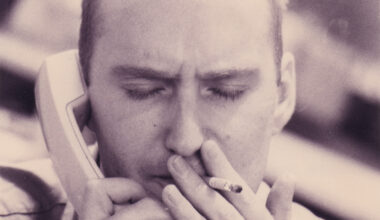

Talk Talk’s Mark Hollis famously retreated from the limelight long before his untimely passing in 2019. But a recently unearthed mixtape given to producer Gareth Jones reveals the early musical influences behind this most reclusive of artists

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here