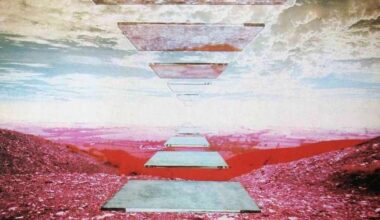

Shackleton’s stock has never been higher. In a rare interview, the sound designer and arch-collaborator opens up on his gloriously hypnotic new album, a disorientating miasma of woozy hauntology and “cracked-mirror oddness”

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here