With an eventful career that began in the 60s, Silver Apples have every right to enjoy a quiet retirement. But founder and lone surviving member Simeon Coxe is having none of it and has, instead, produced his magnum opus

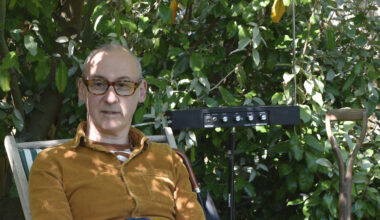

Silver Apples are one of the last acts radiating from the seismic revolutions which gripped New York City in the late 1960s. As sole surviving member of the world’s first two-man electronic band, Simeon Coxe is one of the few original electronic pioneers still pushing forward rather than trading on past innovations.

Defiantly, he still sounds like nobody else and, in a world that may have finally caught up, he has just released what is one of the landmark electronic works of the 21st century.

Remarkably, ‘Clinging To A Dream’ is the first full Silver Apples album since the late 90s. While boldly continuing the original mission of using primitive components to create space-age psychedelic dream soundtracks, the album dares to venture into compelling new sonic vistas as Simeon’s voice and oscillators shimmer in a lustrous alien greenhouse built with the help of Hackney-based producer Graham Sutton.

It’s oddly reassuring that, although Simeon recently turned 78, he can still raise such heavenly hell on the oscillator set-up he started building in New York City nearly 50 years ago. He still transmitting sizzling satellite globules and spectral melodies at a time when much electronic music seems in danger of letting technology do the heavy lifting while it replicates existing formulas into a new form of nostalgia.

Four of the songs on the new record are from an ‘opera’ I had been working on,” reveals Simeon. “It was conceived as a digital, animated saga involving a group of immortal beings who were at war with blood-drinking vampires for thousands of years. They thought the vampires’ breath stank because of the rotting blood and that they were basically disgusting. The immortals felt their purpose was to protect humans from this scourge. They had many beneficial encounters with humans without the humans being aware of them. The opera chronicled a series of these encounters. I felt some of the songs could stand on their own so I included them on the new record… the rest are from all over the place.”

The album starts with the lights coming up on a distant planet before the familiar bass motif of ‘The Edge Of Wonder’, previously unveiled as a single in 2012, pulses into life. In a strange way, Simeon’s quavering Martian nursery rhyme intonation recalls the fragile other-worldly innocence of Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd’s vastly misunderstood doomed genius who spoke from a world rarely glimpsed in music. In some ways Simeon is a fellow messenger, carrying on the mission of infusing pop music with endangered magic and sense of cosmic wonder.

As a long-time believer that the main ingredient lacking in most music is imagination, Simeon’s still seems to know no bounds; a principle reinforced by the queasy proto-techno stealth missile of ‘Concerto For Monkey And Oscillator’, with its radioactive bass snakes, corroded African piano riff and samples from what Simeon describes as “various animal sanctuaries” (shouting out to Amsterdam zoo in the credits). The album finishes with the demo of ‘The Edge Of Wonder’, which seems to have taken over from ‘Oscillations’ as a kind of Silver Apples’ theme song. It’s a fitting finale to this astonishing album, just Simeon alone with the invention he’s always called The Thing (others often refer to it as The Simeon), his one remaining friend from Silver Apples’ 60s gestation. The hazardous birth of The Thing is well documented but, for those just clambering aboard, it’s the electronic battle weapon Simeon started building a few years after arriving in New York City in 1960.

According to Simeon, he and The Thing have finally reached a degree of understanding after years of him having to deal with what he once described as “a temperamental diva”. For the first time, he feels he’s coming out on top after nearly 50 years grappling with her.

“I used to feel like the beast was steering me,” he says, “but now I feel like I’m in control. I’m finally learning how to play my creation.”

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, and growing up in New Orleans with piano pounders such as Little Richard, Fats Domino and Big Joe Turner ringing in his ears, Simeon had shone as an art prodigy as child. After hitting New York’s vibrant melting pot in his early 20s, he hung out at the Cedar Tavern on University Place, favoured watering hole of the Abstract Expressionists, beats and musicians.

“The Cedar Street bar was the artist hangout in the early 60s,” he remembers. “You’d go in there and see people like Bill De Kooning and Jackson Pollock. New York was an open-ended cauldron of creativity. You were not just encouraged to do something completely different and off the wall, it was almost necessary to get anybody’s attention. If you wanted to be taken seriously as someone doing something experimental, it had to be pretty blatant. We felt that way so that’s the atmosphere we were creating in.”

To try and sum Simeon up as just a musician is like trying to describe Alan Vega as a singer. Like the Suicide frontman, Simeon was an artist before he started making noise from electronic circuits. This artistic sensibility is a key element which informs Silver Apples and he has carried on painting and creating visual art ever since, including the new album’s striking sleeve.

In early 60s New York, many different forms of art co-existed and often spilled into each other. Simeon’s passion for groove-driven R&B dominated his first band, The Random Concept before he hooked up with local composer Harold Clayton who took him to jazz clubs, including edgy Alphabet City niterie Slug’s Saloon where synth pioneer Sun Ra was in residence for six years from 1966 and showed Simeon how far into the cosmos musical boundaries could be pushed.

Through Clayton, he met a musician called Hal Rogers, who introduced him to the influential 12 tone technique, which ensures the notes of the chromatic scale are given equal importance in compositions. It inspired many riffs and basslines later used by Silver Apples “and even today in my paintings, which are an aesthetic exploration of Chaos Theory”.

Simeon was fascinated by the World War Two oscillator Rogers had hooked up to his stereo. Although normally used in radio and TV transmitters, Rogers liked to get pissed and play along with Beethoven.

“I played it with an old rock ’n’ roll record and was absolutely hooked,” recalls Simeon. “That’s where my fascination with electronics came in. Without that I don’t know where I would have been. I eventually bought it off him for $10.”

In 1967, Simeon joined covers outfit The Overland Stage Electric Band, but his noise-generating contraption caused the whole band to flee in disgust, leaving just drummer Danny Taylor. Simeon found more oscillators in junk shops, which he used to construct a crackling, sparking tower that he controlled through operating 86 telegraph keys with his hands, feet and elbows.

The Thing was born and, after Danny joined in with his two drum kits, so was Silver Apples. The name came from Simeon’s teenage years immersed in Romantic poetry and an 1899 W.B. Yeats poem called ‘The Song Of The Wandering Aengus’ (“And pluck till time and times are done/The silver apples of the moon”). Along with Suicide, they were like lone warriors carrying space-age weapons when taking those first tentative steps in New York. After their first major gig in Central Park, Silver Apples played the downtown circuit, particularly Max’s Kansas City. Like Suicide would soon experience, Silver Apples provoked hostility and violence from crowds.

“People would shout because Suicide had no guitar,” recalls Simeon. “We got the same. They’d say ‘You’re not a rock ’n’ roll band unless you got a guitar’. I was very fortunate to have a drummer who was so good that an audience would identify with what he was doing and latch onto the rhythm.”

Alan Vega was one of Silver Apples’ earliest champions.

“They were so way out, man,” he once told me. “I loved the mini-malism of their stuff. I’d rave about the Silver Apples, but nobody had heard of them. We stole from the Velvets, Iggy, Question Mark And The Mysterians and Silver Apples. That music was part of us.”

Silver Apples’ first phase saw two albums, 1968’s self-titled debut and 1969’s ‘Contact’, which are now so frozen in timeless cryogenic suspension they can never sound dated. The plane-crash cover design of ‘Contact’ famously incurred the wrath of Pan Am, who smashed a legal boot down on Silver Apples effectively squashing any further activity. The duo had embarked on a third album, recording at the same time as their old friend Jimi Hendrix (who enlisted Simeon’s oscillators on the studio version of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ after the pair compared gadgets), but it never saw a release at the time.

The return of Silver Apples in the mid-90s was a joy. Prompted by a chance hearing of his old albums in a New York gallery some 20 years on from their release, Simeon resurrected the name and released two albums in quick succession, the Steve Albini-produced ‘Beacon’ and, consisting of just the one track, ‘Decatur’. Then, in 1998, he got a call from a radio station telling him they’d tracked down Danny Taylor.

“That was wonderful, that was amazing,” Simeon told Electronic Sound back in 2012. “Danny and I got together to play and it was like we’d never stopped. Someone rented him some drums and I took my gear up to his place and we set up in his living room. I said, ‘OK, what do you wanna do?’ and he said, ‘Let’s start where we started, let’s start with ‘Oscillations’’. So that’s what we did. It had been nearly 30 years, but it was like we’d played the night before at Max’s Kansas City.”

It turned out Danny had a rough dub of the unreleased third Silver Apples album, ‘The Garden’, which the pair reworked and made ready for release. By this time, the gigs were coming in. They’d played just three shows when, leaving a gig at The Cooler in New York, their van was involved in a serious accident. Simeon broke his neck in two places. That he survived at all was a wonder.

After two years in recovery, he was able to start playing music once more. But by this point, Danny was in poor health, having been diagnosed with a degenerative muscle illness. The gig at The Cooler in 1998 was the last time the pair played together. Danny died from a heart attack in 2005, by which time he was confined to a wheelchair.

‘Clinging To A Dream’ is Simeon’s crowning glory and also his ultimate tribute to Danny, whose beats still haunt modern sets as samples. Simeon recorded the new album at his home studio in Fairhope, Alabama.

“It literally used to be a chicken coop,” he says. “It’s behind my house and I just repaired some holes in the roof, put in insulation, and started laying down tracks.”

Which also explains why he calls his own record label ChickenCoop Recordings. The tracks were then sent to Graham Sutton, who harnessed, hotwired and beefed them up into the finished album. Sutton has an impeccable pedigree.

“It’s the same Graham Sutton who is in Bark Psychosis and worked with Jarvis Cocker,” says Simeon. “I basically gave him the raw tracks along with a suggested mix, just so he’d know what I had in mind. He also came to a few live concerts so as to get a better feel for the material. Then he went to work.”

As a result, Silver Apples has never sounded so good, or seemed so splendidly isolated in the electronic arena which, if it was a noisy, crowded playground, would see Simeon standing zen-like at its centre, bathed in dazzling luminescence, several feet taller than everyone else and beaming a beatific, unmovable smile. After all, after nearly half a century, Simeon has painted his masterpiece.

‘Clinging To A Dream’ is out on ChickenCoop