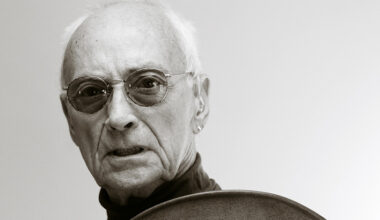

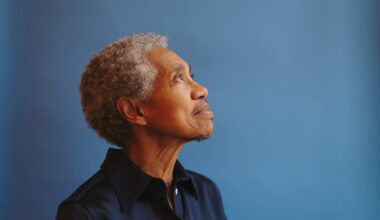

Slightly odd and very groovy Belgian synthpoppers Telex are getting ready for a renaissance. Having enjoyed their first success in the late 1970s, they are digging into their back catalogue to reissue a collection of their many highlights. And no one is more surprised than the group themselves

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here