We trace how musique concrète mutated from turnable experiments in the 1940s to turntable experiments in the 21st century via audio tape and sampling…

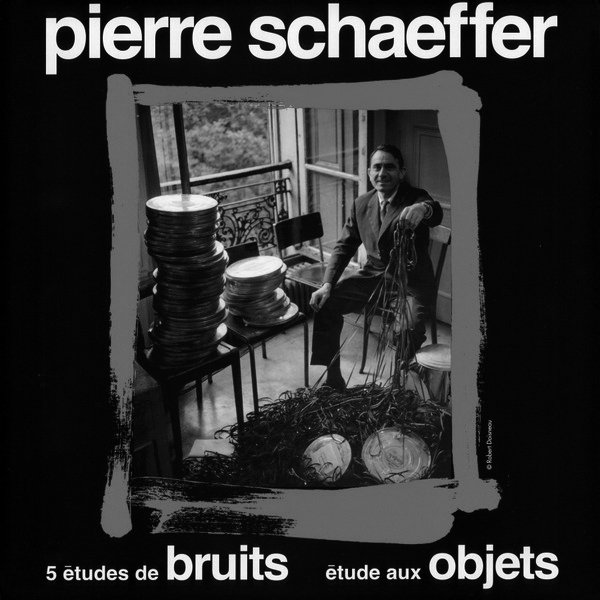

Pierre Schaeffer: ‘5 Études De Bruits’ (1948)

Pierre Schaeffer broadcast his five pieces made up of “objets sonores” (sound objects) in October 1948. This was before tape was readily available, and so the pieces were put together using turntables and a cutting lathe in what must have been an incredibly laborious process. Sounds on discs were played backwards, put through filters, envelopes were altered using volume controls and he was able to cut locked grooves to loop certain sounds. The pieces were played live with four turntables and the resulting mix of sounds was cut live direct to disc using the lathe for the final versions. The most celebrated of the five pieces, perhaps because of its perceived influence on Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans-Europe Express’, is ‘Etude Aux Chemins De Fer’, which was made up of sounds recorded at a train station. Schaeffer didn’t call what he doing musique concrète until the following year.

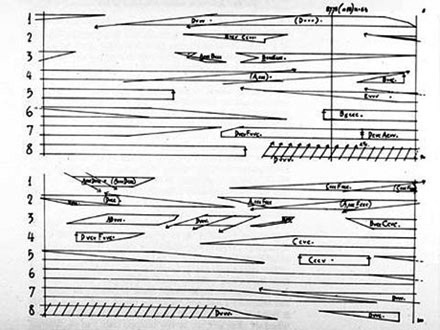

John Cage: ‘Williams Mix’ (1952)

This piece was put together in New York with the help of Louis and Bebe Barron, whose electronic studio was a draw to many avant-garde composers, not least because it was the first private studio in the USA to own a tape recorder. The four-minute ‘Williams Mix’ was a rapid-fire collage of snippets of voices, frogs croaking, and all manner of electronic noise, recorded by the Barons over a nine-month period of intensive work. The first performance took place in 1953 at a concert of contemporary music at the University of Illinois, and it wasn’t made commercially available until the release of a triple vinyl mono boxset in 1959 called ‘The 25-Year Retrospective Concert Of The Music Of John Cage’ (which itself took place in New York’s Town Hall in May 1958). The audience reaction is something to behold, a literal shouting match between a chunk of people booing versus enthusiastic cheering and applause by those impressed by this glimpse of the future they’d just heard. The fact that in 1958, Cage was holding a retrospective is somewhat astonishing, but then he had been experimenting with sound, including some very early turntable work, since the 1930s.

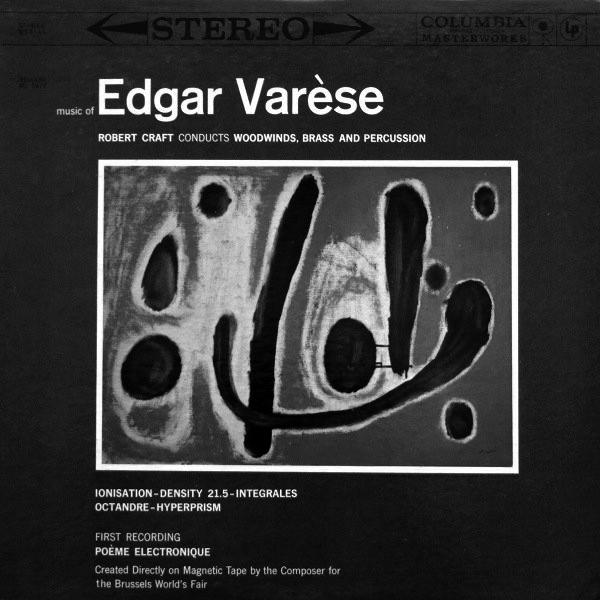

Edgard Varèse: ‘Poème Électronique’ (1958)

This was probably the most widely heard piece of musique concrète in the world until The Beatles’ ‘Revolution 9’ a decade later. At just over eight minutes, the piece was commissioned for the Philips Pavilion at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels where its clanging bell introduction, which gives way to woody thuds, unearthly wails and tightly edited electronics, was played through a 350-speaker audio system on a loop in a space-age building designed by Le Courbusier. It was first released in 1959 on the album ‘Memories Aux Bruxelles’ on the Carlton label, which was a cheap souvenir record of music from the various pavilions at the World’s Fair, credited under the name ‘Electronic Music From The Netherlands Pavilion’. Varèse’s incredibly important composition didn’t get a decent release until 1960, when it was put on the album ‘Music Of Edgar Varèse’ on the Columbia Masterworks label.

Pierre Henry: ‘Orphée’ (1960)

Pierre Henry, while at the RTF studio, had worked on music for the “concrète opera” ‘Le Voile D’Orphée’ with Pierre Schaeffer. It was performed live in 1953 at a festival in Germany where its loud tape music segments, played over speakers, freaked out the concert goers. Henry quit the RTF studio in 1958, having had enough of what he felt was Schaeffer’s overbearing and inflexible approach and set up a makeshift studio at his parent’s house. He continued what would be his long career as one of France’s most celebrated modern composers with this 1960 recording that saw Henry return to the Orpheus myth to produce an impressive concrète soundtrack for the choreographer Maurice Béjart’s ballet company.

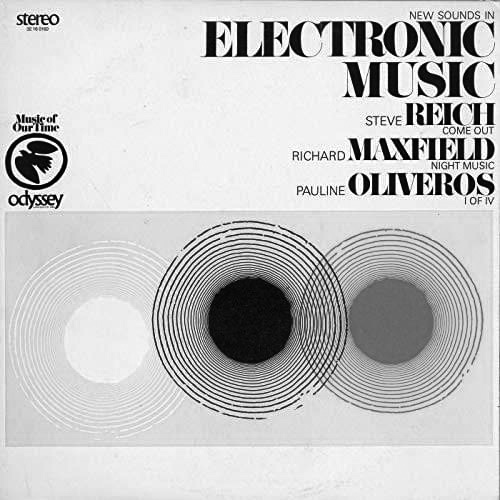

Steve Reich: ‘Come Out’ (1966)

For this piece, Reich used tape machines loaded with loops of a single phrase, “Come out to show them…”. The loops start together and gradually slip out of sync, creating a series of effects in the way the listener perceives the phrase. It phases, reverbs, echos, and eventually the voice is rendered unrecognisable and strange textures and rhythms emerge. It was released on the 1967 compilation ‘New Sounds In Electronic Music’ on the Odyssey label.

Pauline Oliveros: ‘I Of IV’ (1966)

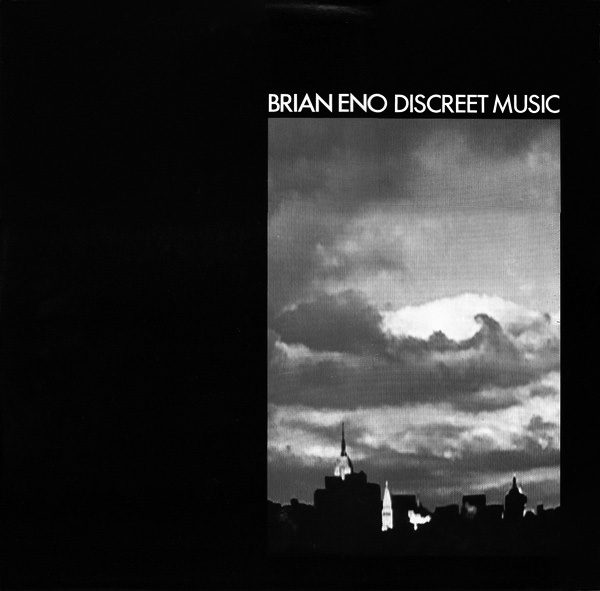

Also on the ‘New Sounds In Electronic Music’ album was this electronic/tape music piece by Pauline Oliveros. An abstract, electronically generated phrase was recorded, and then bounced into a second machine after an eight-second delay. It was then fed straight back into the first machine via various filters manipulated by Oliveros. It builds and swells and degenerates and refreshes like a pulsing, living beast over its 20-minute duration. Brian Eno used much the same process for ‘Discreet Music’ nearly 10 years later. Whereas Oliveros was interested in her piece being performed and mixed live, Eno’s initial phrase was more melodic, and his input to the process once it started was minimal.

BBC Radiophonic Workshop: ‘BBC Radiophonic Music’ (1968)

The Maida Vale studios of the Radiophonic Workshop were opened in 1958 with Daphne Oram and Desmond Briscoe in charge. The genius of its hard-worked composers reached its zenith with Delia Derbyshire’s realisation of the theme music for ‘Doctor Who’. Painstakingly put together with tape edits of concrète sounds, the theme used mathematical precision and calculations to create a piece of futuristic music that thundered along with the kind of beat accuracy that wouldn’t be achieved with electronic music until the invention of the sequencer. ‘Doctor Who’ isn’t on the 1968 library music release ‘BBC Radiophonic Music’, but this album is a tour de force of functional musique concrète and avant-garde electronic music, much of which was piped directly into British homes to massive audiences through radio and television themes and idents.

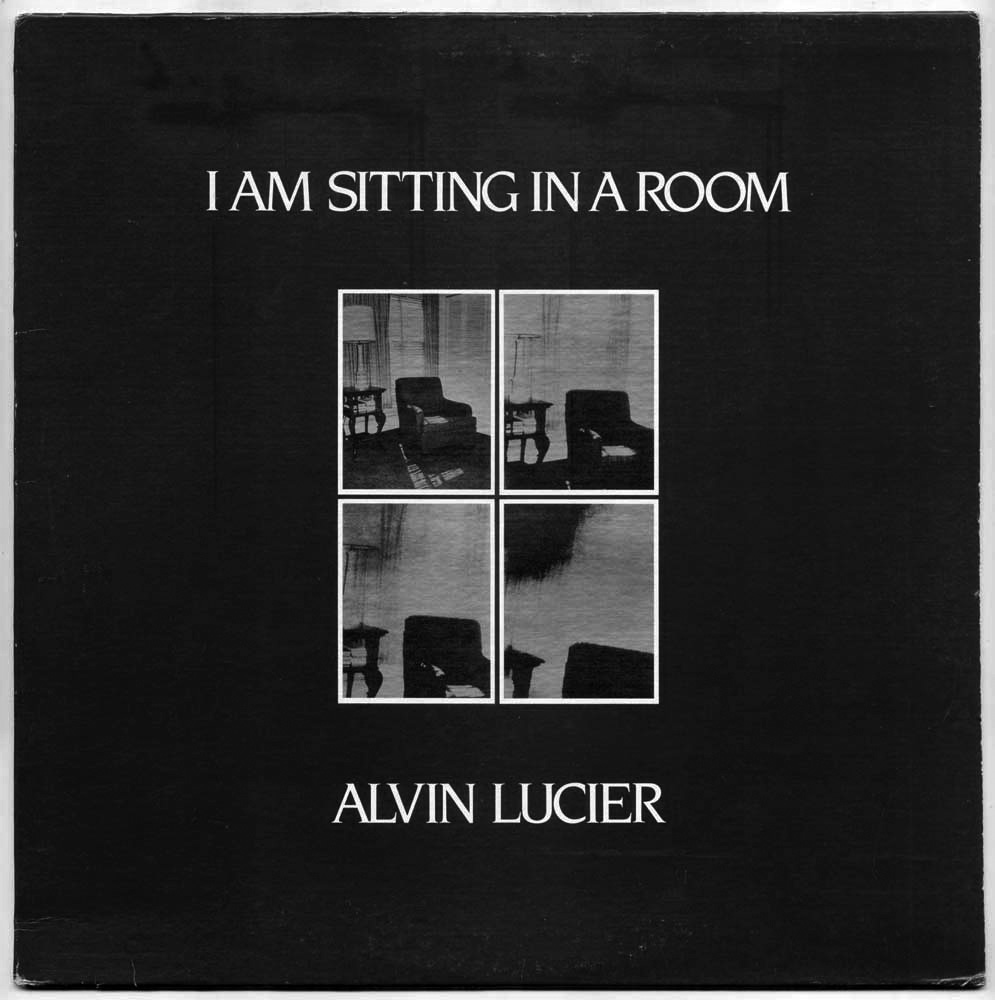

Alvin Lucier: ‘I Am Sitting In A Room’ (1969)

Lucier is an American composer who used tape to create this, his best-known work. He made a recording of himself describing the process he was about to embark on. “I am sitting in room,” he begins, “I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I’m going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonate frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed.”

He recorded this speech once, played it back in the room through speakers, and recorded the result, then played this second recording back through the speakers and recorded that. It took him all night, and by the end his voice is a continuous howl of resonant frequencies, which is really quite musical.

Brian Eno: ‘Discreet Music’ (1975)

Eno, along with the Radiophonic Workshop, was an important populariser of the methods and ideas around tape music. ‘Discreet Music’ was the result of a process which Eno came up with of a simple synthesiser line being played into a tape recorder, then re-recorded and played again in a series of gradually degenerating copies, with minor tweaks being applied to the synth line as it feeds through the endless looping of the tape machines. He had used a similar process for his 1973 collaboration with Robert Fripp, ‘(No Pussyfooting)’, where the live looping technique applied to guitar became known as Frippertronics.

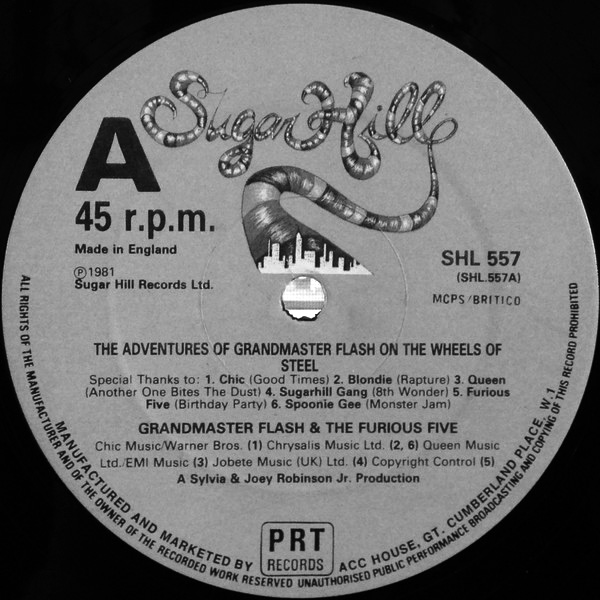

Grandmaster Flash: ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ (1981)

The 1970s saw the decline of tape splicing as an art form as the synthesiser became the go-to tool for people interested in creating new sound objects. The humble record deck was also undergoing a dramatic rebirth. In late 1920s, Paul Hindemith was perhaps the first turntablist with his “trick recordings” and John Cage had made pieces with turntables in the 1930s, before turning his attention to tape. In the Bronx, DJ Kool Herc discovered that with two turntables and a mixer, he could extend a break for as long as he liked. Records that gave Herc the breaks he was looking for included obvious candidates like James Brown, but they could come from anywhere, including ‘The Mexican’ by second-tier British rock outfit Babe Ruth and percussion heavy tracks from easy listening projects like The Incredible Bongo Band.

Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa both adopted Herc’s style, lifting snatches of beats and sounds from third-party vinyl to throw into the mix. And before you knew it, hip hop was born. The international breakthrough came in 1981 with Grandmaster Flash’s live, three-turntable masterclass ‘The Adventures Of Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels Of Steel’ that saw him mixing and scratching the likes of Chic, Queen and Blondie into one almighty track. Bambaataa wasn’t far behind when in 1982 he unleashed ‘Planet Rock’, which spliced Kraftwerk’s ‘Numbers’ and ‘Trans-Europe Express’ into a raw Roland 808 drum beat and the world of music changed forever.

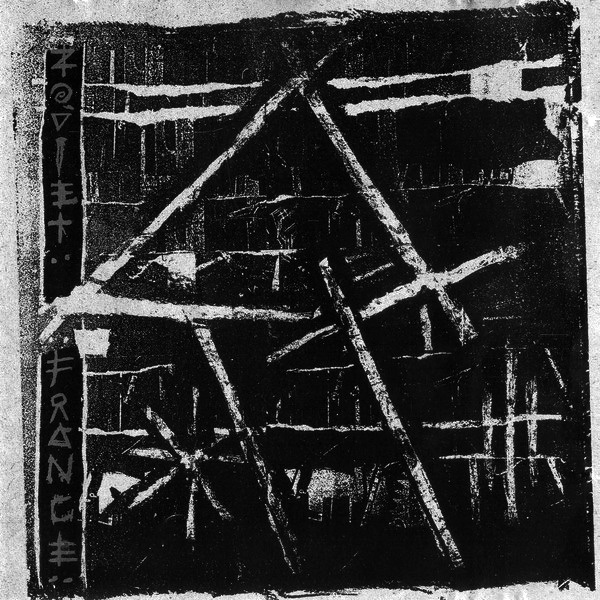

Zoviet France: ‘Mohnomishe’ (1983)

Still flying the flag for tape music as the musical world shifted its attention to MIDI and digital sampling, Newcastle’s Zoviet France mixed all manner of styles to come up with this, their hypnotically strange second album. It came sandwiched between two pieces of Masonite, a cheap type of particle board, which was screen printed by hand, making each copy a unique artefact. There are a couple of locked grooves on the album, and they also introduce acoustic instruments and other interventions. Their work bridges tape collage, sound art, ambient and noise.

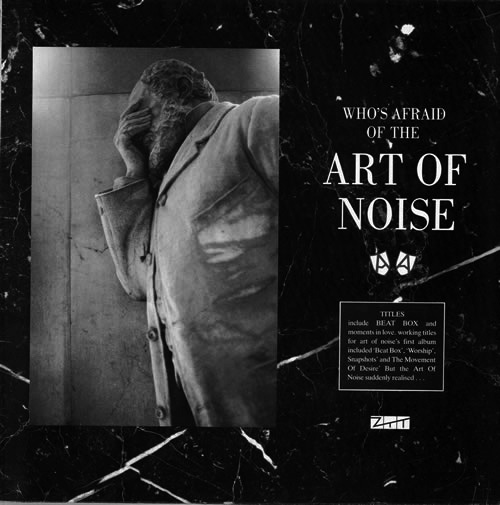

Art Of Noise: ‘Who’s Afraid Of The Art of Noise’ (1984)

With Trevor Horn at the controls, the Art Of Noise’s sample-fest showcased the Fairlight’s capabilities and laid down something of a template for creating digitally generated and controlled sound events using a computer-based sequencing environment. The sound of the mid-1980s pop would be dominated by the Fairlight’s set of factory samples and digital precision.

Christian Marclay: ‘Record Without A Cover’ (1985)

More recently lauded for his 2010 video art installation ‘The Clock’, a 24-hour montage of segments from films featuring clocks, which he put together so that the whole thing actually is a clock (he found footage of clocks and watches for every minute of a 24-hour period), Christian Marclay’s art practice is rooted in turntablism. ‘Record Without A Cover’ was indeed sold without a cover, the idea being that the accumulated dirt and scratches would enhance each unprotected disc. The sound of static, scratches and pops lifted from several records make up the first 10 minutes of the piece, and the rest is composed from cut-ups of various disparate musical sources, including classical recordings, a Hawaiian guitar record and a Duke Ellington album. He summed up his approach to records in an interview with The Guardian in 2005: “You can get so many sounds out of one record. Every record can be used in some way. If the music in a groove fits with what you’re playing, then play it; if not, then you can play it backwards. If that doesn’t work, you try it at a different speed. If it really doesn’t work you just break it.”

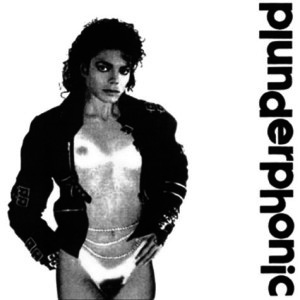

John Oswald: ‘Plunderphonics’ (1988)

In 1985, the rate at which turntablists and samplists were snatching sounds from the history

of recorded music and repurposing it for their own ends had reached such a pitch that it needed a new name. It wasn’t musique concrète. The sound objects here were all taken from existing recordings, from the work of other composers. It was stolen, nicked, plundered. And so the Canadian composer John Oswald coined the term “plunderphonics” in his essay ‘Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative’. What Oswald was trying establish was a school distinct from hip hop and turntablism, more a kind of satirical art movement operating at the outer reaches of copyright law, where outfits like The Residents created new work by cutting up Beatles recordings. Oswald’s 1988 12-inch EP, ‘Plunderphonics’, ripped Stravinsky’s ‘The Rite Of Spring’, Dolly Parton’s ‘Great Pretender’, Count Basie’s ‘Corner Pocket’ and Elvis Presley’s ‘Don’t’.

The Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu: ‘1987 What The Fuck’s Going On?’ (1987)

The JAMMS, who would become the KLF and dominate the pop charts of the early 1990s, first appeared with their own sample-heavy plunderphonic album that put ABBA into its sonic blender to the extent that the Swedish pop sensations issued a demand via MCPS (Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society) that the album should be withdrawn from sale and all remaining copies be destroyed. Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty packed up a Volvo and took a ferry to Sweden where they claimed they burned the remaining copies in a field. Any left over copies, they said, were thrown overboard on the ferry back home. The album kicked off with the sound of people having sex arranged into a rudimentary hip hop beat into which they slapped a slew of Monkees samples. It was every bit as bonkers, but perhaps not quite as artistically pure, as Oswald’s ‘Plunderphonics’.

Coldcut: ‘Say Kids What Time Is It?’ (1987)

Jonathan More and Matt Black’s first record was a watershed moment in underground music. It’s widely credited as the first pop record made entirely with samples. By assembling a new piece of music from small segments of existing recorded sound, Coldcut took the ideas of musique concrète, as mutated through turntablism and sampling, into the pop charts. The pair started their own record company, Ninja Tune, in 1990. Very quickly, Ninja became the de facto British home of a diverse roster of sampling/turntablist talent, signing and promoting a slew of artists whose musical tools were the turntable, a stack of vinyl, and the Akai sampler. Artists who found a home at Ninja include DJ Vadim, Funki Porcini, The Herbaliser, Kid Koala, Mr Scruff, and Strictly Kev, who heads up the long-lived Ninja project DJ Food. Coldcut also took the cut-up aesthetic into the visual world, developing software and techniques that allowed VJs to slice and dice video content in much the same way DJs did with audio.

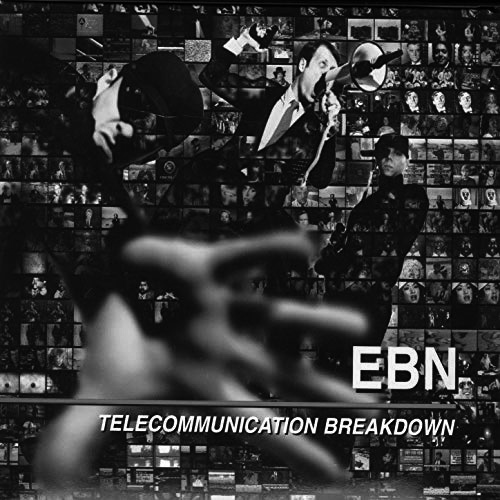

Emergency Broadcast Network: ‘Telecommunication Breakdown’ (1995)

Bay Area agit-prop art project EBN first gained prominence when their Gulf War remix video collage ‘We Will Rock You’, made up from clips of George W Bush taken from various speeches, was used by U2 on their Zoo TV tour in 1991. The album was one of the first “enhanced disc” CDs, and came with a floppy disc containing software. The music, produced by fellow samplist and sound explorer Jack Dangers, was made from audio taken from the video footage, which was also edited to create videos for each track. EBN’s Greg Deocampo later founded the Company of Science & Art who developed the ‘After Effects’ software, which they then sold to Adobe.

DJ Spooky : ‘Songs Of A Dead Dreamer’ (1996)

“Give me two turntables and I’ll make you a universe,” declared DJ Spooky (real name Paul Miller) in the sleeve notes for ‘Songs Of A Dead Dreamer’, his debut album. The record predated DJ Shadow’s ‘Entroducing’ by five months and, although a less well known work, is very much its equal in imagination, scope and originality. The fact that Spooky, who has since collaborated with everyone from Laurie Anderson to Ryuichi Sakamoto to Slayer drummer Dave Lombardo, also sometimes calls himself That Subliminal Kid is a sign of where he was coming from. And going to. He took the nickname from William Burroughs’ 1964 cut-up novel ‘Nova Express’. “I wanted to create music that would reflect the extreme density of the urban landscape and the way its geometric regularity contours and configures perception,” he continued in his album notes. “To me, assembly is the invisible language of our time and DJing is the forefront art form of the late 20th Century.”

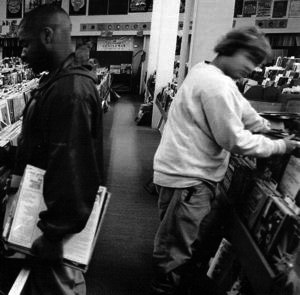

DJ Shadow: ‘Entroducing…..’ (1996)

The cover of DJ Shadow’s album ‘Entroducing…..’ is a photo of the cut-up DJ’s favourite activity: crate digging in a record shop. Shadow’s hour-long album of downbeat and moody instrumental hip hop was collaged from a wide range of sources and pulled together with an Akai MPC60, the pad-based sampler favoured by hip hop producers. Cracking the UK Top 20, it is one of the key release of the 1990s, and remains one of the most popular records to showcase the skills and techniques of the turntable collagist. Radiohead cited it as a major influence on their ‘OK Computer’ album, and invited DJ Shadow to support them on a tour, thus introducing legions of rock fans to the delights of minutely programmed audio collage.

The Avalanches: ‘Since I Left You’ (2001)

Melbourne group The Avalanches took musique concrète’s repurposing of pre-existing sounds to its limit in 2001. Their debut album, ‘Since I Left You’, reportedly employed over 3,500 samples, meticulously spliced together into a sampladelic morass that somehow had pop appeal and hooks. Drawing from familiar commercial records by Madonna, Rose Royce, Jefferson Starship and Kid Creole, as well as film dialogue, jazz and exotica, the album’s extreme plunderphonics recast neglected charity shop vinyl relics as sparkling new discoveries, and found value in pop that others had discarded. ‘Since I Left You’ reached the Top 10 of the UK album chart upon its release, and chimed with the European mash-up trend pioneered by 2ManyDJs, Freelance Hellraiser and Richard X, and by hip hop DJs such as DJ Yoda and the Scratch Perverts.

Mash-ups combined seemingly incompatible records in surprisingly effective hybrids. In 2001, Richard X made the remarkable ‘I Wanna Dance With Numbers’ as Girls On Top – an emotional mix of Kraftwerk and Whitney Houston that actually worked. They were popularised by ‘As Heard On Radio Soulwax Pt 2’, a 2003 mix compilation by 2ManyDJs, memorably meshing 10cc and Destiny’s Child and Dolly Parton with Röyksopp. It sold half a million copies worldwide. In the spirit of musique concrète, dusty sound artefacts were recycled and took on an entirely new form.

Matthew Herbert: ‘Plat Du Jour’ (2005)

While Matthew Herbert’s 1998 debut album, ‘Around The House’, gently tinkered with dancefloor beats and sounds sampled in the Herbert kitchen, he was clearly thinking along concrète lines. In 2000 he published a manifesto, ‘Personal Contract For The Composition Of Music’, which would act as a template for his future work. It included the banning of drum machines, synths, presets and the sampling of other people’s music. The self-explanatory ‘Bodily Functions’ on Studio !K7 was his first offering to obey the manifesto. In 2005, he released ‘Plat Du Jour’, a record that drew its sound sources from food, drink or its packaging, which veered from 3,255 people crunching apples to a tank driving over a recreation of a meal Nigella Lawson prepared for George Bush and Tony Blair. While always remaining musical, Herbert manages to subvert with almost everything he touches. His 2011 release, ‘The End Of Silence’, used a five-second audio clip of a bomb exploding to create an entire record, while in 2016, ‘A Nude (The Perfect Body)’ recorded the noises a naked human body made for an entire 24 hours. Much of his output is pitched between conceptual art and political statement and has seen him rail against big corporations, global finance, climate change and food production. Indeed, his 2011 album, ‘One Pig’, charts the life cycle of a pig from birth (’August 2009’) to the dinner table (’May 2011’). Criticised by animal rights organisations for exploiting the animal’s death for “entertainment”, he responded in by saying he hoped it would encourage people to “listen to the world a little more carefully”.

Howlround: ‘The Ghosts Of Bush’ (2012)

Robin Warren and Chris Weaver’s debut album as Howlround was a spooky environmental study made from tape recordings of Bush House, the BBC recording facility where Warren worked. Having grown up inspired by jungle and hardcore, before discovering their antecedent, musique concrète, Warren captured found sounds around the building, its natural reverb and echoes, then manipulated the spools of tape to convey the uncanny nature of the large stone interior. Inspired by artists like avant-garde sound sculptor William Basinski, Howlround’s take on musique concrète also nodded to the hauntology of artists like Pye Corner Audio, Boards Of Canada or Belbury Poly, whose strange, spectral evocations of the recent past via crackly old samples and nods to obscure 70s TV themes had more than a hint of the unsettling. The way ‘The Ghosts Of Bush’ preserved the atmosphere of the space was remarkable, a trick that Warren performed again with the follow up ‘Secret Songs Of Savamala’, this time finding a muse in the flooded basement of an abandoned Serbian customs building. The former is among the best recent examples of musique concrète and, in its title, it nods to another milestone of the genre: Byrne & Eno’s ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’.

Amon Tobin: ‘Fear In A Handful Of Dust’ (2019)

After an album with NINEBARecords under the name Cujo, Amon Tobin joined Ninja Tune and released ‘Bricolage’ under his own name in 1997. It did what it said in the tin, taking a term from the visual art world for work that is created from various already available bits and pieces, and applying it to music. ‘Bricolage’ is the result of taking various musical sources, cutting them up and reordering them. It didn’t adhere to any particular dance culture parameters, though it occupied a Venn diagram slice where trip hop, hip hop, jazz and experimental electronic music overlap. In its intricate reconstructing of beats from old jazz records on tracks like the frenetic ‘Creatures’, it was taken as a leap forward for drum ‘n’ bass, particularly in America. The fact that the cover art featured an abstract image of a piece of sculpture (Alexander Liberman’s ‘Olympic Iliad’) should have communicated where Tobin’s head was at – the intersection of architecture and sound, much like the collaboration between Le Courbusier and Edgard Varèse back in 1958. Over the following 20 years, Tobin was able to pursue his ideas with a series of albums with titles which continued to flag up what it was he was interested in, among them ‘Permutation’ (1998), ‘Supermodified’ (2000), ‘Foley Room’ (2007) and ‘ISAM’ (Invented Sounds Applied To Music) (2011). The 2019 album, ‘Fear In A Handful Of Dust’, maintains all the sonic obsession of a committed sonic explorer and takes it into a more emotionally charged arena, sublimating the “squishy” human experience into a musical exploration of beauty and warmth.