, because I was often finding new things.

“To begin with, there was extensive, very detailed and very precise research. I interviewed survivors, I spent time looking at the border trade report into the crash. I had diagrams of the ship and all sorts of nautical routes. I had the booklet that was given to all the first and second-class passengers about the ship and its facilities. I knew the complete passenger list. I knew the names of each musician of the string sextet, what instrument they played, where they were from and where their cabins were.

“When I was working on it, of course, the Titanic wreck hadn’t been discovered yet. It was a sort of mythic object at the bottom of the North Atlantic, somewhere about 500 miles off the Newfoundland coast. And that’s all we knew. We knew roughly when it went down. I had transcripts of all the radio signals, the morse signals between the various ships that were around… all those kinds of conversations. And then the critical question that started the whole thing off was, ‘What did the string players actually play?’. So the research took me quite deeply into that territory.

“There is a very reliable witness – the second wireless operator – who was actually in the water with a lifebelt around him, only 150 feet away from the ship. Obviously, he was concerned about getting dragged under by the suction, but in fact the ship slipped very gently under the water. He said the musicians were still playing and that they didn’t stop. ‘How they did it, I can’t imagine,’ he said.

“So that led me to this idea of the actual music moving under the water. The metaphor being that the musicians go, and with them goes the music, and the music continues… in this sort of metaphorical way.

“I dealt with questions as they arose. Sometimes they were conceptual or speculations which could get more and more absurd. But I followed them to their logical conclusions, which led me to some really crazy cul-de-sacs! Sometimes there were technical questions. For example, one of the things I did for the first performance was to work out what would happen to music underwater, if it could be played.

“I had a friend who worked at the physics department at Cardiff University in 1972. I went over there with tapes of the string group playing the music, and we made calculations about the degree of delay, of reflection and equalisation, all kinds of things that would happen as you descend. We made a sort of backing tape which lasted the length of the performance, where the music evolved into this increasingly murky state by applying the little formulae that my physicist friend had devised. I’m sure they’re laughingly inaccurate, but it’s poetry.

“I performed it in this way from 1972 through to the end of the 70s, including the recording for Brian Eno’s Obscure record label, and then I didn’t do it for a while. But later, I was persuaded to do a new performance for the Belgian label Les Disques Du Crépuscule, live in a water tower in central France. I was attracted to that for several reasons. One was the fact that it was a very strange kind of water environment in the middle of land. And secondly – more importantly – by then, the Titanic had been discovered.

“And there were details that changed – one thing, for example, was that a set of bagpipes was discovered on the seabed. So when I did the piece in France, I added a kind of bagpipe lament. It was quite a dramatic thing.

“One thing I got into with this was morse signals and the apparatus created by Guglielmo Marconi. When the rescue ship arrived in New York, apparently Marconi rushed up to embrace the sound engineer who reported it, because this was the first use of wireless telegraphy in ocean rescue. An hour-and-a-half after the ship sank, one ship heard the Titanic’s call signal. The ship was under the water – it was no longer there, but the sound was there still.

“Towards the end of his life, Marconi had this rather mystical idea – that once sounds are uttered they don’t disappear, they’re just smothered by other sounds around them. There was this crazy mysticism about it. Ideas about strange, speculative things… the mystery of it. The magic.”