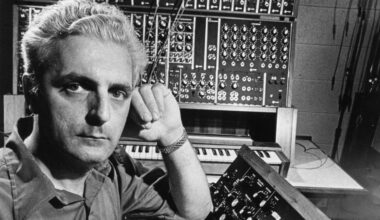

The astonishing story of Léon Theremin goes far beyond his famous instrument, taking in war, espionage, kidnap and, ultimately, redemption

Lev Sergeyevich Termen, or as he became known in the west, Léon Theremin, may not have led a charmed life. However, it’s fair to say it was not a dull one. His 97-year stint spanned a period of tremendous social and political upheaval, much of which would have direct consequences for Theremin.

Born in St Petersburg in 1896, as a young man he didn’t waste his time. By 18, he had already built a high-powered Tesla coil in the school lab and, having showed considerable scientific acumen, was running experiments using the local university’s facilities.

World War I interfered though and, once conscripted, he became a military radio engineer and later broadcast supervisor of a transmitter station (in what is now Pushkin), near the imperial house Catherine Palace.

Following the end of the war, like all of his countrymen, Theremin was soon deeply embroiled in the bloody Russian Civil War. The Bolshevik Red Army radio outpost Theremin controlled was a target for the opposing Imperialist White Army, who wished to broadcast falsified news of their victory in order to sway the masses. Theremin had other ideas though, and his last sight of the station was as he detonated the explosives that brought the outpost’s 120-metre radio mast crashing to the ground.

He eventually returned to his studies, working at the Physical Technical Institute in Petrograd on the invitation of prominent Soviet physicist Abram Ioffe. It was here, in 1920, that he developed the world’s first contactless instrument, which he dubbed the etherphone.

He began giving performance demonstrations of classical pieces utilising the musical ability he had developed playing the cello. A 1922 demonstration to none other than Chairman Lenin heralded his arrival in the Soviet big leagues. In 1927, Theremin was sent out on a propaganda tour of the West, ostensibly to showcase the wonder of Soviet technological advances.

He famously performed on the etherphone in front of an audience of thousands at London’s Royal Albert Hall and made similarly acclaimed appearances in Berlin and Paris, before heading to New York, where he would reside until 1938.

On arrival, he checked into the penthouse suite of The Plaza hotel and began interacting with the movers and shakers of New York society. While there, he patented and mass-produced his instrument, now rebranded as the theremin, in conjunction with US broadcast specialists RCA.

You’d be forgiven for thinking things were pretty rosy for the physicist at this point: another shining example of the American dream come true. However, Theremin was a Soviet scientist, and loyalty to Mother Russia came first. Attention from his homeland was, as such, a double-edged sword. Theremin’s biographer, the author and composer Albert Glinsky, maintains that Theremin’s real assignment during this period was in fact to support the development of the Soviet spy program.

Profits from the physicist’s activities were allegedly channelled into the country’s US/European espionage networks and Theremin was asked to send technological secrets back home. His interactions with RCA and even directly with the US authorities certainly left him well positioned to do so.

Nevertheless, it could be argued that he was not overly successful in this second brief. His courting of prominent theremin player Clara Rockmore (who turned down his several marriage proposals) and subsequent nuptials to African-American ballerina Lavinia Williams caused some scandal among the powers-that-be, presumably because he had arrived in New York accompanied by his Russian wife, Katia.

On 15 September 1938, Theremin left New York suddenly. Accounts as to why conflict. Some say tax issues, others, concerns over the approaching World War II. Williams, who never saw her husband again, maintained it was a kidnapping. One of Theremin’s dancers, Beryl Campbell, had reportedly called her to say he had left surrounded by a group of Soviet agents. His name was listed on the manifest of the ship, the Stary Bolshevik, as “the captain’s assistant”. Coincidentally, around that same time, the same ship participated in a covert Soviet weapons shipment for the Spanish Civil War.

Back in Russia, Theremin expected a warm welcome, but found he no longer curried favour with the political elite. The change in attitudes had severe consequences for the scientist. The authorities convicted Theremin of anti-Soviet propaganda, spread rumours he had been executed, then incarcerated him in a gulag near the East Siberian Sea leaving him working in the Kolyma gold mines. A chance of redemption arrived when he was moved to one of the secret “sharashka” laboratories that the Kremlin ran within the confines of the gulags.

Set to task working on spy tech for the NKVD (the secret police agency that would become the KGB), Theremin developed submarine tracking technology and an infrared microphone that allowed agents to eavesdrop through windows. The latter was a particular success and was used to spy on the British, French and American embassies in Moscow.

However, Theremin’s real espionage masterwork was a passive listening device known as “The Thing”. The bug was hidden in a hand-carved replica of the United States’ Great Seal, which, in a move of considerable guile, was presented to Moscow’s US ambassador in 1945 by a group of boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union (a sort of Soviet Scout group). The gift was hung in the ambassador’s office at the very heart of the embassy.

The genius of the device was that it contained no battery or wires – simply an antenna and a small silver diaphragm – and was operated by a remote radio signal. This meant it was extremely hard to detect. When Soviet spies wanted to listen in, they fired the correct frequency of radio waves at the device and the energy of the incoming beams was used to send the audio vibrations back. As such, it was 1952 – an incredible seven years and three ambassadors later – before The Thing was finally discovered.

By this point, Theremin was redeemed in the eyes of his oppressors. He was released from the sharashka in 1947, free to see out the rest of his days experimenting with physics and electronic instruments in various Moscow universities. On his release, Theremin was awarded the prestigious State Stalin prize. The irony of the fact that Lavrentiy Beria (head of the NKVD) had used Theremin’s inventions to spy on Stalin himself, was probably not lost on the scientist.