Have you heard the one about Soma Recordings, the Glasgow indie dance imprint who signed Daft Punk and unleashed ‘Da Funk’ on an unexpecting world?

In a spacious flat in Montmartre, the kind you see in brochures, Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter has paper strewn all over the place. He wouldn’t normally litter his parents’ living room like this, but he is surrounded by faxes offering ludicrous record contracts. Multi-album deals, extensive worldwide tours, the stuff of dreams.

It’s 1996, the light is streaming through the windows, and watching him muddle through the paperwork are the two canny Glaswegians who made this happen: Orde Meikle and Stuart McMillan – the men who discovered Daft Punk.

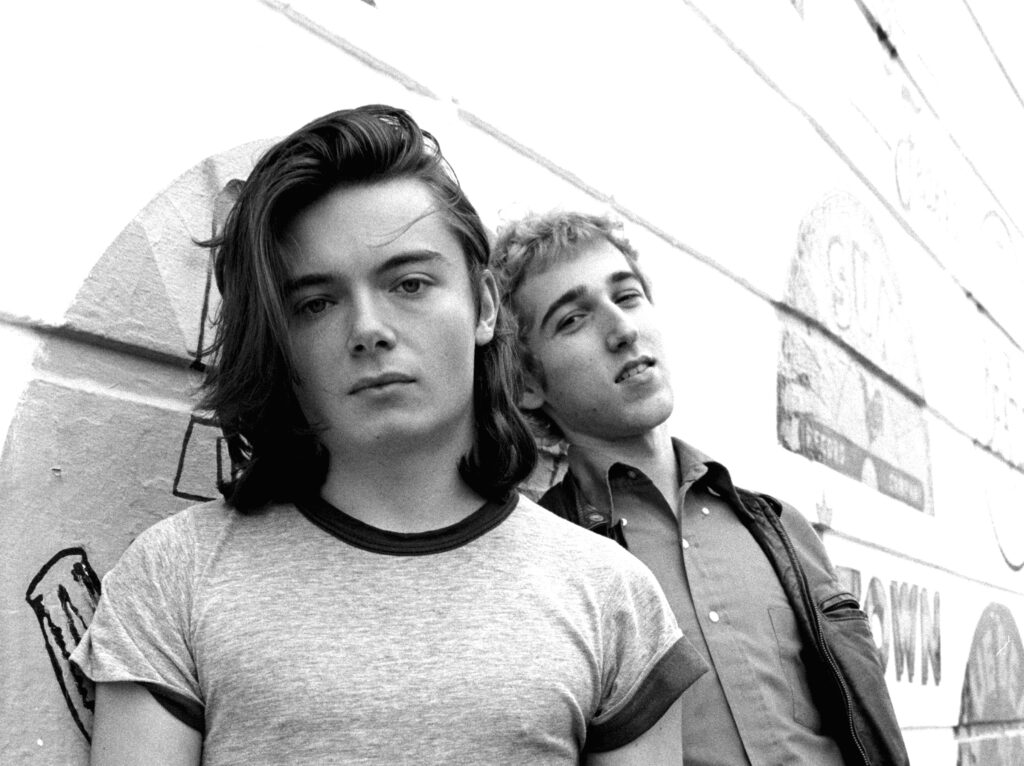

Rewind a few years to Chimichanga’s, a Mexican bar in the West End of Glasgow. The student district was prone to grotty theme pubs like this in the 1980s. Working at Changa’s brings in a wage for Meikle and McMillan, where they argue over what to play on the bar stereo.

“We used to jostle each other to put our C90s on the system,” says Meikle. “Stuart grew up through punk and soul music. I was very much into Jean-Michel Jarre, Kraftwerk and reggae.”

What the pair discovered was a passion for foisting their musical tastes on unsuspecting customers. When Scotland’s records shops began to fill with American techno from labels like Trax and Transmat, the boys swapped sombreros for slipmats. The Slam DJs were born.

“It was an industrial electronic sound that seemed to have its roots in soul music,” remembers Meikle. “We were instantly taken by it. Not enough of this music was being played in Glasgow clubs so we had a perfect platform to launch ourselves as DJs.”

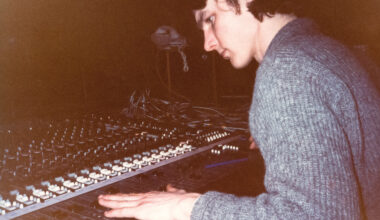

Slam’s Saturday night residency at the Sub Club, Jamaica Street’s basement dive of note, created a community of sweat-soaked technoheads. Fired by the homegrown vibe, Meikle and McMillan collared a couple of sound engineers who frequented their bar, Glenn Gibbons and Jim Muotune (the latter would go on to pen the theme tune to CBeebies show ‘Balamory’). Suddenly they had a band, engineers and, with the help of superstar techno bod Dave Clarke, their own label called Soma Records.

Despite visits to the Sub Club from the likes of The Stone Roses and the Pet Shop Boys, Meikle remembers the 1990 European Capital of Culture not quite being ready for pounding techno.

“Glasgow at that time was predominantly about rock music,” he says. “People were interested if you could play guitar and sell yourself to a major record company, they didn’t understand the ethos of electronic music. We had to do everything ourselves.”

That meant the whole process, from production to PRS, was left to trial and error.

“You could probably just watch a couple of good YouTube videos on it now,” adds Meikle.

The first Soma release was a split vinyl of Slam’s soulful ‘Eterna’ and the euro house of Gibbons and Muotune’s ‘IBO’.

“That was such a memorable day, going to London to get our first acetate cut. It makes me feel a bit queasy even now. We had no idea if anyone else liked it.”

They hadn’t even thought about branding, so Meikle and his mates hastily set to work designing a logo.

“I remember sitting in someone’s bedroom putting Soma stickers on the first 1,000 records, all hand-numbered,” he laughs.

In the early days they signed techno prodigy Ege Bam Yasi, Felix Da Housecat under the appalling Sharkimaxx moniker and, in embryonic white label form, Dot Allison’s One Dove.

“One Dove disappeared quickly into major record company land, but it gave us enough cash to be able to put the next two records out.”

Soma’s eighth release was Slam’s breakout single ‘Positive Education’. It was a genre-twisting deep house piece that reached corners of the globe far beyond the theme pubs of Scotland.

One of its acolytes was the 18-year-old Parisian Thomas Bangalter. His woeful indie band Darlin’ had been written off by Melody Maker as “daft punky thrash”. Bangalter turned that criticism on its head by forming Daft Punk with Darlin’ guitarist Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo.

Slam thought little of the note that came to Soma’s Glasgow office in summer 1993. Meikle remembers it saying something like, “Hi, our name’s Daft Punk and we really like the record ‘Positive Education’. We’ve got some tracks we’d like to play you”. Slam hooked up with Daft Punk at a rave in a field outside Euro Disney.

“It was instant,” says Meikle of the moment the Parisians played their cassette demo.

“Especially with ‘Alive’. We got three tracks in and we told them they were signed!”

Those demos became 1994’s ‘The New Wave’ EP, followed a few months later by ‘Da Funk’ whose plodding acid was so slow DJs had to bring sets to a virtual standstill to play the track.

“‘Da Funk’ was the one that lit the touch-paper,” says Meikle. “All of a sudden the phone started ringing: it was Parlophone and MCA and London Records…”

Back in the airy apartment in Montmartre, faxed contract offers everywhere, Bangalter plans to play record companies off each other to get the best deal possible. Daft Punk’s resulting move to Virgin, and a debut album with tracks licensed from Soma Records would rewrite techno history. Two decades later, their single ‘Get Lucky’ would go platinum worldwide. The turning point was that moment in Montmartre. Meanwhile, Slam retreated to their dark basements. They stayed at the Sub Club and pressed on with Soma, eventually releasing a rare Daft Punk remix on their new ‘Soma 25’ silver anniversary compilation.

“We met up with Thomas a couple of months ago,” says Meikle. “There was a lot of reminiscing how Thomas and Guy used to sleep on our sofas, how it was all very ‘bedroom’ and run on a shoe-string.

“Someone said to me recently that real techno is not a music that wants to be liked. It’s something to engage with in a dark, sweaty club at three o’clock in the morning. That’s when it makes sense.”