The comparatively modest, unassuming half of Yello, Boris Blank finally takes centre stage with a new box set handpicked from more than four decades of unreleased work

“I was never a musician, always more like a painter. My music with Yello was not so much a concept, but more a maze. The idea was to find interesting sounds on this planet, sounds which might lead somewhere. I built sound images out of noises, creating a world you could walk through, walk into the picture as if onto the set of a black and white movie. Each sound I make evokes pictures in my brain. In fact, an eminent scientist once said to me that because I am blind in one eye, maybe I have compensated with my ear.”

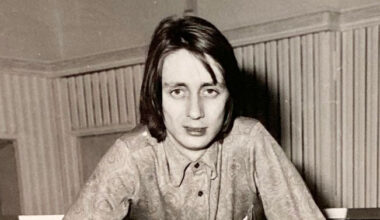

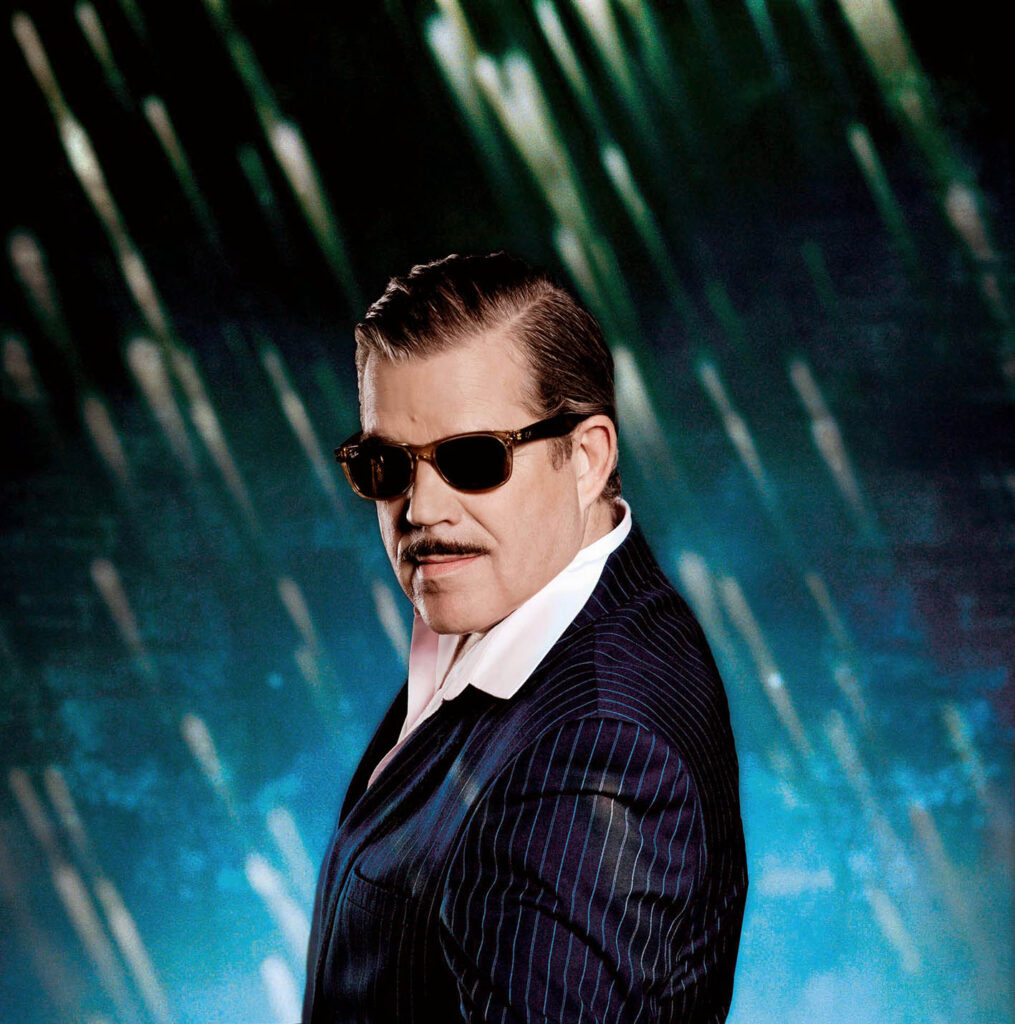

I’m talking to Yello’s Boris Blank, one of the grand old, larger-than-life characters of electropop, who has always been happy to remain in the shadow of a still more eccentric and gleefully ostentatious fellow, his Yello musical partner Dieter Meier – vocalist, master of ceremonies and Lord of Misrule. But now Blank is stepping into the light in his own right with ‘Electrified’, a box set of his unreleased work consisting of 60 (mostly) instrumental tracks dating from between 1977 and 2014.

What’s striking about ‘Electrified’ is how, even from his very beginnings and despite extremely limited equipment, Blank’s pieces have a visionary, applied quality, layered and ambient yet also multi-dimensional, as if recorded last week. Indeed, the whole collection sits in splendid, luxurious isolation from the electronica timeline. Despite Blank’s influence, and the homage paid to him by everyone from the Carls Craig and Cox to Matt Johnson, his music seems to belong in a lakeside castle of its own. Such a serendipitous surname as well. Blank – the empty canvas on which anything is possible.

Boris Blank is speaking to me by phone from the bar of a hotel in Switzerland, following an afternoon’s hiking in the Alps. Roman Polanski, he tells me, is sitting nearby. Throughout the interview, Blank keeps me apprised of Polanski’s movements, strolling from the bar to the terrace outside to take in the Alpine air and reminiscing about a convivial evening he once spent with the director at Les Bain Douches in Paris. The commentary lends a properly Yello-esque cinematic air to the proceedings.

Dieter Meier once told me that Yello were making soundtracks to unmade films, but despite the subsequent over-familiarity of that idea, in their day there was no one quite like this combo from the unlikely provenance of Zurich. Blank’s description of the open-ended, enigmatic scenarios through which the listener “walks” could not be more aptly applied than to ‘Lost Again’, in which literal footsteps emerge from a Noir-ish miasma.

‘Lost Again’ was released in 1983, at which point electropop was just starting to acquire a bit of colour in its wan cheeks but Yello were already in full, rich bloom. Meier set the mischievous tone for the group; a conceptual artist, some of whose pranks (such as laying a plaque in Kassel railway station promising to return to the spot on 4 March 1994) made him a living connection between Yello and the Dada movement, another great artistic bequest hosted in Zurich in 1916.

Yello were antithetical to the tinny, post-Kraftwerkian moroseness of late 1970s and early 1980s electropop, as well as its ostentatious sense of dystopian angst. There was an unapologetic, Technicolor opulence about them, as if, thanks to Meier’s legendarily wealthy background, they had access to electronic machinery unavailable to their cash-strapped peers. In fact, the real resources they had were Blank’s ear-magination and his prototype sampling techniques, as well as a shared, determinedly solemn sense of humour.

“Dieter and me, we don’t take life too seriously,” says Blank. “It’s good if you can laugh at yourself. But when I am working I am absolutely serious, completely on the case. I’m even called a perfectionist, which I don’t like, but I am a long time in the editing suite.”

Before his emergence as an exotic pop star, Blank worked as a truck driver. He had lost his sight in one eye as a child, when he’d been experimenting with gunpowder and bullet shells. He developed his interest in taping and manipulating sounds in his teens. He discovered electronic music, but wasn’t immediately interested in the steely, Germanic structures of the genre’s great pioneers.

“I was never a big fan of Stockhausen,” he admits. “For me, it was too academic, too calculating. I missed the soul. The same thing for Kraftwerk. I found it too sterile. But today, I understand that this sort of thing has its style, its appeal.”

Instead, he found what he calls his “electronic essence” through avant-garde jazz and psychedelia.

“Sun Ra, The Art Ensemble Of Chicago, Archie Shepp, Pink Floyd, King Crimson, Herbie Hancock, Peter Scherer… Then Daniel Miller and The Normal… I also loved classical things like Pierre Boulez and György Ligeti… A whole conglomerate of ideas, like a kaleidoscope.”

These were the ideas swirling in his head when he first met Carlos Perón and later Dieter Meier. For Blank, punk was not an epiphany, but a soon-to-be-obsolete cult, which he (literally) stepped over as he made his first recordings at the Rote Fabrik arts compound in Zurich in 1977.

“Punk was in fashion but nothing like in London, it was just a small scene in Zurich,” says Blank. “It was not something that interested me so much, though. I thought punk was finished after Iggy Pop’s first album. I remember the scene around Rote Fabrik when I went in to work there, with all these sleeping bags everywhere. It was like stepping over dead bodies.

“In my earliest days, I recorded onto quarter-inch tape, then cut the tape so that each length was the same, then played them faster and slower on the tape machine. This was my main equipment – that and a metronome, guitar, saxophone and bongos. Of course, eventually I got a Fairlight sampler, which was a big help.”

Following the release of their first single, ‘I.T. Splash’, Yello secured a deal with Ralph Records in America, home to late 1970s extremists such as The Residents, Tuxedomoon, Chrome and Snakefinger. Having signed to Ralph, Blank took out a bank loan and bought an Arp Odyssey, acquired because it was the instrument Herbie Hancock used on his 1973 album ‘Sextant’.

“At the local shop, they sold hardly any synths,” he explains. “It was mostly acoustic instruments, but after the success of ‘Solid Pleasure’ in 1980 they were like, ‘Hey, Boris! Come on in!’. Suddenly, I was very welcome.”

Never mind having a visionary take on electronic music, simply making the decision to play electronic music at all was considered visionary.

“I faced the usual things,” he sighs. “That electronics had no future, that it wasn’t ‘real’ music, you know, not like electric guitars… But then what happened to Bob Dylan when he first took out an electric guitar live? They called him Judas!”

The Ralph label proved to be an ideal springboard into the musical leftfield for Yello. They sat well in the early 1980s, an extraordinarily fertile time for wry funk, pop experimentation and electronic audacity, the time of Ze Records (Suicide, Material), Grace Jones, James Chance, The Associates, Thomas Leer and many, many more.

Yet even in this distinguished company, Yello stood out like a tuxedo among suits. It wasn’t just Meier’s surreally urbane self-assurance, but also Blank’s music, his manipulation of humble and improbable sound sources making even a belch sound as sleek and immaculate as an Aston Martin en route to Monte Carlo. A series of hits followed, including ‘I Love You’, and Yello’s place on the mountainous, peripheral firmament of avant-pop was sealed. They were sampling before sampling. Curiously, the next interesting group to do groundbreaking and astonishing things with that technology also came from Switzerland – The Young Gods.

“Absolutely, I love that group,” declares Blank. “I’m in contact with Franz Treichler [Young Gods frontman] and we’ve done interviews together. They’re one of the few really international bands from Switzerland and they are so unique.”

The Young Gods once sampled a Yello performance, ‘Live At The Roxy’, a well-received extended piece recorded in New York in 1983 that retains its electric majesty today. Blank admits that he has never enjoyed playing live, though. Despite Meier’s extrovert character, touring was just not Yello’s bag.

“It was never my way,” says Blank. “It always felt a bit cheap to be shaking your ass onstage and pretending to play live, because the music I make, and the way I make it, can’t be reproduced onstage. I never care to see people like the Pet Shop Boys pretending the music they play ‘live’ is actually live. Also, I’m not the sort of person who likes to be exposed in the middle. I prefer the studio. Dieter is different, of course. He is a natural entertainer, he enjoys the attention of a crowd. I’m an entertainer too, but only really with people I know.”

By the mid-1980s, Yello were attracting some prestigious guest artists, including Billy Mackenzie, who became a frequent collaborator, and Shirley Bassey, who they persuaded to lend her chandelier airs to the ballad ‘The Rhythm Divine’.

“Shirley Bassey was very professional,” recalls Blank. “I picked her up at the airport in my Lincoln Continental 8.7-litre car. These days I am more economical – I drive a fantastic Volkswagen electric car. Shirley sang the track twice, then we went into the garden of Dieter’s house for pictures and had sushi. Billy Mackenzie also came to Zurich and that was an intense time. He was such a very fast worker, he’d respond immediately to music. I’d play something and within two or three minutes he was ready with a lyric to jump in front of a microphone and sing. But he was very shy and he was so nervous watching Shirley Bassey record, he stood with me but then had to leave after 10 minutes.”

Following their biggest hit, ‘The Race’ in 1988, the subsequent decades were less commercially kind to Yello. The faded superstar Norma Desmond remarks in ‘Sunset Boulevard’, “I was always big – it was the pictures that got small”, and so it was with Yello. They have always been big, it is the pop decades that have got small. That said, both Boris Blank and Dieter Meier remain active and have a formidable legacy that keeps them utterly relevant to the 21st century. Check out, for instance, the Yellofier app, which has had well over 100,000 downloads to date. True to Blank’s modus operandi, you can use it to sample any sound, manipulate it, and build it into a Yello-esque, rhythm-based track.

“The entire planet is your palette, all for the price of a cup of tea!” enthuses Blank. “I think we should all believe in the future of electronic music and its future equipment. Even today, you have people stuck on analogue… But studying the architecture, all these new-plug-ins, the architecture of this instrumentation, keeps me young. Yes, we should believe in the future.”

Boris Blank’s ‘Electrified’ box set is out on Blank Media