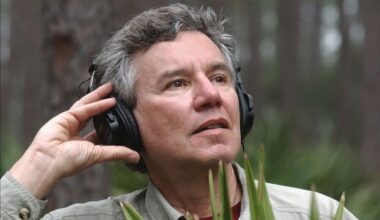

Four decades on from its release, ABC’s ‘The Lexicon Of Love’ is still one of the most luxurious and glorious widescreen pop albums of all time. Frontman Martin Fry takes a break from rehearsals for a 40th anniversary tour to tell the inside story of this enduring classic, starting in a toilet in a Tokyo hotel room…

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here