Robin Wood, from teaboy to salesman to CEO

Robin Wood’s EMS association is a wobbly detuned synthesiser version of the classic postroom-boy-to-CEO story. From a humble first job as a general gofer for Zinovieff, to owning the company, Robin Wood has had the longest connection to EMS of anyone who was involved.

In September 1970, when Wood was about to turn 18, he discovered a friend’s sister happened to be married to Peter Zinovieff, who offered him some temporary work. He wasn’t, however, an electronics obsessive.

“I was more interested in electric guitar music,” he says. “I was interested in equipment, but not to the point that I was any good at taking it apart. I wanted a guitar amplifier, but when I got one that didn’t work, I was a bit flummoxed.”

A typical teenager, with a record collection full of The Doors, Hendrix and Pink Floyd, Wood joined EMS as a “general dogsbody”. His very first task was to help move the contents of Zinovieff’s studio from the shed at the bottom of the garden into the house at Deodar Road.

“The studio was amazingly advanced for the time, with its custom-made circuits all under the control of a very early computer, the PDP-8,” says Wood. “I had no idea what it was at all. It totally mystified me. I would tidy up the studio, and Peter would be working there all through the night, with reams of printouts coming out of his Teletype, and compiling programs to actually create music.”

By 1971, EMS was buzzing with activity. The business, alongside the research and development, was being run out of Zinovieff’s Putney home, with David Cockerell working his magic at his own workshop in Cricklewood. The synthesisers themselves were manufactured in a factory in Wareham, Dorset, run by brothers Jerry and Brian Rogers.

“The office was in the house, where Zinovieff lived with his wife and three children,” says Wood. “There were also couple of secretaries in a room at the top of the house. Tristram Cary was always in and out, although he didn’t use the studio because he had his own place in Suffolk. One of my jobs at the time was driving, and I would carry stuff to and fro between David’s place in Cricklewood and Putney.”

It soon became too much for both David Cockerell’s premises in Cricklewood, and for Deodar Road, and so expansion came in the form of two shop leases.

“David needed to have more engineers working for him,” says Wood, “so there was a little commercial premises rented at 46B Cricklewood Lane. Similarly, Putney became too mixed with Peter’s domestic situation, so a lease was taken on a shop in Putney Bridge Road, which was less than 200 yards from his house. And then there were more people; an accountant, some salesmen, a demonstration room, the servicing department in the basement, a flat at the top, where our German agent used to stay, and more secretaries.”

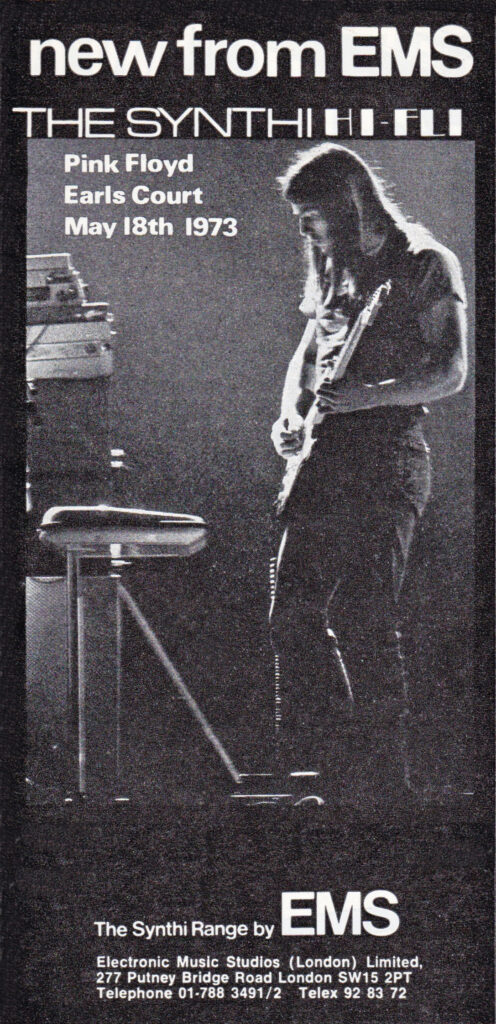

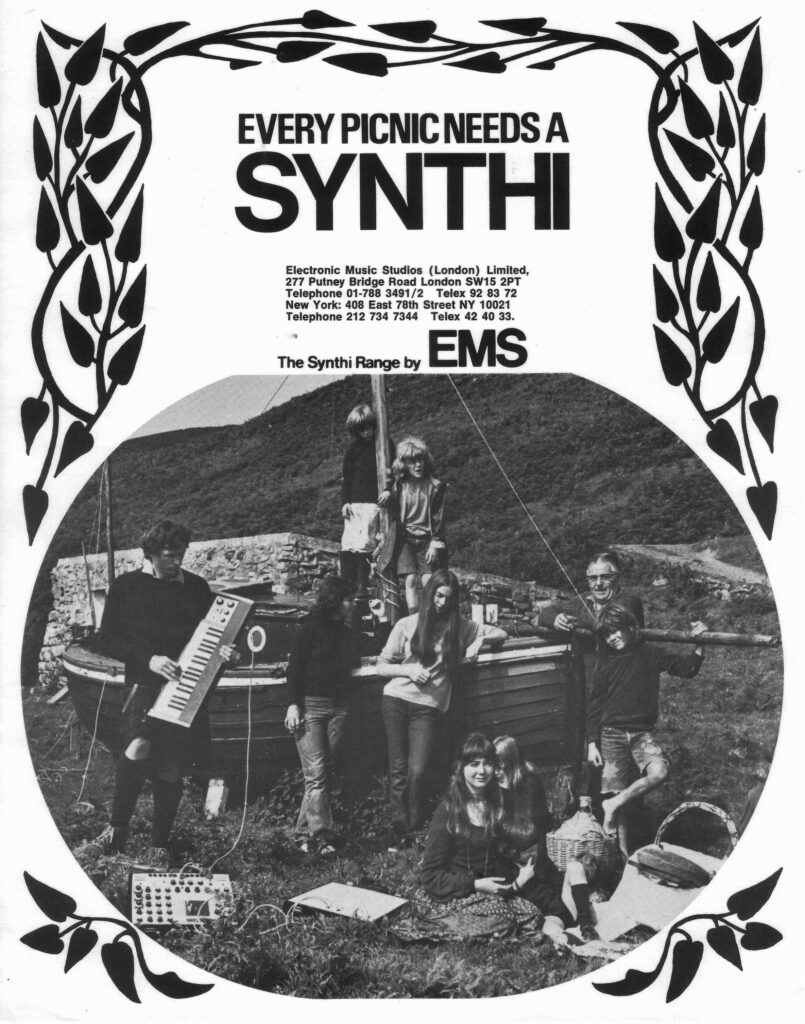

The first half of the 1970s were the peak years of production at EMS, with more products coming onto the market, like the Synthi A, the Synthi AKS, the massive Synthi 100, the Synthi Hi-Fli, a sequencer and various modules. The factory in Dorset was by now employing 25 people. As the company grew, so did Wood’s role. He was based at the EMS shop on Putney Bridge Road, giving demonstrations of gear.

“I would do technically limited demonstrations,” he says. “I’m not saying that I was particularly wonderful at it, because I can’t play keyboards, so I couldn’t impress them with keyboard licks. It was still early days for me learning how to get really interesting sounds out of the synths.

“That whole genre of electronic ambient noises was still in its early stages with people like Tim Blake of Gong, who was in a leading vanguard of those using the synthesiser for washes of sounds. People hadn’t really woken up to the fact that these machines were really great at producing that sort of stuff. They were only just getting their heads round it, including us. We were still thinking, ‘Our synthesisers are no good! They go out of tune! They’re difficult to play! We must have them more pre-programmed’.”

Despite the patronage of Pink Floyd, Brian Eno, Kraftwerk, Jean-Michel Jarre, King Crimson, Hawkwind, Gong and all the other progressive and art school bands of the early 70s, EMS sold most gear to educational establishments.

“Our best customers were schools and universities, not bands,” says Wood. “And if you were in London, the schools all came under the Inner London Educational Authority, or ILEA, and the VCS 3 and the AKS were in their catalogue of items that schools could order. Lots of schools thought, ‘Ooh, we’ll have one of them’, bought one, and the teacher who ordered it would use it. But when they moved on, the next teacher would come along and had no idea what to do with it. As a result, a lot of them ended up in cupboards in schools, from where they were either recycled into the music performing community or eventually thrown out.”

Was there a sense that the VCS 3 was the ideal educational instrument because it somehow combined lessons in music and an understanding of the physics of sound?

“I’m not sure about that,” says Wood. “My sense is that there were music teachers who were switched on, who came from that 60s generation, and they made a case for their school to get a synthesiser. Presumably there were also music teachers who weren’t switched on, who also had the budget, and thought, ‘Well, let’s get one and see what happens’.

“The actual music syllabus was still terribly traditional. No one knew how to structure activities around these instruments. But I didn’t have a great insight into music education at all, I just felt that it was down to individual teachers to get behind it and do what they wanted to do.”

Wood’s role as demonstrator extraordinaire took him to trade fairs in Europe and America, like the Musikmesse in Frankfurt and NAMM in Chicago and Atlanta. But even as the life of a synthesiser demonstrator became exciting and glamorous, and catapulted him beyond the environs of Putney and Cricklewood, there were storm clouds gathering.

Roland and Korg were starting to have some success with their synthesisers. Their machines were more stable and often cheaper than the idiosyncratic EMS synths, and their business practise was far more focused and efficient.

“EMS was certainly run in a very unconventional way,” says Wood. “It wasn’t run by men in suits, it was always focused on Peter’s studio. Indeed, the whole reason EMS started was to finance the studio, the idea was to make a bit of money selling synthesisers that would then be used to put into the studio and produce even more fantastic computer-controlled machines. It wasn’t intended for production at all, just one-off monsters for Peter. And then he offered them to be used by composers, like Harry Birtwistle, and Hans Werner Henze.”

The original trio of EMS founders broke up when Tristram Cary departed for Australia, and David Cockerell took up offers of work at Electro-Harmonix in New York and IRCAM in Paris.

“Pretty soon, EMS ran out of money,” says Wood. “There was always tension with the factory, because they didn’t really understand what was going on, or what Peter was up to with his studio. They were just thinking, ’Where are the orders and where is the money? When are you going to pay for the synthesisers we’ve supplied to you?’. And so there was a succession of factory managers who usually departed in unhappy circumstances.”

Zinovieff was still innovating, and had developed a 60-channel digital analyser, which worked like a vocoder, in which is the evidence of just how far beyond the world of synthesiser and electronic music his mind was working.

“He had a vision of using this amazing machine as a communications technology,” says Wood. “The idea was that you would encode speech and send it down digital lines, across continents. At that time, telephone lines were very noisy and expensive to use, but with digital there was a feeling that you could cram much more data down these wires so it would be cheaper to use.”

He was, of course, bang on the money, but the world of digital communication technology wouldn’t become commonplace until the 1980s, and it wasn’t EMS technology that powered it. Financial woes at EMS were about to pitch the company into its final spiral into bankruptcy.

Zinovieff had met a US-based businessman called Robin Leach on a flight, and Leach expressed an interest in financing EMS to allow it continue its pioneering research. By the end of the journey, the pair had agreed to all manner of schemes, and Leach (who later would find fame as the presenter of the US TV show ‘Lifestyles Of The Rich And Famous’) undertook to guarantee the substantial overdraft maintained with the NatWest bank.

When EMS breached their overdraft limit (again), the bank called in the guarantee, at which point it was discovered that Leach’s backing wasn’t so copper-bottomed.

“This was around 1976,” remembers Wood. “By that time, our German agent Ludwig Rehberg had a very healthy business supplying Synthis to Austria, Switzerland and Germany. He raised some money to bail EMS out of that little disaster, so then he became very influential within the company.”

All was not well on the domestic front either. Zinovieff and his wife split up, and the house at Deodar Road was put up for sale. EMS and Zinovieff relocated to Great Milton in Oxfordshire and Wood went too.

The next disaster for EMS was their attempt to keep up with the burgeoning poly synth market. Roland had launched the Jupiter-4, and Sequential Circuits had the Prophet-5, and so in order to keep up, EMS launched the Poly Synthi. It wasn’t a success.

“Peter and I went to New York to visit Electro-Harmonix and buy 100 Memory Man boards to put in the PolySynthis to do chorus and echo,” says Wood. “I remember we came back with a huge box of PCBs, and Peter also bought [Electro-Harmonix boss] Mike Matthews’ Memorymoog.

“We turned up at JFK check-in with an unwrapped Memorymoog. They weren’t fazed by it. They had these little cardboard things that they used to put around suits, a little flimsy cardboard sleeve, so we put one over each end of the keyboard and a bit of parcel tape and then it trundled off down the conveyor belt. It arrived at Heathrow, there were a couple of keys missing, but it was otherwise unscathed.”

Turns out that they didn’t need 100 Memory Man PCBs for the PolySynthi as it only had a limited production run.

“The PolySynthi sounded very odd,” says Wood. “It was very strange, very unreliable. It was very heavy, very big and too expensive, so only 50 were ever made. Not only that, but punk had happened, the whole direction of the musical establishment seemed to heading away from the experimental area where EMS instruments had proved themselves to be quite handy.”

The final straw came in 1979. Rehberg wanted to have a greater stake in the company for having bailed it out, but Zinovieff was reluctant to let him in. Suffice to say that the dispute escalated, large factory orders were made, bills remained unpaid and the bank foreclosed once and for all. The whole thing, in Wood’s words, “came tumbling down”.

The EMS brand was sold to a company called Datanomics, who continued to make the VCS 3 and Synthi A and they even redesigned the Synthi 100, selling just one. Datanomics struck an agreement with Mick Johnson Music, a PA company, who became the UK outlet for EMS gear and took on the lease of the Putney Bridge Road shop.

“I was employed for a short period by them in my established role as the person who knew what the equipment should do, and knew most of the people around the world who were selling it,” says Wood, “so I was in a good position to encourage people to buy them.”

When Mick Johnson Music went bust, Datanomics decided to get out of the synth biz. In 1984, Wood took on the EMS shop lease and kept himself busy taking phone calls from schools whose Synthis were starting to go wrong and needed their machines servicing.

Tim Orr, who had designed the EMS Vocoder and the yellow-faced Synthi E and happened to live nearby, generously gave Robin advice on the wiring in and outs when needed.

When Datanomics sold EMS in 1984, it was snapped up by Edward Williams. Williams was the original composer on the first series of the BBC’s ‘Life On Earth’ and he had a strong interest in electronic music.

Robin worked with him developing and manufacturing a MIDI controller called Soundbeam under the EMS brand for use by people with special needs.

“The first one had EMS on the front,” says Wood, “and then the SoundBeam 2 had EMS on the back in small print, and then the Soundbeam project became a force in its own right. I stopped working for them in 2012. Now it’s a standalone company, run by Edward Williams’ son.”

Wood himself took ownership of the EMS brand in 1994, and today there are two people working full-time making VCS 3s and Synthi As. They make around 20 units a year, and there’s a waiting list of over three years. The current price for a VCS 3 is £5,850 plus VAT. He’s phlegmatic about the various VCS 3 clones on the market.

“The only thing you can protect are trademarks,” he sighs. “You can’t protect the IP, you can’t say, ‘Well, if it’s got a matrix, and it looks like this, then it can’t be copied’, so that’s what’s been happening. We’ve been ploughing on regardless.

“We have licensed to a couple of people. A company called Digital, are doing the Hi-Fli, and we’re also co-operating with him on re-releasing some of the old modules. Then there’s Jonny Trunk of Trunk Records fame, he has a licence for the iPad VCS 3 app. But otherwise people just seem to be helping themselves. I’m not happy about it, who would be?”

Nevertheless, the oldest synthesiser company in Britain still exists, and is still making synthesisers, under the guidance of someone who has been with the company in one way or another since its inception.