“I always kinda knew that Debbie was this fantastic thing, on many levels. so it seemed justified that she should get a lot of attention” – Chris Stein

Blondie ‘Parallel Lines’

“When Blondiemania blew up,” says Chris Stein, “it was insane. And tiring. Then again, I’m always optimistic, so it seemed like it was right.”

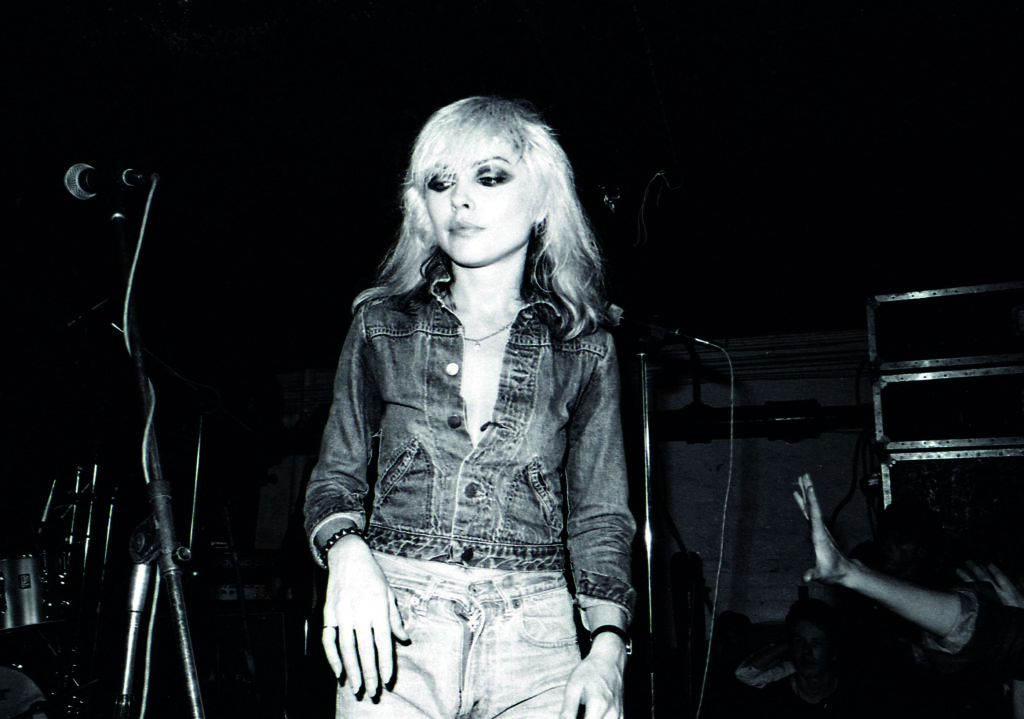

As the New York art-pop bands landed almost accidentally upon world domination, it was Blondie who were, in every way, the public face.

“I always kinda knew that Debbie was this fantastic thing, on many levels,” continues Stein. “So it seemed justified that she should get a lot of attention. It seemed not unreasonable. We’d had our first hit in Australia, but it didn’t translate to ‘mania’. Then there was a tour in the UK and suddenly people were storming our bus. At one record store signing in Kensington High Street, the streets were blocked off, traffic stopped, there were thousands of people… That was a terrific day.”

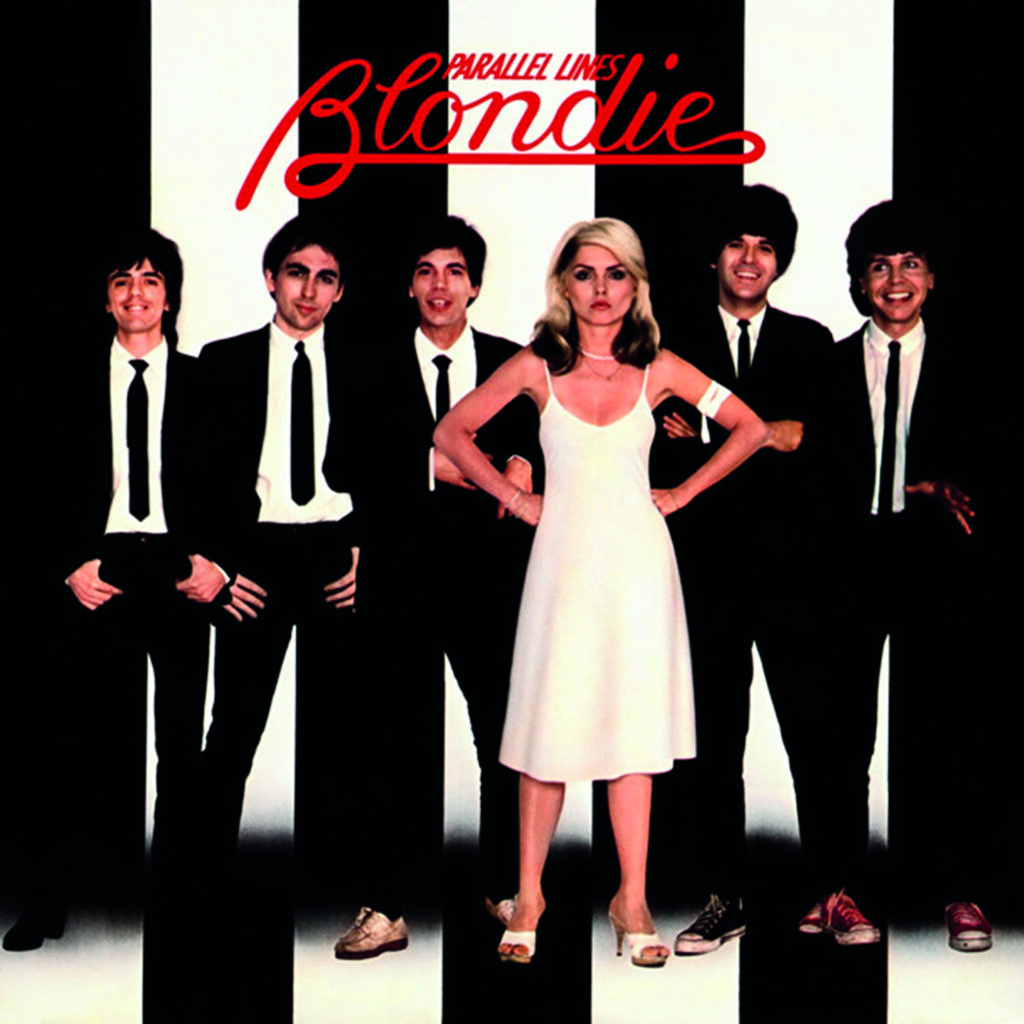

The phenomenon which had tipped the world over the edge was ‘Parallel Lines’, the hit-packed crossover album released in September 1978. It elevated Blondie from cult, downtown art-rockers to bona fide global pop sensations. Lester Bangs called their new music, “New wave for that great mythic Ozzie and Harriet audience out there in the heartland”. Mike Chapman, the record’s producer, who had honed his skills firing out hits for glitter rock greats like The Sweet, Mud and Suzi Quatro, thought it was just “modern rock ’n’ roll”.

Yet surprisingly, it was an enduring dancefloor landmark of faux-electronica which sent Blondie stellar. ‘Heart Of Glass’, a wonky, uneven, yet somehow irresistible slice of Kraftwerk meets ‘Saturday Night Fever’, pretty much an afterthought during the album’s recording process, had hummed and throbbed its way to a transatlantic Number One by March 1979, leaving many among Blondie’s punk following peeved but the rest of the planet euphoric. Guitarist Jimmy Destri admitted its success left the band with “a certain amount of guilt”. It also left them adored and famous. Against all expectations, and contrary to the opinions of the music critics of the era, ‘Heart Of Glass’ now stands as one of the most influential pop records ever made.

In many ways, ‘Heart Of Glass’ overshadowed the bulk of ‘Parallel Lines’. It shouldn’t have. Mike Chapman – and, not short of ego, he’s always happy to confirm this himself – had whipped the talented but quirky and naturally alternative Blondie into peak shape. Chris Stein doesn’t deny it.

“Oh, absolutely, I wouldn’t dispute that at all. We did the first two albums just going in, playing the songs a few times, trying to improve them a little. But when we got in with Mike for ‘Parallel Lines’, it was like, ‘Playtime’s over!’. Everything had to be super-precise. I mean, ‘Heart Of Glass’ sounds like a modern computer song now, a ‘MIDI’ song, right? But it was all manual. Nowadays, you don’t have to play the bass drum for three hours, you just play two bars and loop it. Most pop music is done through cut and paste. But this was crazy. Every time you hear any of those notes on that track, they’re played at that time. Looping or sequencing didn’t exist then.”

As a backdrop to the recording of ‘Parallel Lines’, the summer of 1978 saw the worlds of Disco Sucks and Disco Rules collide and coalesce, as the children of CGGB’s grew up and saw a bigger picture.

“We were such an urban band,” says Debbie Harry, recalling late nights at Studio 54 soaking up disco heat. “Chris and I were huge fans of Chic and Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder. That techno kind of thing entered our picture, with Jimmy playing synthesisers. It seemed a natural evolution for us, to graduate towards new instruments. Then we were in the studio and we’d had this song ‘Heart Of Glass’ under various names, such as ‘The Disco Song’, for years. It just sat there and we’d never used it properly.

“We’d tried translating it so many ways, but it never really worked. Anyway, Chris and Jimmy used to go around 47th Street, where all the music stores were. One day they came back with this little rhythm box, which went ‘tikka takka tikka takka’, and the rest is history! That was the beginnings of the track as you know it. It just blew up. We all went, ‘Yeah! That works!’. It sorta drove Clem crazy, though, and he may have a different recollection…”

Clem Burke, Blondie’s drummer, does. Although he was a fan of the Bee Gees’ contemporaneous rhythmic classics, the recording of ‘Heart Of Glass’ was no picnic for him, nagged by Chapman into days of relentless repetition, pretty much the polar opposite of all his instincts. Unlike the public at large, it took him years to learn to love the song.

The public had learned to love Blondie after their eponymous 1976 debut album had taken them out of New York, while ‘Plastic Letters’ had given them UK hits in the shape of ‘Denis’ and ‘(I’m Always Touched By Your) Presence, Dear’.

“Pop was established there,” says Debbie, musing on their acceptance in London, “and we were – in the main – a pop band. Even though we thought we were underground and subterranean. Our subject matter was sometimes dark, but we had a pop sensibility. And pop hadn’t quite re-emerged in the States at that point…”

It was about to, though. ‘Parallel Lines’ became ubiquitous, selling over 20 million copies worldwide. It was the bestselling album in Britain in 1979.

Yet as a third album, it had begun its pre-life as possibly, in the record company’s eyes, a make-or-break shot. Everyone had twigged that Debbie was fabulously photogenic, an actual star, but as a commercial conduit was that being maximised? Chrysalis co-founder Terry Ellis declared, “I want to make them into a worldwide multi-platinum success”. So Aussie Chapman replaced New Yorker Richard Gottehrer, who had produced ‘Blondie’ and ‘Plastic Letters’, and the band were told they were capable of more. “I raised the bar”, Chapman said, “to a point they didn’t even know existed”.

The months leading up to the ‘Parallel Lines’ sessions had been getting increasingly weird for Blondie. In a way it had started in 1977, when the band supported Iggy Pop on his North American tour for ‘The Idiot’, with David Bowie playing keyboards for Iggy. Chris Stein explains what a class act the duo of deities were to them.

“They were awesomely professional, sweet and gracious,” he says. “A tough act to follow. Later tours with other bands who were more competitive were a comparative disappointment. Bowie gave Debbie pointers about stagecraft. It was a great way to start our touring career.”

The rest of 1977 was manically busy for the band. “I realised I never saw ‘Saturday Night Live’ that year because I was out every Saturday,” says Chris. The gigs included their first visit to the UK, playing with fellow CBGB’s graduates Television, which was crucial to the buzz around them. And as 1977 morphed into 1978, Fab 5 Freddy took Debbie and Chris to a very early hip hop gig in the Bronx. This eventually inspired ‘Rapture’, but it had already seeped into their musical subconscious.

Blondie spent six weeks at Record Plant, New York City, in June and July 1978. But ‘Parallel Lines’ wasn’t all sunshine and roses to record, with some fractious moments occurring.

“There was a certain amount of competition within the band,” admits Debbie, “never mind outside it. Who was writing what songs… I’m not gonna point fingers at anybody, because at the same time, strangely, we all really stood up for each other too. I guess we were sorta like brothers and sisters: healthy rivalries, in a way. I wasn’t going to be anybody’s victim and I wanted to do what I did on my own terms. I was a stubborn young woman, but as vulnerable a human being as anyone else.”

Mucho mistrust, indeed. Debbie hadn’t been keen on Mike Chapman’s appointment either. Chapman has said she thought “they were New York and he was LA”. He’s suggested that Chris was stoned too often in the studio and that the band, apart from Debbie and Chris, were arguing a lot among themselves, with the normally mild-mannered Nigel Harrison even throwing a synth at him. Chapman has claimed that he “went in there like Adolf Hitler” with his work-hard ethic, and that he drove Debbie, who was scribbling down lyrics seconds before a take, to tears.

Yet when, astonishingly, Chrysalis weren’t instantly convinced by the album’s class, even talking about a complete makeover, it was Chapman who persuaded them to unleash it upon the world. But even then there were wobbles – the title came from an unused lyric and the iconic record cover was unloved by the boys, including Chris, who thought it reduced him to a background figure in his own band.

Of course, the net result is a joy, a fairground ride of harmonised adrenaline. ‘Parallel Lines’ had it all, the perfect package – the songs, the production, the image (that cover), and the attitude. The deceptive depth and poetry of ‘Picture This’ was the first single in the UK, although in the States it was ‘I’m Gonna Love You Too’.

Then came the venomous ‘Hanging On The Telephone’, followed by ‘Heart Of Glass’. ‘Sunday Girl’ (another UK Number One) and ‘One Way Or Another’ (US only) kept the hits coming.

“The only one I knew was great was ‘Hanging On The Telephone’,” says Chris, “because we were in Japan playing it on a cassette machine and the Japanese cab driver started tapping his fingers on the steering wheel. I thought, ‘Wow, if it spans these gaps of culture, there must be something to it!’.”

‘Parallel Lines’ was the ‘Thriller’ of its day; a much-needed no-filler blast of pop brio, when the previous year, as Chris Stein recalls, “I felt pursued around the world by ‘Hotel California’. It was inescapable, emerging from radios wherever I was. It sort of drove me crazy.”

‘Parallel Lines’ proved you could check out of long-hair rock and leave the punk ghetto with your principles intact. ‘Fade Away And Radiate’ even offered a glimpse of “blue blue neon glow” Euro-style synthpop, Robert Fripp free-forming over the outro. And yes, there was its secret weapon humdinger, ‘Heart Of Glass’, which staked its claim as the first white disco smash, albeit after the likes of Bowie’s ‘Young Americans’ and Roxy’s ‘Love Is The Drug’, and contributed as much to the rise of the machines in the popular consciousness as ‘I Feel Love’ or ‘Trans-Europe Express’.

“It just worked out nicely for us, for all the bands,” says Debbie. “The fact that everybody grew up and got momentum and colour and interest: the Ramones, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Television. People were now going, ‘Oh, let’s record these guys’. And that’s what all of us had wanted. When you start up a rock band, you envision yourself being whoever is the biggest thing in the world at the time, you know? Like, why else would you do it? We always had a lot of passion for what we did.”

And it was a gas.

‘Parallel Lines’ was released by Chrysalis in September 1978