Epic and mesmeric, sensual and influential, ‘Phaedra’ is Tangerine Dream’s definitive masterpiece. It was recorded under trying circumstances, but the album’s sequenced, otherworldly sounds – built on Mellotron and Moog synths – arguably resonate even more today than they did in 1974. To mark its 50th anniversary this month, we tell the story of an enduring cornerstone of progressive electronic music

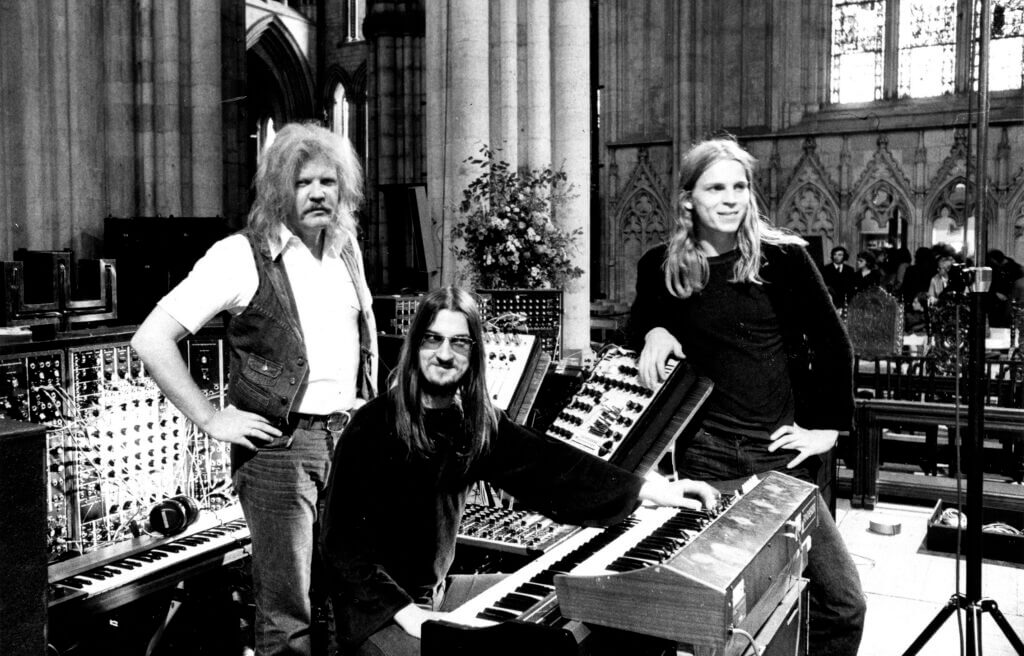

In November 1973, the members of Tangerine Dream arrived in London on a half-empty BAE flight from Berlin. Their equipment was simultaneously transported by a somewhat ramshackle Daimler truck to Calais by road. The group, then comprising Edgar Froese, Peter Baumann and Christopher Franke – a new form of power trio – had been successfully enticed by Richard Branson to join his fledgling Virgin label.

The three were only too grateful. They were at loggerheads with their previous imprint Ohr, founded by Rolf-Ulrich Kaiser – a mercurial fellow who would ultimately fade away in a haze of his own making because of his attempts to meld all of the bands on Ohr’s roster into a shifting collective under the banner of Cosmic Couriers. As well as an understandable desire for autonomy, the straight-edged Froese took a very dim view indeed of the acid-fried dysfunctionality into which the label was descending.

“The founder of the label was a little bit… strange in the brain,” says Baumann when we speak. “He went off the deep end. We didn’t really feel that the Cosmic Couriers thing was our cup of tea.”

Branson, musical director of Virgin, had ventured to West Germany in search of new talent to supplement British acts on his label, which included Gong and a certain Mike Oldfield. There, he would sign the Hamburg-based Faust. German Polydor had previously signed Faust on the promise that they would be the “new Beatles”, only for them to turn out to be the very avant-garde antithesis. Consequently, they were dropped and, in 1973, ejected from their Wümme studio compound, they were living on dog food.

Branson had also made an offer to Froese and co to come and record a new album in England. This rescued Froese, who died in 2015 aged 70, from what he described in his autobiography, ‘Tangerine Dream – Force Majeure’, as an “existential crisis”. He paraphrases the menaces he felt TD were being threatened with by Ohr when they took legal action, and the word put about by them to their German music business and press contacts:

“The Berlin group Tangerine Dream will achieve in court precisely what the band means to the German music scene, namely NOTHING.”

Here they all were, however, in the UK in 1973, in what represented a rather unnerving culture shock. Peter Baumann remembers the journey he and the group took to The Manor in Oxford, a Tudor house converted into a studio sitting in several hectares of land.

“I remember very well when we arrived – this was in the 1970s when they had the oil crisis. We saw the long lines of cars at the petrol stations.”

Keeping the trio company in the car Branson had laid on for them was a rather menacing-looking dog, an Irish wolfhound by the name of Bootleg who, they were assured, only turned violent when he deemed himself to have been provoked. They arrived at the studio, a haven amid the economic gloom of early 70s Britain, under slate-grey skies and driving November rain.

“When we reached The Manor, there was nobody there,” recalls Baumann. “We looked around and eventually found the whole gang in a room – all sitting watching TV, everyone completely stoned. And they were wonderful people, but they said, ‘We just had some pot brownies for dinner’.”

All of this was congenial to the youthful Baumann, much less so to Froese. If Ohr were no longer Tangerine Dream’s cup of tea, then The Manor studio was certainly not their cup of coffee – Froese described the coffee in the canteen as tasting like “diluted vegetable stock”. The food was abysmal too.

“It was cooked with love but in an unfortunate British way, free from any exotic spices and free from any leanings towards an international cuisine,” wrote Froese. “Porridge with soft boiled cauliflower was a particular delight.”

Froese chose to view it all as a “karma-style survivable experience”. What other choice did he have? He was even less impressed by the state of the studio itself, which he described as “a technical rubbish dump”. Faced with Froese’s misgivings, the studio engineer assured him that Mike Oldfield had just recorded an album there that had gone very well. “Good for Mike Oldfield,” thought Froese, “whoever the hell he is…”

However, this was of little consolation when the initial recordings for the album that would become ‘Phaedra’ were marred by a power failure, plunging the studio into complete darkness, along with an earache-inducing crackle on a malfunctioning mixing console and a roof leak that saw heavy rain drip into all parts of the studio. The group were on an extremely tight, 14-day time constraint – Gong were booked to come and record immediately after them – but the first two days of their tenure were spent waiting for equipment to be repaired. Little wonder they nicknamed the studio the “crackle ballroom”.

The nadir came when Bootleg the Irish wolfhound looked in at the studio, then trotted up to the Mellotron, cocked his leg and pissed into it copiously. Incense sticks had to be fetched to negate the stench of wolfhound urine.

Baumann in particular was sanguine about these developments as, in keeping with the spirit of The Manor, he began every day by “partaking”. “A joint in the morning and the day is your friend” was his maxim.

“Everyone there bore a relaxed expression,” noted Froese of studio staff and fellow group members alike, feeling that he alone was bearing the burden and stress of recordings which had yet to begin.

Some respite came when a couple of tech whizz-kids known as the Bradley brothers helped Froese change the tapes on his Mellotron. Work could commence, with the three band members working alone and in tandem, attempting to generate ideas completely from scratch. But for whatever reason, they came up short – finding their way around the Moog synth or hitherto practically unknown instruments like the sequencer.

The terrible English weather certainly didn’t help either, putting paid to the long walks the band liked to take to clear their heads prior to recording. Instead, they had to make do with congregating on a dilapidated tennis court on the Manor grounds. And then, just as things couldn’t possibly get any gloomier, and with just days left of their allocated studio time, Christopher Franke’s Moog malfunctioned, susceptible as it was to even small fluctuations in the electricity supply.

Froese and Baumann left Franke alone so that he could re-tune the instrument. As they sat in the kitchen, ruminating over British hot chocolate – the only beverage acceptable to them – on what a shambles these sessions were, an eerie and compelling sequencer loop beamed through from the studio, like a chink of light. This, Froese instantly realised, was a sequence that absolutely had to be recorded. By sheer force of chance, a breakthrough at last…

“I ran into the studio and grabbed Franke by both arms so that he couldn’t alter any more settings,” stated Froese in his autobiography.

Franke was indignant, insisting he could get that sound any time, and the pair practically wrestled in the studio to the amusement of the ever-genial Baumann. But Froese prevailed, the tapes began to roll and the cornerstone of the title track to ‘Phaedra’ was in place.

“They went into the studio every single day for three weeks and made hours and hours of meandering, directionless and quite honestly not very successful music,” says Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, who remastered ‘Phaedra’ in 2019 and had access to the session tapes in their entirety.

“Sometime in the third week, they go in and you can sense it – they’re all at their wits’ end. And something happens. Genius descends. And they go on to create this masterpiece. If you hear, as I have, all the failed attempts, the run-ups… it makes it even more magical.”

Edgar Froese started his musical life in the 1960s, in a style typical of many young West German artists, aping the mannerisms and tropes of Anglo-American groups from which they would later radically depart. Tangerine Dream were unabashedly influenced in their foundation by English psychedelia, as evidenced by Froese’s pre-TD combo The Ones, who disbanded in 1967 after just one single. In addition, Froese attended closely to early Pink Floyd, while The Beatles’ ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ was very much on his radar too.

But Froese experienced a mini-epiphany early on when a group of his were invited to play at Salvador Dalí’s villa in the town of Cadaqués, Spain. Proximity to the extravagant, surrealist genius in the midst of his opulence prompted Froese to pursue a more experimental direction, finding ways in which the radical, formalist movements of 20th century art might similarly open up new horizons for the relatively stinted, blinkered beast that was mid-60s beat music.

“Everything is possible in art,” the 22-year-old decided, as he embraced the potential of the “absurd”, previously considered unimaginable or beyond the pale in Anglo-American rock hegemony. Froese was on the point of taking a decisive, quantum leap.

He was already studying painting and sculpture in Berlin, and so dropped naturally into the cultural scene revolving around the Zodiak Free Arts Lab, located in Hallesches Ufer in West Berlin and co-founded by Conrad Schnitzler, Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Boris Schaak. The Lab only opened late at night after the regular theatre in which it was sited was closed, so that the raucous and anarchic musical performances it hosted would not drown out the theatrical ones.

The Arts Lab was wilfully chaotic – Schnitzler had painted the venue black, including the windows, and bands played simultaneously, competing with the clatter of pinball machines and radios. Drugs were taken. But the Arts Lab was an incubator, not just for avant-garde West German musicians but political groups such as the Umherschweifende Haschrebellen (Rambling Hash Rebels) or agit-pop combos like Ton Steine Scherben.

The late 1960s was a time of both musical and political insurrection, but this had a particular resonance with the young West German generation. Coming of age, the most politicised elements were angrily conscious of the sins of their fathers and grandfathers in the Third Reich, and the silence they exuded about their generation’s heinous crimes in the years of post-war “reconstruction”. They took solace in the music of forgetting – like Schlager, or the Coca-Cola-ised boons of the occupying Anglo-American culture – with young musicians having to earn their chops, playing everything from The Beatles to Motown for GI troops at weekend parties.

This sense of cultural humiliation may not always have been conscious but it cut deep. It was no coincidence that not just in Berlin, but in Cologne (Can), Düsseldorf (Kraftwerk, Neu!) and Hamburg (Faust), musical collectives were springing up, often resorting to electronics inspired by forefathers like Karlheinz Stockhausen to conceive new music, West German in origin, free of the shackles of Anglo-American rock domination. Despite being a guitarist, Froese always felt there was something inherently absurd about Germans attempting rock.

“We didn’t have the attitude for rock ’n’ roll, the blues and so on,” he told Mojo’s Andy Gill in 1997. “What can you do if you are in a position where you can run round in circles and still never catch up with what is already there? That period of time was when Clapton was big with Cream, and Hendrix was big – what did it mean for a German to take a guitar and start playing like that? It was ridiculous.”

Baumann concurs with this today.

“The thing is, it’s not in the German culture to have rock ’n’ roll bands. There are very few. OK, maybe now it is different. Back then, you had the Scorpions but otherwise very, very few. That showmanship you have in the UK and the US, you just didn’t have in Germany.”

The original Tangerine Dream line-up comprised Froese, Conrad Schnitzler and Klaus Schulze, the latter two very wilful characters who went their very individual ways, against the grain of the generally collective spirit of krautrock. They released their debut album, ‘Electronic Meditation’, their sole recording as an ensemble, in 1970.

“Electronic” was a slight misnomer as the trio did not at this stage possess electronic equipment – rather, they modified their instruments, used sound effects and tapes, and devices such as a slide calculator called the Addiator to create a chalk and pins outline of a future music, impressive in its vast range despite its lo-fi recording methods. The title of the opening track, ‘Genesis’, was an appropriate harbinger for Froese’s grandiose ambitions.

Schnitzler’s involvement in this album also spoke of Froese’s anti-rock stance, an outsider-ism which prefigured punk in its ethos, as described by Schnitzler in David Keenan’s interview with him for The Wire in 2006.

“I said to Edgar, ‘You know I cannot play?’. He said, ‘That’s good’. This was when Froese and Klaus Schulze were playing together. They played rock music, and I was there to break the rock music, to make it kaput. I did everything against it, putting as much noise in as possible.”

“We have maybe been the first electric punks in history in 1970,” Froese later commented to American music journalist Jim Sullivan.

The album was released on the Ohr label, with whom the group would develop an ultimately fractious relationship. The follow-up, ‘Alpha Centauri’, was released in 1971, with a line-up that now included Christopher Franke. Although its dark, billowing aesthetic was still dominated by acoustic instruments such as organ and flute, electronic instruments were coming to bear on the Tangerine Dream sound via a guest appearance by Roland Paulick on synthesiser and a VCS 3 courtesy of Franke.

Froese was now talking openly about “kosmische” music, but this was clearly not the cosmos in a friendly, astrological sense, forming alignments to boost humanity’s prospects of having unexpected career opportunities or pleasant surprises in store. This was a universe that was remote, indifferent to humanity, way above and beyond the fallen Earth – not dissimilar to Stockhausen’s post-war electronic visions.

“We listened quite a bit to Pink Floyd, but also to Ligeti and Stockhausen,” says Baumann.

‘Zeit’ followed in 1972, the first album to feature a young Baumann, who now downplays the cosmic significance of his early efforts with the group.

“We had no idea what we were doing. We were just a few dudes having fun making weird sounds. There was no real thought behind the direction. That’s what we loved to do and that’s why we did it.”

Nevertheless, whether intuitively or otherwise, Tangerine Dream were taking great shape. Florian Fricke of Popul Vuh contributed to the opening ‘Birth Of Liquid Plejades’ track, playing Moog synthesiser, an extremely rare and expensive instrument at that time, which he’d only been able to acquire because of his private means.

‘Zeit’ certainly stood out. The album’s terse title alluded to the notion that time as we understand it in our minds is illusory – in fact, time is a static concept. This went against the very idea of “progress” that underpinned most 70s rock. Instead, Tangerine Dream presented a sort of stasis, despite their rejection of repetition. It’s like scanning the night skies, in all their remote variegation, a celestial panorama of unrelated activities, ominous in their indifference to humanity. In its beatless, overarching unearthliness, ‘Zeit’ would prefigure a great deal, including even ‘(No Pussyfooting)’, Brian Eno’s 1973 collaboration with Robert Fripp.

‘Atem’ followed in 1973, the last of what was termed their “Pink” series of albums for Ohr. Dominated by its 20-minute title track, it would see Froese make up for the loss of Fricke’s Moog with the acquisition of a Mellotron. Crucially, the album caught the ear of Radio 1 DJ John Peel, who declared ‘Atem’ one of his albums of the year. His patronage would help clear the way for Tangerine Dream to be introduced to a British listenership.

Fast-forward to November 1974 and, with just a few days of recording time left, Tangerine Dream still had to find 22 minutes of acceptable music.

After completing the track ‘Phaedra’, next up was the piece that would become ‘Mysterious Semblance At The Strand Of Nightmares’, which perhaps sums up the sense that Tangerine Dream were pulling inspiration from thin air in the face of desperate circumstances. Credited to Froese alone, the track was triggered by using a box which Froese had purchased in Berlin and brought over to the UK, one that produced phaser and flanger effects absolutely commonplace on any computer in 2023, but which were quite unknown back then.

He had arranged to start the studio session two hours early – despite the proclamation that underpinned ‘Zeit’ regarding the static nature of time, Froese was concerned that the clock actually was ticking and it was a matter of urgency to get something recorded pronto. Worried as he was about the “mental state” of both Baumann and Franke at this stressful stage, he enlisted the help of his partner Monika to produce what he described as a “musical quickie”. He explained to Monika how to use the filter knob on the phaser while he played Mellotron.

When Baumann and Franke arrived at the studio and were presented with this first take, they were not best pleased. Feeling that this modus operandi breached the protocols of the way Tangerine Dream worked, Baumann rather coldly asked if they were still a three-piece, before embarking on a lengthy walk in the woods. Sarah, the Manor cook, informed Froese of Baumann’s sojourn and that, Captain Oates-like, he “may be some time”.

However, the group then reassembled to produce the track ‘Movements Of A Visionary’. And then, later that night, Baumann made another oblique disappearance, stating that he had to run some checks on his instruments. In fact, he had other ideas.

“I did my piece [‘Sequent C’] on the very last night,” recalls Baumann. “There was a mobile unit in the parking lot, and I was in there with a recorder, recording and mixing it all night long. We needed the material.”

Froese described Baumann’s complexion as he arrived at the breakfast table the next morning as “the same shade as the grey, chafed flannel of his trousers”. Baumann announced that he had produced a track of his own accord, one out of keeping musically with the rest of the album, given the circumstances of its making, but uniquely resonant, nevertheless. Froese suspected the very making of the solo track was a passive-aggressive response to his having recorded ‘Mysterious Semblance’ alone, but he let it go, content to admire Baumann’s hitherto unsuspected prowess on the recorder. The music was in the can.

Richard Branson and Virgin A&R man Simon Draper visited later that day.

“Simon Draper came over and listened to the record and smoked a joint,” says Baumann. “He didn’t say anything for a few minutes and then he said, ‘That’s just an amazing piece of music’.

And that was the first time we thought, ‘Wow, maybe we’ve got something here’.”

Although Branson was the dealmaker at Virgin, the man with an eye for a commercial opportunity, Draper was the far more knowledgeable of the two. Branson had put Draper at the helm of his musical operation, having first met him as a 20-year-old in 1971. Born in South Africa, Draper had been fanatical about music from a young age, even hosting his own radio station in Durban. He specialised in imports, working diligently with Virgin’s mail order business prior to the establishment of the label proper. And he would buy up copies of albums by artists like Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart to jump the gun, as in the early 1970s there was still a lag of a few months between their US and UK release.

At a time when rock critics still regarded the idea of German music as inherently comic, unable to resist gratuitous references to sauerkraut, “Achtung!” and headlines like “Ve Haff Vays Of Making You Listen” (and this was just the supposedly ultra-hip and progressive New Musical Express), Draper understood that something serious was going on in West Germany. He had ordered a job lot of albums from Tangerine Dream’s Ohr label and marked out Froese and the group as commercially viable.

“Because it was instrumental music, it had international appeal,” says Draper. “There was no language barrier. In contrast to the huge problems we had selling French music outside France, for example. Tangerine Dream were international, the lingua franca.”

Moreover, via his mail order dealings, Draper was clued up and very conscious of what kind of music was in demand. He’d seen the success of Tonto’s Expanding Head Band, the pioneering electronic project of British-American duo Malcolm Cecil and Bob Margouleff, who would help Stevie Wonder produce his superb series of early 70s ARP and Moog-based albums including ‘Talking Book’ and ‘Innervisions’.

In 1974, Edgar Froese spoke of having told a Melody Maker journalist that in 10 years’ time, everyone would be using synthesisers, and of the journalist terminating the interview, concluding that Froese had a screw loose. Draper understood that despite such synthphobia, there was a potentially huge audience for electronic music. The success of Tonto’s Expanding Head Band persuaded him that Tangerine Dream could enjoy great success too – indeed, for him, it was never in doubt.

“I knew that sort of thing would sell.”

But when Virgin set up their record label, they were outsiders.

“It wasn’t possible for us to sign mainstream acts,” admits Draper. “Even people like Zappa and Beefheart were in America and completely unavailable. We tried to sign Cockney Rebel early on but were beaten hands down by EMI.”

However, coupled with the doyens of the “Canterbury scene”, Virgin founded their reputation on looking to Europe. They signed Faust, then Tangerine Dream – a far more commercially viable project.

“What really set Virgin apart from our rivals like Chrysalis and Island was that they weren’t so European-orientated,” continues Draper. “We were sustained by electronic and avant-garde music.”

He “vaguely” remembers his first playback of ‘Phaedra’, as recounted by Baumann and Froese.

“I did like ‘Phaedra’ a lot. The thing was, it was rhythmic. It was very atmospheric, very powerful and we knew it would sell, which is a huge plus. And it sold. ‘Phaedra’ went gold.”

So, for all the stress and jeopardy that went into its making, what was the end product? How did ‘Phaedra’ resonate then – and today?

“The common idea was to start very, very simple – one tone or pad,” says Baumann now of the group’s working method. “We started every concert like that, it was our signature. Instead of starting with a bang, start with the opposite – extreme simplicity – and see how it develops. When you improvise, someone throws something out, someone else responds. And no one knows what the outcome will be.”

‘Phaedra’ does indeed begin relatively simply, with a single tone falling like a meteor from a starless sky, twisting, silvery, reverberant. And then the sequencer stirring, within a few years an instrument whose ubiquity stretched to TV adverts, but which in 1974 was entirely novel, like nothing else – fresh metal from beyond Earth, an addition to rock’s periodic table, putt-putting into view like a UFO. The Moog sounds waver tantalisingly, an accident incorporated into the piece as if in praise of serendipity, while Gothic Mellotron adds to the instrumental chorus, weathered and ancient, as if having travelled light years to get here.

“It’s not a hi-fi recording,” says Steven Wilson. “And I think that’s why it has that fuzzy, hazy feel. Like when people talk about hauntology and things like Boards Of Canada, that slightly lo-fi, queasy thing, that sense of roughness and decay – it’s not hi-fi. The Mellotron is that by definition… this Heath Robinson contraption, these rusty tape loops, never completely in tune. All those hums, that hiss – you could consider it the first ‘hauntological’ recording. There was just an extraordinary sense of otherness about it that blew me away. It sounded so alien, like it belonged to a different century.

“When I heard the tapes, I was astonished to discover that this was essentially three people creating a mono sound – the multitrack tape has three channels on most of it, and each musician had a mono feed. So this idea of stereophonic sound – it’s a complete antithesis, in a way. It’s very lo-fi, very primitive. Every time they turned on the synthesiser they had to create their sound from scratch. And if the cleaning lady came in during the night and moved the knobs they were back to square one again.”

The mood shifts on the Froese composition ‘Mysterious Semblance At The Strand Of Nightmares’ as synths sweep diaphanously across a seascape, its classical meandering reflecting Froese’s belief that there was little to commend modern music, even among his own West German peers, and that only classical music truly reached the aesthetic heights of which he dreamed. Oceans boil over below – there’s a sense of space, of grandeur confected out of nothing.

On ‘Movements Of A Visionary’, the velocity of the sequencer goes up a notch, charting electronic territories hitherto unexplored, leaving spatial detritus floating in its wing mirrors. Organ-like phrases are a reminder of the ancient as well as the future, a music which somehow exists outside of rock altogether, channelled from a different dimension. Finally, ‘Sequent C’, Peter Baumann’s heavily processed recorder piece, takes you to a new space altogether, another mode, belying the taxing circumstances in which it was made.

‘Phaedra’ has been described as a precursor to dark ambient, though Froese deplored the idea of Tangerine Dream being regarded as background music. He demanded that it be focused on and attended to, undividedly.

“We are definitely not new age,” Froese told NME’s Simon Witter in 1990. “Although some of our music sounds similar to what is now called new age, it hit people in a way that made them active internally, it made them react and feel and think about their emotions. New age today is the exact opposite – it puts people directly to sleep. Our music was never for one second meant to make people drowsy or turn them away from reality.”

‘Phaedra’ sounds like nothing else and retains its sense of strange dissimilitude, precisely because it finds Tangerine Dream working on the threshold of new instrumentation.

“People were responding to new technologies and didn’t know the rules, the prescribed ways you were supposed to use things,” says Steven Wilson. “No one knew how to use the Mellotron. And that’s what is missing from a lot of 21st century music – that sense of not knowing the rules.”

To the group’s astonishment, the album was an instant but completely unexpected success.

“I was with my girlfriend travelling in Italy,” recalls Baumann of the weeks following the release of ‘Phaedra’. “Suddenly there was a telegram from Richard Branson – that was the fastest means of communication. It said, ‘You’ve got to come to London immediately, your record is in the Top 10’. And I remember, I read that and thought, ‘What Top 10?’. We’d never been in any kind of chart, certainly not the Melody Maker one.”

How does Baumann account retrospectively for the success of ‘Phaedra’?

“Well, quite frankly, I think it was luck – the circumstances just coming together to make up the best possible scenario. Christopher getting his Moog synth, getting away from the previous record label, Richard travelling to West Germany to sign us… a lot of luck involved. But most of all, it was the timing. The mood and the environment were right, and the sounds we created were absolutely unique. The constellation of Edgar, Christopher and me was great. None of us were musical geniuses, but we had a great sense of how the three of us combined could come up with something coherent and unique.”

Following the success of ‘Phaedra’, Tangerine Dream would have further dealings during the Virgin years as they made successive renegotiations of their contract.

“Richard is a crazy guy, as you know,” says Baumann. “He’s very likeable – a huge amount of energy. He just can’t sit still and jumps all over the place, making phone calls, sorting contracts, having a conversation at the same time. But you can’t sit down and have an in-depth conversation with him. He always had to come up with a new joke.

“We were once in Virgin’s offices discussing an extension of our contract. We set out our demands and suddenly he jumped out of the office window – a first floor office window. And then he came back up the stairs, wearing these pretend bandages and walking with a crutch, like he was badly injured. He would pull stuff like that all the time.”

Edgar Froese’s assessment of Branson, on the other hand, was somewhat sidelong and skeptical.

“It was an obvious fact that Branson wasn’t able to understand our music,” stated Froese in his autobiography. “He simply found it hip and thrilling if others reacted positively and enthusiastically, and he knew that this form of acceptance would be positively reflected in his bank balance.”

In the wake of the huge success of ‘Phaedra’, Tangerine Dream undertook a series of concerts, many of them in cathedrals, including a performance at Coventry Cathedral, which had been bombed 40 years earlier by the Germans – an irony that did not pass Froese by as they returned to the city armed merely with synthesisers. They were in some respects an anti-spectacle, playing with their backs to the audience.

“We had no fancy lights, we didn’t jump around onstage,” says Baumann, reflecting on it all. “With us, it was never personalised. No one really knew what Edgar, Christopher or I were doing. Music was at the centre of what we did, never us as individuals.”

However, there was something monumental about them – the combination of their cavernous sound, their often-ecclesiastical surroundings, banks of equipment and later, their light show.

‘Phaedra’ represented a zenith for Tangerine Dream, but some thought the group went into a gradual musical decline afterwards, as their use of electronics became more accomplished and therefore more conventional, an effect compounded by Froese increasingly using his guitar, dismaying fans like Steven Wilson – and ultimately making Simon Draper’s job rather more difficult.

“They found it easy to make music – our problem was trying to edit them and discouraging them from making so much music,” says Draper. “They were trying to produce two albums a year, but it got to a point where we thought it was better to release less work so that people were left waiting. There was too much material, especially with their solo albums… it was bad for their career.”

Still, 50 years on, ‘Phaedra’ continues to radiate. A vision of an absolutely new music, made in distinctly fraught circumstances under testing creative and technological conditions – a real sense of jeopardy, trial and error, and discovery – ‘Phaedra’ still circles the globe, a spectacle to behold, unrusted and undimmed.

For more, visit tangerinedreammusic.com