In the mid-1960s, Delia Derbyshire collaborated with playwright Barry Bermange on ‘Inventions For Radio’, a series of groundbreaking sound collages. Dr David Butler, curator of the Delia Derbyshire Archive, looks ahead to a forthcoming boxset of these pivotal radiophonic recordings

“Delia was working on ‘Inventions For Radio’ at the same time as ‘Doctor Who’, so this was a really intense time for her,” explains Dr David Butler. “She’d joined the Radiophonic Workshop in April 1962, and been eased in relatively gently. But by 1963, her reputation had really started to grow within the BBC.”

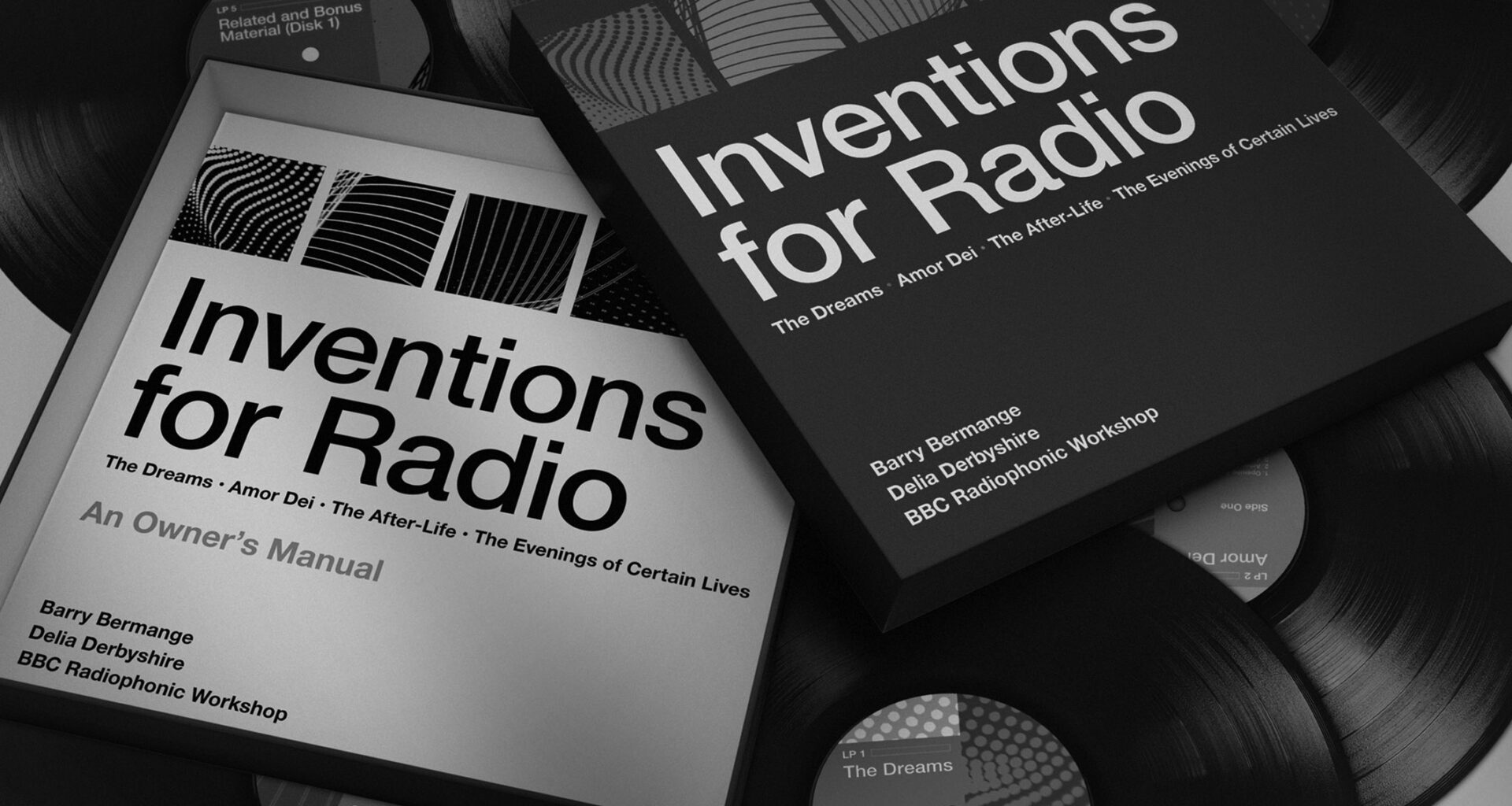

This year sees the first-ever official release of ‘Inventions For Radio’, a compelling series of sound collages broadcast by the BBC’s Third Programme radio service in 1964 and 1965. Initiated by playwright Barry Bermange, the series comprised four 45-minute instalments – ‘The Dreams’, ‘Amor Dei’, ‘The After-Life’ and ‘The Evenings Of Certain Lives’.

Bermange had collected field recordings of everyday Londoners and home counties residents discussing impressively weighty matters, from the nature of their dreams to their relationship with God and their ideas about the hereafter. Edited into meticulously assembled montages and combined with Delia Derbyshire’s sympathetic radiophonic accompaniment, they make for a touching and sometimes unsettling listening experience.

Butler, a senior drama lecturer at Manchester University, is a curator of the Delia Derbyshire Archive and the writer of a forthcoming biography about this most enduringly fascinating radiophonic trailblazer. ‘Inventions For Radio’, he says, forms a pivotal part of her body of work.

“In the 1960s, Barry Bermange was part of the absurdist theatre movement, alongside people like Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett,” explains Butler. “People were touting him as one of the next big things in British theatre, and he had some genuine success. He really is significant, and ‘Inventions For Radio’ wouldn’t have happened without him. But Delia did much more than was acknowledged.

“There’s a smoking gun. When ‘The Dreams’ went out, there was a memo from the BBC’s Head of Radio Features saying they’d been impressed by Delia’s work, and they were going to commission more from Barry Bermange. Desmond Briscoe, Head of the Radiophonic Workshop, wrote a note saying, ‘I would like to discuss Delia’s contribution to this programme… apart from the obvious electronic music’.”

The skilful arrangement of the speech snippets, says Butler, suggest Derbyshire was heavily involved in the editing process, seamlessly weaving metaphysical thoughts from the anonymous users of Hornsea Old People’s Welfare Council into her first truly long-form musical compositions. But the result wasn’t to everyone’s taste. BBC audience reports, collected immediately after the original broadcasts, include complaints from Third Programme listeners about “moronic mumblings” and “self-opinionated nonentities”.

In 2023, these reactions seem jaw-dropping. By anyone’s standards, the members of the public recorded for ‘Inventions For Radio’ speak with great erudition and articulacy.

“It tells you a lot about the listenership of the Third Programme,” says Butler. “The BBC Handbook itself says the Third Programme was seen as having a narrower audience – so you are going to get ‘disgusted of Tunbridge Wells’ in there. People who have working-class accents discussing the psychology of dreaming, or whether God exists? There seemed to be a feeling that they didn’t have the right to talk about those things. It should be a philosopher or a theologian, Aldous Huxley or Malcolm Muggeridge.

“It’s easy to over-romanticise that period. With films like ‘A Taste Of Honey’ and programmes such as ‘Coronation Street’, working-class voices were coming through, but it didn’t happen overnight and there were still prejudiced attitudes around. I think ‘Inventions’ taps into that, and that’s what makes it so remarkable and important.”

The series, Butler suggests, also captures a salient moment in Delia Derbyshire’s progression as a composer.

Devising her arrangements for ‘Inventions For Radio’, she drew on lessons she had learned at Dartington Hall Summer School – a residential course in contemporary music founded by William Glock, who became the BBC’s forward-thinking Controller of Music in 1959. A year before beginning work on ‘Inventions’, Derbyshire had helped to run a week of educational workshops delivered by a major figure in the electronic music field.

“In August 1962, Delia went away to Dartington and worked with Luciano Berio,” says Butler. “And Berio’s influence is definitely on ‘Inventions’ – especially the chopping up and transformation of the human voice. You can tell, when she comes back, that his ideas are flying around in Delia’s head. She references him in her notes, and she starts creating graphic scores after seeing Berio use them for his pieces. That experience was massive for her in developing an understanding of electronic music. Prior to that, she’d largely been learning on the job.”

With regard to ‘Inventions’, the relative credit afforded to Bermange and Derbyshire has, says Butler, shifted over the decades to reflect their respective reputations. In the 1960s, Derbyshire’s contribution – in accordance with BBC policy of the time – stayed anonymous, covered simply by a catch-all credit for the Radiophonic Workshop. Her first on-air acknowledgement prefaced a 1977 repeat on BBC Radio 4. But since her death in 2001, Butler suggests it’s Bermange’s vital contributions that have been slightly overshadowed by the surge of interest in Derbyshire’s work.

Nevertheless, he nods enthusiastically at the suggestion that ‘Inventions’ was a project deeply infused with Derbyshire’s own personality and her complex upbringing.

“One of the reasons she became so obsessed with music was that it offered an escape from the things that troubled her as a child,” he says. “Her parents bought her a piano when she was eight years old, and music completely took over her life. The doodles in her notebooks are often clefs or staves or piano keyboards, and there’s one page where she’s just written the word ‘music’ over and over – it’s like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining’!

“When Delia was six, her sister Benita died at the age of four. They’d been evacuated together and had a close bond – they’d barely returned home from the war. So it’s very revealing that a lot of Delia’s writing about music, both as a child and as a teenager, is repeatedly about its transcendent quality… the ability of music to take you out of this world and into another state.

“In ‘The Dreams’, ‘Amor Dei’ and ‘The After-Life’, it’s all there. I think these pieces spoke to her, and she was able to plug into things that had really informed her and her interest in music.”