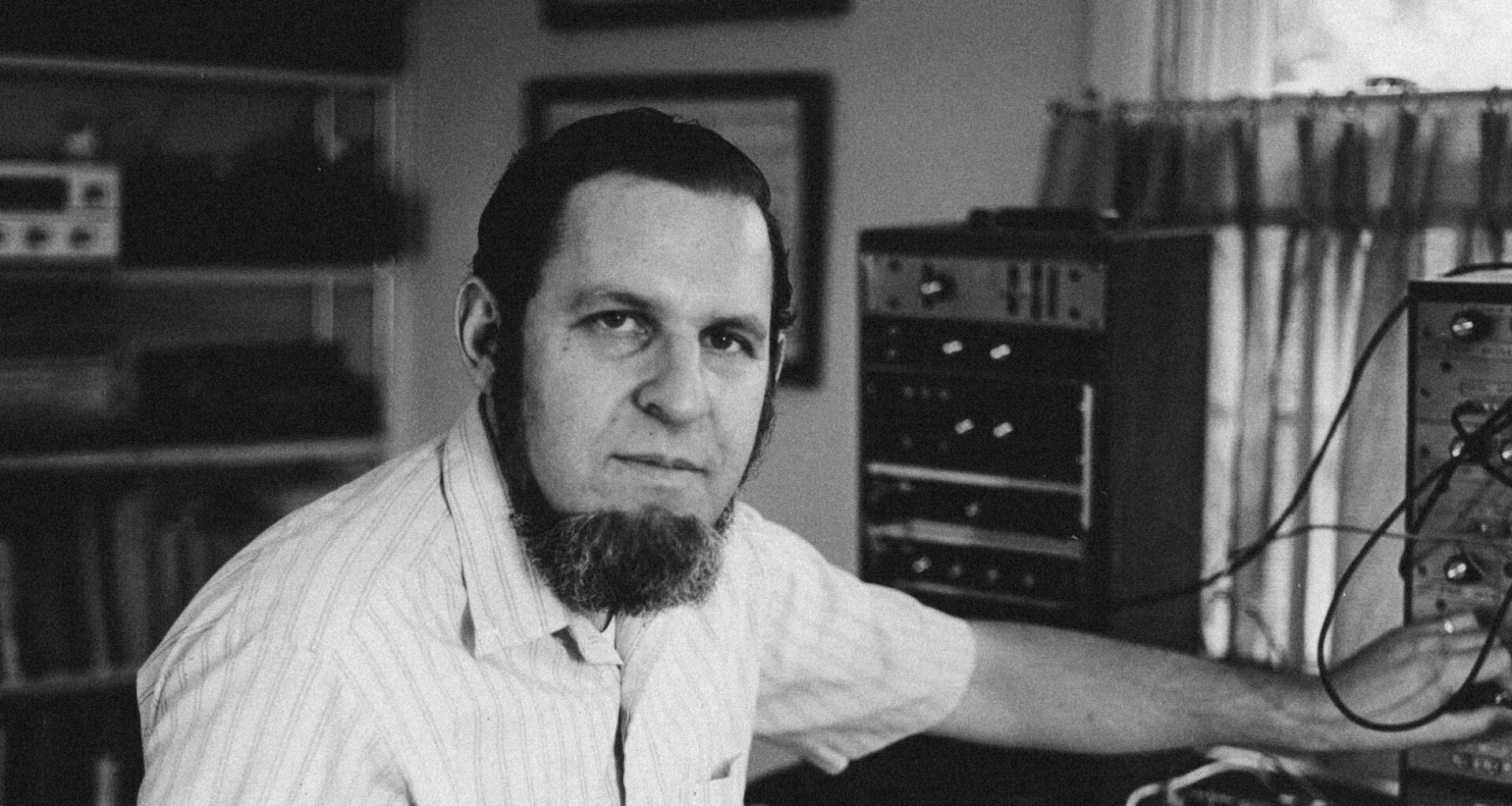

Moog collaborator turned university professor

The ticker tape machine that reported on the Flash Crash of 29 May 1962 didn’t stop spitting out paper until a good two-and-a-half hours after the stock market closed that day. Suddenly, $25 was looking like a fortune. To some it was more than a week’s wages. It also happened to represent the difference between the cost of the pre-assembled Moog Melodia theremin and the kit version that Herb Deutsch put together that year.

“I thought it was pretty straightforward from the directions, right up to the point where I needed the coils wound,” says Deutsch, the 88-year-old New York composer and electronic music pioneer. “I couldn’t do it, so I took it to a radio shop.”

After the fact, Deutsch decided to telephone RA Moog, the company that made the Melodia, for more information.

“I called and asked to speak to Bob Mooooog and, of course, being that I was on the phone with his wife and had pronounced their surname wrong, she quickly corrected me.”

Goodness knows how many times Shirleigh Moog had to go through that exercise. But despite this bumpy verbal start, Deutsch struck up an intense exchange with Robert Moog when he came upon him at the New York State School Music Association showcase in Rochester in the winter of 1963. He found the inventor alone in one of the convention rooms doing little, if any, business. He was ecstatic to meet the man behind his new instrument.

“I could tell Bob loved the theremin, but the biggest thing I took away from that conversation was when I mentioned ‘electronic music’. He wasn’t sure what I meant. The term had been around in the composition world for a while, but he wasn’t familiar with it.”

Herb Deutsch got hooked on electronic sounds after hearing the work bubbling up out of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in the late 1950s. The facility was home to the huge RCA Mark II Sound Synthesizer, aka Victor, which was kept in the same pleasant terracotta building that the university conducted nuclear testing for the US government.

Deutsch was studying at the Manhattan School of Music at the time, racking up a couple of advanced degrees before he began work as a teacher. He was a trained trumpet player, but his natural musical curiosity led him to experimenting with taped sounds and sine wave generators. The theremin, which he had read about in the hobbyist magazine Electronics World, was a natural evolution.

“I had to learn about what kind of attack you could get with it,” he says. “And that was something I definitely practised and worked on. I have a very good ear, so the pitch concept of a theremin came easily to me. The left-hand concept was more difficult because it was a new technique, but I picked it up fairly well. When she heard it, my wife Nancy immediately said, ‘This is an instrument that could be used in schools to teach ear training’. As it turned out, all the kids wanted to do was play scary music!”

While Deutsch and Moog initially bonded over the theremin, the time they spent working together at Moog’s first factory on East Main Street in Trumansburg, New York, in the summer of 1964 led to a wholesale rewiring of the music world. In less than half a decade, the “portable electronic music studio” they set out to build morphed into the most exciting instrument on the planet. The design behind the Moog synthesiser was accessible enough that it gave voice to the future in a way that the ideas of other engineers paddling in the same waters didn’t.

Deutsch would stay connected to Moog, sometimes in an official capacity, but his teaching and performing meant that composition stayed firmly lodged in the top ranks of his life. His 2012 compilation album, ‘From Moog To Mac’, closes with two pieces he had originally written for voice and piano, before he got the idea to score them for the theremin.

“They were two love songs that I originally wrote for soprano and piano,” he explains. “Then later, I thought the soprano voice would be more exciting if I wrote it for the theremin. The pieces could change more intensely in terms of harmony and rhythm, because the instrument can have a more dramatic sound than the human voice.”

To pilot the theremin, Deutsch recruited Darryl Kubian, a violinist with the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra. Following a single lesson with Lydia Kavina, a protege of Leon Theremin himself, Kubian had essentially taught himself to play the instrument over the following 10 months.

“The thing that actually pulled us together was when I splurged on this little Audi TT and I brought it down to Asheville for the Ether Music 2005 event,” says Kubian. “Herb loves sports cars, so that’s how we started our conversation. And then we realised how much we had in common musically. His youthfulness and the energy he has is amazing. You can’t help being drawn to him.”

Deutsch and Kubian recorded the two songs, ‘Longing’ and ‘Circling (You Did Not Know)’ at the latter’s home studio.

“He was probably in his early 70s at the time,” says Kubian. “I was on the floor with this diagram and Herb came right over and sat on the floor with me. Nothing seems to faze him.”

Deutsch’s five-year-old granddaughter Samantha, who sat in on the session, turned to Nancy Deutsch on hearing the theremin and said, “That sounds like someone singing!”.

“For a theremin player, you couldn’t get a higher compliment,” remarks Deutsch.

Deutsch has always looked for ways that the theremin would slot into his music. In 2005, an opportunity arose for him to debut his first piece specifically composed for the instrument, with a performance by the Children’s Chorus of the The Metropolitan Youth Orchestra of New York at the Lincoln Center.

“I thought that the sound of the theremin would be beautiful alongside the voices,” he says. “So I started thinking about a piece, which I called ‘Heard With Different Ears’. It was easy to write because you’re writing for what is basically a melodic instrument. You have to be concerned about the extreme high frequencies, how to handle vibrato, and take advantage of things like big pitch fall offs, like ‘Peeoooooooooooow’. But the real difficulty is always getting a good player.”

In this instance, it turned out to be Pamelia Stickney (formerly known as Pamelia Kurstin), the go-to thereminist in America at that point. Not only has she collaborated with avant-pop heavyweights like Yoko Ono and David Byrne, she was also heavily involved in the development of the Moog Etherwave Pro. She’s the woman seen playing for Bob Moog himself in Hans Fjellestad’s 2004 documentary ‘Moog’.

“I met Herb through Bob at a NAMM show,” recalls Stickney. “We stayed in touch and sometimes I would see him at concerts I was doing in New York. He reached out to me and asked if I wanted to play the piece.”

No recording of the performance is known to exist, but apart from being chastised by the director for kissing her boyfriend in front of the adolescent choir, Stickney says Deutsch’s piece was a joy to play.

“Back then, there were only one or two others who would approach me with written music,” she continues. “I was doing so much session work where I would show up and people would say, ‘We’d like to have a theremin solo on this track’. So it was either a case of anything goes or someone would hum something. But I remember Herb’s piece was well-crafted and had intention. It’s really nice when something very specific is being called upon in the writing. It’s good to be stretched that way.”

Because much of the terrain that Deutsch explored in electronic sound hadn’t been charted when he began his work, challenges of that sort were omnipresent. But throughout his career, his affinity for the theremin has remained a constant.

“I still have the one that I built in 1962,” says Deutsch. “I’ve not used it in many years, but I’ve kept it and replaced parts when I needed to. I’ve bought a couple of Moog theremins since then because, being a Professor of Contemporary Music History at Hofstra University, I was very excited about the instrument and its role in electronic music, which is pretty much all over the place.”

Bob Moog’s daughter, Michelle Moog-Koussa, who is now the Executive Director of the Moog Foundation, says her father didn’t often bring his work home with him, so Herb Deutsch wasn’t familiar to her when she was growing up. But over the past decade, she’s come to know and appreciate the extent of his creative spirit.

“Herb definitely thinks beyond conventional boundaries,” she says. “ One of his first compositions was in remembrance of the little girls that were killed in the Alabama church bombing in 1963. He’s very sensitive in that way and deeply connected to what’s going on around him in the world. I think that’s reflected in his work. Not only in the kind of compositions he creates, but in the instruments he chooses to use, which range from things that are hundreds of years old to modern-day synthesisers.”