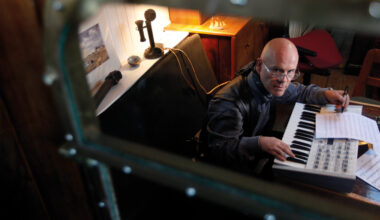

Learning the ropes from Stockhausen, La MoNte young and Terry Riley and showing the way forward to Eno and Byrne, Jon Hassell is an electronic music colossus. Seems that at 81, he’s just getting started

The exotic musical worlds that Jon Hassell inhabits are not visible on any map. In his long and winding journey from Memphis trumpet student to downtown New York City composer to free-floating citizen of the avant-jazz cosmos, He has been opening up new sonic territory for half a century.

Drawing from eastern and western styles, from northern and southern hemispheres, Hassell has pioneered a kind of techno-tropical fusion sound that blends futuristic and primitive, cerebral and sensual, acoustic and electronic.

Brian Eno and David Byrne were early collaborators, adapting Hassell’s revolutionary ideas, even if the results sometimes proved contentious. Later, art-pop icons including David Sylvian, Peter Gabriel and Björk enlisted Hassell to enrich their albums with his luscious ethno-jazz trumpet textures. More recently he has been embraced by left-field electronica artists, working with the likes of Carl Craig and Moritz Von Oswald.

Not many composers make their best work at 81, but Jon Hassell certainly comes close with his first new album in nine years. Glitchy and gleaming, sumptuous and cinematic, ‘Listening To Pictures (Pentimento Volume One)’ sounds like it was made by some ambitious young cut-and-paste digital collagist rather than an octogenarian veteran of the analogue jazz era. Like his enduring musical icon, Miles Davis, Hassell remains an omnivorous, forward-facing innovator.

Building on his existing relationship with the fabled British electro label, the new album is released on his own Warp-affiliated imprint Ndeya, which shares its name with the album’s softly undulating final track. He also plans to use the newly created boutique label to reissue classic works from his multi-decade back catalogue.

Derived from the art world, the album’s “pentimento” subtitle refers to layered re-paintings where traces of the previous work remain visible on the canvas. A keen collector of titles and concepts, even before the music exists for them, Hassell decided this term ideally encapsulated his sonic layering methods on the album.

“You put down one layer and then another layer on top,” Hassell explains down the line from Venice Beach in Southern California, his adopted home for over 30 years. “The touch-up becomes the painting in a way, and then there are things that poke through that layer. It was pretty much a perfect metaphor for dealing with these multi-track pieces. Just the idea of things showing through other things was very powerful. Like Natalie Cole singing with her father 30 or 40 years later, maybe that’s strange form of pentimento at work.”

‘Listening To Pictures’ also taps into one of Hassell’s long-standing fixations: the concept of “vertical listening”. This entails full sensory immersion in a piece of music, hearing what is happening now, not anticipating what happens next. This notion derives from the freeform jam sessions that Hassell used to perform with the avant-garde composer La Monte Young.

“We were doing these two or three hour tune-ups basically,” Hassell recalls. “Sometimes it would just gel when everybody was on that frequency, and this angelic chorus of overtones happens – many images converge and you just get this strong feeling, that’s what I meant by vertical listening.”

Born in 1937, Jon Hassell grew up in Memphis during the pre-Civil Rights era. Despite his white middle class background, his early musical education included African-American juke joints and the “deep roots blues” of the Mississippi Delta. Which may help explain his enduring fascination with musical styles more often associated with the global south.

The progressive jazz pioneer Stan Kenton and Peruvian-born exotic pop queen Yma Sumac were early passions for Hassell. Later, Miles Davis became a key guiding influence, helping to shape not just his trumpet-playing style, but also his restlessly experimental attitude. Hassell even went on to commission several album sleeve designs from Mati Klarwein, the German artist most famous for Miles classics including ‘Bitches Brew’ and ‘Live Evil.

In the mid-60s, Hassell’s musical journey led to collaborations with some of the founding fathers of the 20th century avant-garde. While studying in upstate New York, he joined La Monte Young’s Theatre Of Eternal Music and played on the original recording of Terry Riley’s milestone minimalist work ‘In C’. He also spent two years in Cologne studying under Karlheinz Stockhausen, where he shared a class with future Can founders Irmin Schmidt and Holger Czukay.

On his return to New York, Hassell created an “invisible sonic sculpture” called ‘Solid State’, an early experiment in analogue Moogtronica whose tones were time-sculpted using voltage-controlled filters. Completed in 1969, the piece was performed live several times over the coming decade.

“That was done in the really early electronic music studios with a bank of Moog oscillators,” Hassell recalls. “It was a response to being in New York and being with Terry and La Monte, I was obviously influenced by them. It’s like a big block of sound that the sequencer cuts holes in rhythmically. That’s definitely one where the idea of vertical listening comes in very strongly, the harmonic layers element is there. There is nothing much of surprise there so you fixate on the overtones and the holes that have been cut out to make them audible.”

In the early 1970s, Young’s wife Marian Zazeela introduced Hassell to Pandit Pran Nath, a Pakistani-born maestro of the meticulously precise Indian classical singing style Kirana gharana. Hassell studied obsessively under Nath and still cites him as a key influence in opening up his mind to new musical philosophies. His signature “conch shell” trumpet style, typically couched in the “electronic eye shadow” of digital delay, partly grew from his attempts to replicate the delicate dynamics of Indian raga singing.

Hassell also credits the liberating influence of soft drugs and psychedelics on his musical awakening around this time. While studying with Nath, hashish milkshakes and marijuana-laced ladoo almond sweets were part of his daily diet.

“The whole thing was coming out of drug culture in a way,” Hassell says. “Of course, it’s easily corrupted and it becomes a cliché, but that whole era of Timothy Leary – tune in, turn on, drop out, all that kind of thing – there was something going on then that was very much needed. It was a way of escaping the torture of being lost in logic and the way the world is set up on certain levels. That was like the giant of the north struggling with the giant of the south in a big tug of war.”

Hassell’s theories about a global north/south divide have shaped much of his creative career. He decries the “cultural racism” that holds music from colder northern societies in higher regard than music from the southern hemisphere, creating an artistic hierarchy which elevates arid intellectual abstraction over more rhythmic, communal, spiritually uplifting forms. He recently completed a book-length version of his thesis, ‘The North And South Of You’, many years in gestation, but now finally looking for a publisher.

“In northern climates it is cold, you’ve got to keep moving, you have to think of things to do indoors,” Hassell explains, giving me a TED-talk soundbite summary of his grand theory. “So it developed in a different way than the people who stayed in the south and invented dances and picked food off the trees. That led to the northern mentality, and of course the northern mentality took over and ruled.”

As he began to carve a career as a trumpet player and composer in mid-1970s New York City, Hassell crystallised his theories into the concept of “Fourth World” music. This snappy term was rooted in a compelling counter-factual fantasy of the “coffee-coloured classical music” that might have arisen if geopolitical history had taken a less Eurocentric, north-dominated, colonialist path.

Hassell put this theory to work on his early albums, pan-global collaborations that fused antique tradition with high-tech studio sonics, samplers and sequencers. He worked with Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos, Senegalese drummer Ayibe Dieng, Moroccan musicians from the gnawa Arabic spiritual tradition, and many others. This was music from everywhere and nowhere, both ancient and modern, organic and synthetic.

Cultural cross-pollination has remained a recurring motif throughout Hassell’s career, though he hesitates to call it a manifesto.

“It’s not a catechism to follow or anything, it’s just a way of defining what’s going on,” he explains. “It’s really about discovering the rest of the world. The way I’d describe Fourth World is a kind of tasteful embrace of what is. And taste here means not leaving the spice off the table, right?”

Hassell’s Fourth World idea found an enthusiastic champion when Brian Eno arrived in in New York in 1978. Fellow late-night party animals on the fringes of the post-punk art rock scene, the duo first ran into each other at the downtown performance space The Kitchen. Eno was serving as producer to Talking Heads at the time, and recruited Hassell to play on the band’s seminal 1980 ‘Remain In Light’ album.

Eno and Hassell then worked together again on their joint album ‘Fourth World Music Vol 1: Possible Musics’, which served as a kind of sonic blueprint for Eno’s next Byrne collaboration, the avant-world collage of ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’.

“He and David Byrne were hanging around,” Hassell recalls. “I was turning them onto the Ocora label, the French early world music label. Out of which came ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’, which I was originally involved in, but it wasn’t really going where I wanted to go.”

Hassell is being unusually diplomatic here. Although ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’ was initially conceived as a three-way collaboration, he dropped out after hearing some initial demo tracks that he disliked. He later dismissed the finished album as “a not-too-subtle appropriation of what I was doing”, publicly criticising Eno and Byrne for their “toxic” rock star arrogance. Nowadays he is more conciliatory, conceding his own stubborn attitude may have played a part too.

“I did some little cassette things for the album, and then they went off to LA to the studio,” Hassell says. “I was in New York, we were all living in New York, and what I got back from them was just too poppy for me at that point. If you had to slice it in one direction, I was more on the jazz side and they were more on the pop side. I made some errors in terms of saying I really didn’t want anything to do with that. I think it could have pushed things in another way that was more me. But then it would probably not have been a gigantically successful record, ha!”

Despite his bruising brush with the celebrity art rock world, Hassell’s association with Eno and Byrne undoubtedly helped open the door to more mainstream projects in the 1980s and 1990s. He became a serial collaborator, playing with the likes of Peter Gabriel, David Sylvian, Tears For Fears, Ry Cooder and Björk. He largely dismisses this period as the music industry embracing a cosmetic trend for global fusion sounds.

“I was just doing overdubs,” Hassell shrugs. “It was part of the temperature of the moment, but it’s probably not worth calling it a collaboration. There was already a consciousness of what I was doing. I’d been to that territory first, so it wasn’t like I was being educated by them in any way.”

By the early 1990s, Hassell was forging ahead again, sampling Public Enemy and commissioning remixes from he likes of 808 State. Hip hop beats and ambient electronic textures figured prominently in his ‘City: Works Of Fiction’ and ‘Dressing For Pleasure’ albums.

“A lot of early hip hop really enchanted me,” Hassell explains. “It was technological African in a way, the African spirit moved over to New York and beatbox technology. That was such a beautiful culture, related spiritually and culturally to Africa.”

While Hassell’s experiences on ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’ created bad blood between him and Eno, the hurt eventually healed.

“I owe a lot to Jon,” Eno wrote in The Guardian in 2007. “If I had to name one over-riding principle in Jon’s work it would be that of respect. He looks at the world in all its momentary and evanescent moods with respect, and this shows in his music. He sees dignity and beauty in all forms of the dance of life.”

Preferring to forgive, but never quite forget, Hassell describes Eno’s early sleights against him as a “brotherly transgression”. The pair have worked together many times since and are close friends again. Fellow ambient godfathers, veteran explorers of the Fourth World.

“Yeah, we are,” Hassell chuckles. “It’s a good thing to leave it a while. It is brotherly in a way. It’s as if your brother married your girlfriend and it took two decades to get over it. But I’m godfather to Brian’s daughters, and we’ve actually had a very close connection recently. I guess as we head towards the exit door of life, it becomes a hand-holding moment.”

‘Pentimento’ is out on Ndeya