In his new book, ‘Mars by 1980 – The Story Of Electronic Music’, journalist, author and Electronic Sound contributor David Stubbs charts the evolution of those music makers who prefer dials and diodes. It’s a highly personal account that sort of starts with Francis Bacon’s utopian text ‘New Atlantis’ in 1626 and kind of ends up with Skrillex. In this exclusive extract, Stubbs explores the legend of Kraftwerk and explains how, despite not having a substantial release since 1986, they remain so utterly vital…

By the mid-1970s, among the most enthusiastic fans of Kraftwerk’s ‘Autobahn’ were DJs in Detroit, the Motor City. From the early 1980s onwards, it became abundantly clear that young black musicians were the new Futurists, just as white rock and its audiences were about to enter into a long, post-modern period of conservative retrospection. This made sense, of course. Whereas white audiences could hark back wistfully to the earlier decades of the 20th century, perceived through a halcyon gauze – more innocent, purer times – black people had no reason to feel any fondness for those decades, the experiences of their immediate ancestors scarred by Jim Crow, segregation, and every kind of indignity and injustice. The present wasn’t so great either. But the future? Maybe.

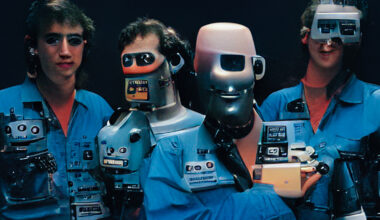

This perhaps explains why, since the electro-funk of the early 1980s (and preceded by dub), black artists have been responsible for so many of the rewirings of pop, from hip hop through to drum ’n’ bass, grime and a host of subsidiary developments. Roboticism was parodied and, in a sense, reclaimed from its slave implications in the stiff, improbable motions of body-popping and the moonwalk.

In 1986, it was techno, led in Detroit by artists like Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May, who asserted to the writer Kris Needs in 1990 that “It comes from the theory and the theme of advancement, from the technological revolution which is known in Alvin Toffler’s book [‘The Third Wave’] as the ‘third wave’ of technology”. May openly acknowledged that Kraftwerk were the progenitors of techno, but also said, “The biggest joke is to see an Italian or Belgian or English record and they’re called techno”. To him, for white Europeans to lay claim to this music was as absurd as Kenny Ball or Stéphane Grappelli claiming to have invented jazz. The black primacy of techno was now a given. This was music reduced to its metal essentials, like the robot Maria’s flesh burned away in ‘Metropolis’ to reveal the workings of her machine nature.

Today, there is such a thing as a Museum of Techno in Detroit. Just a block or so away from the Motown Museum, it’s situated in a former union hall acquired by Underground Resistance back in 2002. Among its exhibits are images of Leonard Nimoy (Spock in ‘Star Trek’), George Clinton’s P-Funk project, with whom Clinton dared to invite the public to “conceive of a nigga in a spaceship”, and the cover to Kraftwerk’s ‘The Man-Machine’, as well as a room full of the electronic hardware that launched Detroit techno, an engine room of keyboards, synths and 808 and 909 drum machines. There is also a larger item: a lathe used to master those early vinyl recordings, built back in 1939 and resembling, according to one newspaper article, “a giant Art Deco sewing machine”.

Ironically, just as Detroit techno was being birthed in 1986, Kraftwerk were about to wind themselves up as a recording force. No one was to know it at the time, but ‘Electric Café’, released that year, would be their final album proper. They have spent the last 30 years or so issuing vague promises of new material, the odd remix album and, in December 1999, the single ‘Expo 2000’. The 21st century tour circuit is choked with superannuated megasaurs filling the O2 night after night and plying audiences with the hits of yesteryear; it’s easier to list who isn’t at it (ABBA, The Smiths) than who is (everyone else). And yet even if only in the form of solo releases, at least these acts have made token appearances in the studio to add to their catalogue, despite the cries of their audiences to party like it’s 1972. Kraftwerk, however, have left their futurism long behind them. From a creative viewpoint, this band, just a few years short of celebrating its half-century, was only operative for 12 years – 1974 to 1986.

There was a reason they deprogrammed that year; in fact, ‘Electric Café’, for all its graphic brilliance and impeccable assembly, may even have been an album too soon. For by 1986, their man-machine project was done. They were victorious. Their use of synthesisers no longer marked them out as novel, inhuman, effeminate, inauthentic, Teutonic, fleshless, deadpan provocateurs. Synthesisers were ubiquitous in 1980s rock. Their warm sheet waves acted as an FM lubricant for everyone from Van Halen to Bruce Springsteen (‘Dancing In The Dark’). Yes, even Springsteen, rock’s very own woodsman and impassioned yearner for the human touch, the anti-Hütter, was freely using synths. From funk to jazz fusion, light pop to heavy metal, synths were as quotidian as computers in the workplace. So when Kraftwerk ominously vocoderised the words “industrial electronic sounds” on ‘Musique Non-Stop’, far from being confounded or making bad Hitler jokes, the world simply said, “Yes, we know”.

Like Rotwang creating the doppelgänger of Maria in ‘Metropolis’, pop had added flesh and blood and warmth and obvious soul signifiers to synth-based pop. Only this wasn’t an attempt to subvert or create insurrection – the 1980s popsters were synth-cere. It was no longer a Meccano affair, all its workings exposed. A prime example was the Eurythmics, with their debut single, ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’. In the manner of Alison Moyet of Yazoo and others, Annie Lennox emoted in waves over Dave Stewart’s bed of synth. They could cultivate an air of froideur, immobility and androgyny in the video, but this melted the moment Lennox unleashed one of her trademark sub-Aretha wails. This would become a formula for 1980s pop, one that was reminiscent of Derek Smalls in ‘Spinal Tap’ describing his guitar colleagues like “fire and ice” and himself as the mediator between them, “like lukewarm water”. With its envious fixation on Real Black Music, mid-to-late 1980s electropop, from Bronski Beat to George Michael, would flood the airwaves with so much lukewarm water as it hastened towards the passion revue that was Live Aid.

1986 was also the year in which analogue was at its lowest ebb; all was now digital. So much so that Bob Moog discovered that the rights to his name, which he had sold some years earlier, had expired due to lack of use. Who needed Moog? Who needed analogue? It would fall to a newer generation – not just May, Saunderson, Atkins and co, but also A Guy Called Gerald and the first British acid wave – to strip back electronic music to its Kraftwerkian bare metal essence.

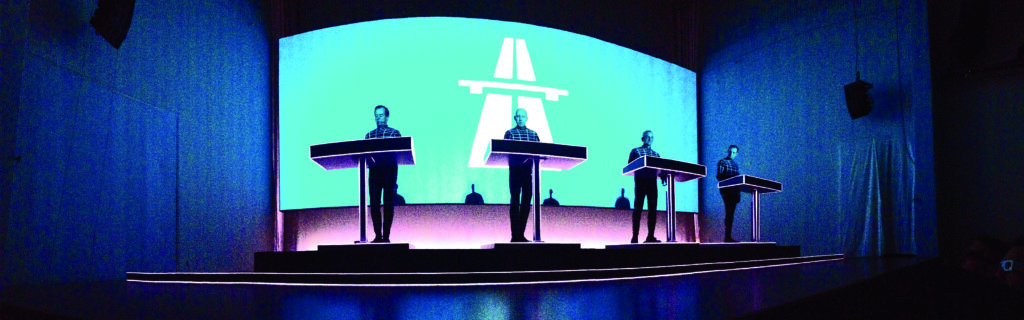

Today, then, Kraftwerk are the most supremely nostalgic of all bands, dedicated solely to their legacy, their creative additions all in the stage presentation, which is now a truly state-of-the-art visual bombardment of retro-futurist kitsch, from the 1980s-style green glow of their graphics and fonts, to sweeping, digitally colourised cycling footage projected on previously unavailable wide screens, to reproductions of the ‘Autobahn’ artwork; it’s one long futurist flashback which only now do they have the technical visual wherewithal to put on. This has been required to realise Kraftwerk ultimately as a pop Gesamtkunstwerk. Footage from the group in their heyday shows the contexts in which they were forced to play as leaving much to be desired, despite their own best sartorial efforts and onstage arrangements – glum, brown-panelled, all-purpose concert halls, as well as abysmally dated pop videos. The music they barely tamper with, but the visuals are now what they might have hoped for or come up with 40 years ago, as they contemplate their small, perfectly formed body of material over and over.

What is it that draws music lovers to Kraftwerk’s live shows, though, beyond the consoling and enhanced spectacle of the 20th century familiar? Perhaps it’s because despite all that has developed as a result of them, and the fact that they have long lost their tag as the only electronic players in town, they remain, in a deeper sense, the most electronic pop group who ever lived – an ideal, a pinnacle, an extreme. No one has outdone them in this respect. Everyone else is just a bit too humanly deviant. They exceed everybody and everything else. Conceptually, their very bodies, their very selves, are wired up and into the Kraftwerk entity. Of the four original members, only one remained in 2018. They are generous employers – not for them the utilitarian glumness of a single sallow player hunched over an Apple Mac – though their employment policy could be criticised for being non-inclusive. However, who is to say that one day, when its members go the way of all flesh, Hütter included, Kraftwerk will take on new members – women, ethnic minority, transgender or even man-machine hybrids as yet unconceived?

And could it be that when Kraftwerk intoned, “We are the robots”, the shock they created, and forced rock critics to absorb, lay in their declaration of an oblique solidarity with the hitherto put-upon not-quite-humans who had endured so much for so long? Hence the natural connection with African American music and culture, from body-popping to electro-funk and techno, as well as compliments such as Carl Craig declaring that Kraftwerk were “so stiff, they’re funky”. As white and male as they come, Kraftwerk were anti-white and anti-male in ways that mattered. For years, I misheard the opening lyric of ‘Robots’, “We’re charging up our batteries”, as “We’re charging on to victory”. Kraftwerk did charge on to victory. It’s a victory we still have to deal with.

‘Mars By 1980 – The Story Of Electronic Music’ by David Stubbs is published by Faber & Faber