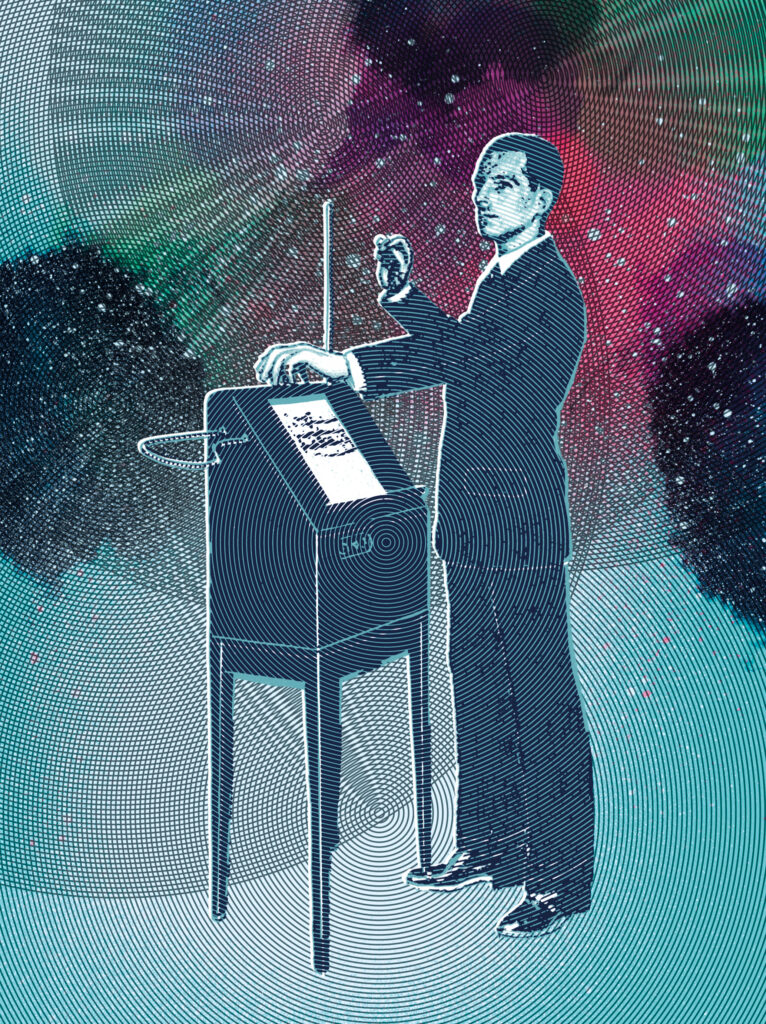

We’re setting the dials all the way back to 1927, to the Royal Albert Hall in London, where a packed audience gathered on a chilly winter’s evening to witness Russian scientist Léon Theremin using his remarkable black box to create “Music from the Ether”

Londoners passing the Royal Albert Hall on the evening of 12 December 1927 might have shivered to the sound of eerie electronic groans and bleats coming from the venue. Inside, a few thousand early tech-heads and forward-thinking music fans had packed the auditorium to capacity. Each had paid up to five shillings and nine pence to see the fêted Russian scientist Léon Theremin performing with his unique musical instrument. Theremin and his extraordinary black box had already thrilled concert goers in Paris and Berlin with renditions of works by Schubert, Saint-Saëns and Rubinstein. Now it was London’s turn to experience what was dubbed “Music from the Ether”.

The audience was confronted with what appeared to be little more than a plain valve wireless set, from which sprouted a vertical rod and metal loop. Soon to be named after its inventor, for many years the theremin was the only instrument that could be played without actually touching it. A circuit of oscillators, vacuum tubes and coils inside the theremin creates electromagnetic fields in the air between the antennae and these can be controlled by natural body capacitance. By gently vibrating your hands close to the antennae as if fingering an invisible fretboard, with a lot of skill and some patience, you can produce music.

The instrument was developed by Léon Theremin in 1920, while he was experimenting with radio apparatus to measure the dielectric constant of gases. Theremin, a sort of Russian renaissance man, was also intrigued by the possibilities of early television and the overlap of science and creativity, a space where sound and colour could be combined with geometric shapes, gestures, dance movements and the senses of touch and smell. He was a true multimedia visionary and his work soon came to the attention of the Soviet authorities. In 1922, he toured Russia to showcase his black box with the personal blessing of none other than Vladimir Lenin.

Two days before the celebrated Royal Albert Hall appearance, Theremin gave a private demonstration to a few critics and personalities in an upstairs suite at The Savoy in London. The dark-haired, handsome Russian appeared to the gathering more like a “diffident film star” than a scientist or a serious musician. In the front row, a fascinated George Bernard Shaw stared intently and, according to one journalist, “gripped the handle of his umbrella”.

Elsewhere in the room, the novelist Arnold Bennett was described as sitting rigid and surprised. For the larger audience at the Albert Hall, Theremin experimented with echo and used pitch to alter the colour of electric light. Those present were amazed, having said to have witnessed the future, or at least a new form of entertainment they could barely comprehend.

The day after wowing London, Léon Theremin boarded an ocean liner for New York. Despite an enduring loyalty to the Soviet Union, he spent the next decade in America, where the theremin was declared to be a magical device that heralded a new era in electronic music. In the post-war years, it was widely marketed as a novelty instrument, but many purchasers failed to tame its anarchic howl, eliciting sounds no more musical than a knife scraping a dinner plate. Most models were left to gather dust in the garage.

“One day, a man will come who can play much greater music than I can,” Theremin announced at the Albert Hall performance. In fact, it would be a woman, the virtuoso thereminist Clara Rockmore, who worked closely with him to popularise the instrument in America. Thereafter, in the 1950s, Bernard Herrmann took it to the cinema and its ethereal squeal was perfect for movie soundtracks such as Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Spellbound’. It was even used as a quirky addition to lounge orchestras. Eventually, everyone from Brian Wilson to Captain Beefheart to Kraftwerk warmed to the theremin’s good vibrations. Jimmy Page has long had a special fondness for it, putting it to good effect on Led Zeppelin’s ‘Whole Lotta Love’.

As for Léon Theremin himself, he returned to the Soviet Union in 1938, after 11 years on American soil.

According to his biographer Albert Glinsky, there were several reasons. “Walter Rosen, Theremin’s American patron, advised him to return to Russia to protect himself,” Glinsky says. “He was being tracked by the FBI. His company, Teletouch, was failing financially, and it was a front for Soviet operations in any case.”

Theremin landed in Moscow a free man, but his extended time abroad had raised suspicions with Stalin’s government. After six months back home, Theremin was arrested and spent the next 10 years in a labour camp, where he worked on surveillance technology.

When he was finally freed, he continued to develop a number of inventions and by the 1970s he was Professor of Physics at Moscow State University. In 1989, thanks mainly to the new Soviet spirit of perestroika, Theremin was able to travel to France for the International Festival of Experimental Music. It was the first time he’d been out of Russia since his repatriation half a century earlier. In 1991, now widely hailed as a significant figurehead of early electronic music, Theremin returned to America for a visit arranged with the help of documentary filmmaker Steven M Martin. The highlight of the trip, which took place two years before his death in 1993 at the age of 97, was being reunited with his old friend Clara Rockmore in New York.