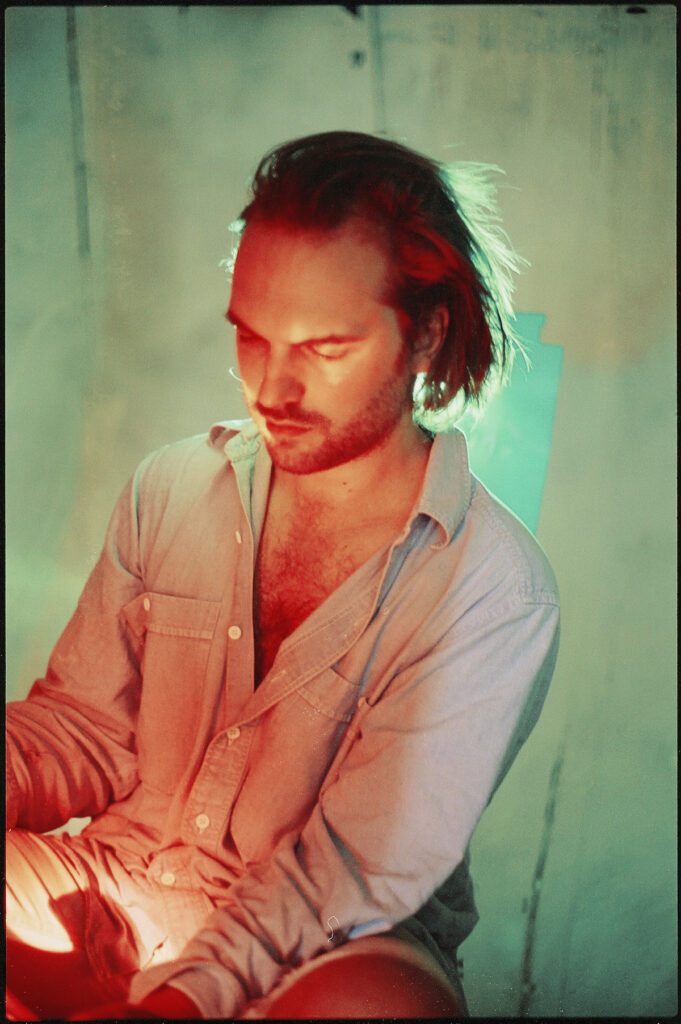

Sam Eastgate reveals how paranoid lizards and an addiction to moss, as well as a homemade “human drum machine” called GENE, have all fed into his latest LA Priest record

Sam Eastgate has always seemed to exist in a world apart from his prescribed peers. His breakthrough band, Late Of The Pier, were initially lumped in with the glitzy neon of the new ravers, but they made an awkward fit with a short-lived and London-centric scene running on coke and Klaxons.

Formed in the Leicestershire market town of Castle Donington, LOTP’s unique sound – a sort of unhinged electronic dance prog – was more due to their mindset than a place on a map. Aesthetically, they left their own mark too. The video for their single ‘The Bears Are Coming’ documented a sort of twisted, shamanic, tribal death march, but finished with the band chewing flumps. Their acclaimed album ‘Fantasy Black Channel’, released in 2008 on Parlophone and produced by Eastgate and Erol Alkan, was a gorgeous cacophony of Numan-esque synth sounds, frantic guitars and sawtooth subs. It was LOTP’s first and also last album. Job done, at least in their eyes.

While ‘Fantasy Black Channel’ is on its way to bona fide cult status, Sam Eastgate views this period as just one step in a life that has revolved around sonic explorations. These days, operating under the moniker LA Priest, you’ll still find him set apart, holed up in the North Wales countryside with a shed full of moss (we’ll get to that), building new instruments and pondering audio experiments.

“I started to get fascinated with electronic equipment when I was about 10,” says Eastgate. “A few years later, my family were about to move house and we decided to bury a time capsule. I put a design for a synthesiser in there. That was what I was obsessed with. It’s crazy to think, but I’d had access to a few synths my dad had and I was adamant that I knew how to design something better.”

The young Eastgate initially planned to send his designs to Moog, under the youthful assumption that they’d be thankful for his innovative suggestions. Alas, this did not come to pass, but a career as a musician clearly beckoned.

“Everything I’ve done since then is just me going, ‘Am I going to make an instrument?’, ‘Am I going to make an album?’, ‘Am I going to discover some cool technique to get sound from something?’,” he says. “I don’t think we’ve discovered how to sonify the world around us as much as we could. There’s a lot more sound we can extract.”

The word “sonify”, meaning to enhance by adding music or sound effects, isn’t recognised by spellcheckers, which neatly demonstrates the depths of Sam Eastgate’s ambitions. Following Late Of The Pier, he spent time working with psych-funk misfit Connan Mockasin as Soft Hair. The pair travelled the world, documenting electromagnetic phenomena in Greenland quarries and recording a concept album about a lizard race fearing a disease that turns them human.

In 2015, Eastgate released his first LA Priest record, ‘Inji’, a soulful, funk-laced collection that drew comparisons to Prince and Ariel Pink. But it’s the recently issued follow-up, ‘GENE’, that feels like the true arrival of LA Priest. Named after a drum machine he designed and built himself, ‘GENE’ sews together the myriad threads of Eastgate’s creative life.

“I started this record back in 2016,” he says. “I was at the stage where every time I picked up a guitar or a keyboard, I was just repeating the same rhythms. I wanted a machine that would throw me off or force me to bend to the shape of its sound. I just didn’t know a drum machine that would do it the way I imagined. The original thinking was that you need a drum machine to be better than a drummer, straighter and more consistent, with every beat the same. So I walked around the fields near my house thinking, ‘How do you get the beat you want out of it?’, ‘How do you get a beat to be late, but the next one to be early?’, ‘How can you mess with the time signature as you go along?’.”

When he eventually cracked it, at least in theory, Eastgate duly ordered the components and gradually assembled them in a spaghetti of wires, solder and circuitry. He called the result GENE.

“I never refined it too much,” he continues. “I just made it work ‘enough for rock ’n’ roll’, as they say. It’s the same with all my instruments. When I’m on the road, I often get stagehands holding up my guitar and being like, ‘This looks like it was made by a three-year-old!’. I understand where they’re coming from, but from my perspective, if you just fall slightly short, you’ve got an imperfection that could add personality to a track.”

Perhaps due to the success of the design or perhaps because he’d poured so much of himself into it, Eastgate’s “human drum machine” had the character he needed and quickly proved a valuable sparring partner.

“I started recording with it as soon as I had a basic bunch of wires and it all went on this new album,” he explains. “The last song, ‘Ain’t No Love Affair’, was actually the first thing I did with GENE and it is almost on there as a point of historical record. It’s probably the roughest track because there are a lot of sounds I didn’t manage to keep in the final version of the machine. When you put it into a box, you can’t use every wire in the same way you can with the first build.”

Once GENE had been wrangled into a box, ‘Beginning’ and ‘Monochrome’ soon followed. These two songs are wildly different, the former a Prince-ish link to Eastgate’s ‘Inji’ material, while the latter has a percussive push and pull, spliced with recordings of rain and a reedy synth that sounds part string, part huge wind instrument. Both tracks are heavily indebted to GENE’s magic.

“That’s the beauty of GENE and that’s why I named the album after it,” notes Eastgate. “It’s not a record about a machine, but the machine is injecting a lot of heart and soul into it, or some part of the interaction between me and the machine is providing that soul and human warmth.”

It’s that sweet spot, much sought after by electronic musicians, where Eastgate seems to thrive – the in-betweens and ambiguities of the natural and mechanical worlds. It’s why the greenery of his home in Montgomeryshire in North Wales appeals to him. It’s far removed from the oppressive urban environs so stereotyped in electronic music circles.

“I’m always caught between making songs that reflect the sounds of the environment I’m in and songs about people or interactions,” adds Eastgate. “There’s some crossover there, but I feel I sway from one to the other. It’s a grass is greener thing. I’ve written a lot of songs in cities where I’m imagining getting away from that, but then I’ll sit in the countryside and write about conversations with people I can’t see because I’m so far away.”

Eastgate’s Soft Hair project was born of both town and country, conceived between the deprived St Ann’s estate in Nottingham and a coastal studio in New Zealand. Eastgate had met Connan Mockasin at a party in 2007, following a disagreement involving a stolen fibreglass pig. A year later, they had not only patched things up, they’d bonded and co-created an imaginary world. The central concept of the pair’s eponymous album was that a cold, sad, soft-haired hybrid lizard race was dealing with a virus that made them human – their greatest fear and therefore the source of much paranoia.

The current preoccupation with viruses and paranoia are less important to Eastgate than the tone of the world that he and Mockasin created. It was a sort of coping mechanism for their inner lost sociopaths at a point when neither of their musical careers seemed on the up. Again, it was the duality that interested Eastgate.

“It was all about this weird place between comedy and tragedy,” he says. “The idea that this creeping sadness they prized was melting away was completely hilarious to us. We thought it was so funny that these characters couldn’t get a break and they were always paranoid. We’d both known people like that. You feel sorry for them, but you also want to laugh, because they’re always paranoid, always trying and failing, but not trying enough. And I think it’s healthy to recognise that in yourself as well. It helped us both at a time when we had these big ambitions and we wanted to make all sorts of things happen. When they didn’t work out, it was easier to laugh about it.”

For all its in-jokes and intellectual heft, the true benefit of ‘Soft Hair’ seems to have been in examining the line that art can offer between two worlds – the human and the lizard, the tragic and the comic. Eastgate talks about the film ‘Chinatown’ as the perfect balance that leaves you “watching in disbelief”.

“Once you’ve got a taste for that, it’s hard to watch a soap opera, which is just meant to make you feel one emotion at a time, whether it’s worried, or sad, or elated,” he notes. “I would be the one who was laughing at people’s misfortunes on soaps and people who watched them seriously would be like, ‘Don’t! This is really bad! Jeremy’s got to have an operation now!’.”

It’s not necessarily about maturity, or high art versus low. It’s more a plain dislike for the patronising and the predictable.

“The stuff I’ve done since Soft Hair is less often straying into joker-esque territory,” explains Eastgate. “With Soft Hair, it was always pushing you around emotionally, but I’ve now found it more refreshing to be quite sincere. I’m not trying to tug on the heartstrings. Some songs are simply singing a mantra and some of it is just dance music, in the sense that it’s not all about the intellectual side.”

That physical response to music is one of the reasons he fell in love with electronica at a time when every other Middle England kid was squeezing into skinny jeans and trying to learn the guitar riff from The White Stripes’ ‘Seven Nation Army’.

“I like music that doesn’t have any storyline,” says Eastgate. “What interests me is when there is an emotion attached and you don’t know where it’s coming from. I think I was 10 when ‘Homework’ by Daft Punk came out and it was the biggest thing for me. I later wondered how I got this injection of emotion from it. It couldn’t just be the thump-thump-thump that made me feel the highs and the lows. The little melodic bits and the sound textures, there’s a wizardry to that, and I don’t think a lot of people really understand how it works. You have little chemical reactions in your brain that are some weird by-product of something you’re hacking into. That’s what’s clever.”

He’s less motivated to create highfalutin concept records these days, although he doesn’t rule out a return to Soft Hair, but he still wants to understand the option of the “third sound” with ‘GENE’.

“I’m trying to do it with the instruments I have on hand,” he notes. “Sometimes it’s just the way the guitar and the synth clash with each other. Like on ‘What Moves’, the main single from the album. The thing that excited me with that song was how I put the guitar and the synth down and it sounded like there was a vocal harmony in there. You could hear this ghost voice, which only happens when you have a lot of subtlety in there. I find that fascinating.”

Like every musician worth your time, Sam Eastgate is impossible to really pin down. But that’s what makes stepping into his world so exciting. With LA Priest, his shifting obsessions seem to all find a way to work together. His shed full of moss, for instance, came about from rambles in the forests near his house, but the moss wound up in some of his videos, as well as adorning the cover of ‘GENE’.

“I felt like I could do everything with moss from now on,” he laughs. “I don’t know if it’s the humidity or the oxygen in some of the forests where it grows, but it’s like a drug or something when you get higher up. You don’t want to come down from the clouds. Literally. I got addicted to moss, basically.”

The explorations and obsessions that have always been a big part of Eastgate’s world will, it seems, continue to dominate his life as LA Priest.

“I’m never really looking for a single thing,” he reflects. “The harder you work, the more you experiment with sound and music, the more you realise how much there is to explore. I’ve realised that if I don’t try to do as much as I can before my time on Earth is over, I’m going to have barely scratched the surface.”

‘GENE’ is out on Domino