As Bentley Rhythm Ace prepare to mark the 20th anniversary of their self-titled debut album, Richard March recalls the early days of the band and reveals there was actually a (sort of) method to their (extreme) madness

They’d spend their Sunday mornings down at the car boot sales. Straight from the clubs, heads still jangling, they knew they could get breakfast, a bacon roll and a coffee, at the car boot. Then they’d embark on a good nose around.

“We would buy boxes of records for next to nothing, simply grabbing anything that looked interesting,” recalls Richard March. “We were real magpies and a lot of this car boot crap went on to form our first album. We would buy all sorts of bizarre stuff. We even paid a fiver for this ancient drum machine we thought we might be able to sample some loops off of. It wasn’t much use really, but it had a great name. The Bentley Rhythm Ace.”

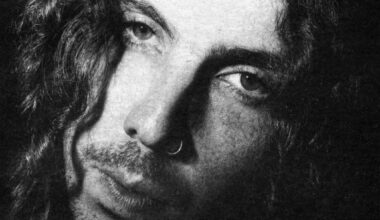

Richard March, the former bass player with Pop Will Eat Itself, formed Bentley Rhythm Ace with DJ Mike Stokes in 1995, releasing their self-titled debut album in 1997. ‘Bentley Rhythm Ace’ was a beautifully unhinged soundtrack to an imaginary movie which, had it been made, would probably have featured French students, awkward dinner parties and armfuls of drugs. A charming chaos of tempos, samples and genres, BRA bobbed along playfully like a sped-up lava lamp. Flutes, cuckoo clocks and air-raid sirens melded with drum ‘n‘ bass, acid house and out-of-context voices from who knows where, creating a universe both bizarre and faintly familiar.

“Pop Will Eat Itself was winding down at that point,” explains March of BRA’s origins. “There were five of us in the Poppies, with Clint [Mansell] and Graham [Crabb] being the main songwriters. However, Graham decided he didn’t want to be in the band anymore, so he went off to do his own thing. Clint then decided to move over to New York with his girlfriend for a few months and stayed there for about 10 years. So I started mucking about in the studio with Mike just for the sheer hell of it.

“We‘d walk around the Wholesale Markets in Birmingham having just left a club or we‘d venture further out to this car boot in a place called Studley, near Redditch. We‘d bag a load of records without knowing anything about them. Then we would sample some loops and generally mess about in the studio. I had access to this studio set-up in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, so Mike and I spent a lot of our spare time there towards the end of ‘96, putting together some tunes. We didn’t have any real intention of doing anything with them, but what happened was… well, it sounds like a ridiculous story.”

By the mid-90s, dance music had splintered into a multitude of genres and scenes. The chart pages of music magazines tried gamely to capture and define each and every sub-species. Handbag house or speed garage? Much easier to define were the post-dance scenes that drew upon and amalgamated many of these genres. Mixing left-field hip hop sensibilities with contemporary dance music and old funk, jazz and soul, much of this eclecticism fell under the rather opaque umbrella that was big beat, the slightly cheerier, more uptempo cousin of trip hop.

It was the time of early Ninja Tune, Skint and the Heavenly Social, along with the compressed disco sounds wafting in from over the Channel. There were nostalgic chimes in big beat, whether it was the surf rock riffs, the soul vocals or the wild jazz percussion mixing it up with contemporary ephemera from clubland.

“There was all this oddball stuff that didn’t really fit into the commercial dance scene,” March explains. “It wasn’t house, techno or drum ’n’ bass. It was quite left-field and odd, so you had all these people making stuff that didn’t fit into any sort of genre… and so it became a genre in and of itself.”

March and Stokes put together a demo tape featuring their favourite three tracks, which they played to friends and family.

“Well, Mike played them to a friend of ours who said, ‘I love ’em, I’ll send them off to a record label for you’,” says March. “Mike said, ‘But we’re not really sure which labels would be interested in them’. And so this guy wrote out a list of 10 labels and we sent the tape out to the first name on the list… which was Skint Records. They got back within a day or so and said, ‘We really love it, we want to put it out’. How mad is that?”

March and Stokes would spend hours sifting through their boxes of car boot tunes as they started work on a debut album, which was released after a couple of well-received singles.

“Bentley were re-using bits of other people’s rubbish really,” March laughs. “Anything we wanted, we recorded to DAT. We had bits from German commercials and keep fit records. ‘Run On The Spot’ samples a cover version of an old soul tune called ‘(Blame It On) The Pony Express’, which was on a tribute album to James Last. Now James Last’s cover versions were pretty bad, but this wasn’t even him!”

It was, in fact, the Tony Paterson Orchestra. Searching physically for samples was integral to the world of BRA.

“We were buying albums because they had an interesting cover or a ridiculous title, and because you’ve spent a bit of money you would search that little bit harder to justify the expense,” says March. “We loved the idea that you can take snippets out of context and juxtapose things that really shouldn’t work together. Both Pop Will Eat Itself and Bentley had that magpie approach to pop culture. The Poppies used lots of dialogue samples from TV shows, documentaries and movies, so the process was something I was familiar with. It’s not just a bunch of samples, we put a lot of work into it. There are programmed drum beats and synths in there and we had to get the balance just right so it all blended into a coherent sound… which was actually quite difficult to achieve.”

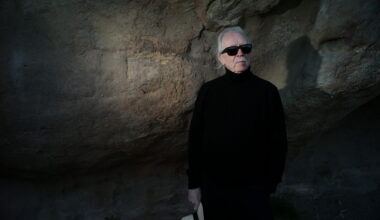

Richard March first started to get seriously into music aged 14 or 15, growing up with John Peel’s late night Radio 1 show.

“I was fascinated by experimental music,” he says. “I loved Robert Rental and The Normal’s ‘Warm Leatherette’ and Cabaret Voltaire. I also had older friends who were more into the techy side, with bands like Tangerine Dream. I loved the post-punk stuff of ’79 to ’81, with its aggressive sound and attitude. Some early Kraftwerk has a hard techno edge before they went towards the more polished and pleasant. I have always been interested in prototype technological music too, such as the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and Raymond Scott’s experimental stuff from the late 50s.”

BRA’s Top 20 single ‘Bentley’s Gonna Sort You Out!’, with its riff and vocals from a German striptease album (Orchester Werner Müller’s ‘Bodybuilding’ from 1972’s ‘The Strip Goes On’) was everywhere. Still is. It was a quirky little number, capable of conjuring up some rather odd mental narratives. It could have been an aftershave commercial from the 1970s. “Because the lady loves Bentley Rhythm Ace…”

“The track was used in adverts for Lynx and Golden Wonder crisps,” confirms March. “I got an email from the publishing company a few years ago saying that they had a request from Aldi supermarket for a Father’s Day special or something. I went home and told my wife and she was like, ‘Woah, will we get a new car?!’. She thought I meant Audi.

“A friend of mine also used ‘Bentley’s Gonna Sort You Out!’ for background music in lots of BBC TV shows, to the point where she got an email from her boss saying, ‘Can you find something else to use rather than Bentley Rhythm Ace?’. This girl was Mike’s landlady and I think she used it so she knew he was making enough money to meet his rent.”

Having achieved a not inconsiderable amount of success with a gold album and ‘Bentley’s Gonna Sort You Out!’ hitting the Top 20, there was a demand for Bentleys to perform live.

“We‘d never really planned it, so when we got some offers we thought really hard about how we were going to present this live,” says March. “Rather than dismantling the studio and setting it up every night, only to dismantle it again after, with an instruction manual in one hand and a screwdriver in the other, we went for a live band. I really didn’t want it to be two guys messing around with laptops and mixers on stage, and it worked out really well. We used to dress up in ridiculous outfits and put wigs on for that slightly camp element of performance.”

BRA took their live show to 28 festivals around the UK and across Europe in 1999 and 2000, including a number of spots at the Benicàssim festival in Spain.

“We were on after Richard Ashcroft and I’m a real fan of his, but it was pretty downbeat,” remembers March. “It was 2am, there were 40,000 Spanish people there who’d been drinking all day, and they had just been watching Richard Ashcroft, and then we came on stage and… well, the whole place went absolutely mental. It was a truly glorious moment for us. This little project had really become something.”

The live element was undoubtedly helped by March’s 10-year stint with the Stourbridge grebo crossover kings.

“Pop Will Eat Itself were a proper band and we toured a lot,” he says. “So I had a pretty good idea of what people wanted and expected from a gig.”

Another lesson March had learned from his days with the Poppies was that the music that mixed genres on record was not always welcomed when cross-pollinated with a live audience.

“We were asked to support Public Enemy and Run DMC in 1988 and it was one of the most ill-advised things the Poppies ever did,” March snorts. “We were fans and it sounded like a great idea. So we opened up for Public Enemy at the Brixton Academy, which was a huge honour for us. But the audience at Brixton thought otherwise. We did two nights there. The first night, people threw stuff at us, anything that they had to hand, like cups, bottles and rubbish. The second night they brought stuff with them to throw at us!”

After a hectic two-and-a-bit years of touring followed by some studio time, 2000 saw the release of the second Bentley Rhythm Ace album, ‘For Your Ears Only’. For many, it lacked the natural, homegrown feel of the band’s debut. It was as if the Bentleys had tried too hard.

The scope and ambition of the album were wider and higher, but it fell short as a result.

“The second album just didn’t gel the way the first one had,” notes March. “There’s some interesting stuff on there, but I wasn’t as pleased with the outcome as I was with the first.”

It’s been almost 20 years since BRA’s debut album, during which time Richard March has juggled live bands, studio work and teaching music technology to 16 and 17-year-olds at an FE college, as well as performing a bunch of dates each year as Bentley Rhythm Ace with Stokes and their old mate James Atkin, formerly of EMF.

“We still get a really amazing reaction live and the 20th anniversary of the first album has really got me thinking that it might be cool to get back into the studio with Mike again. Maybe it’s about that time…”