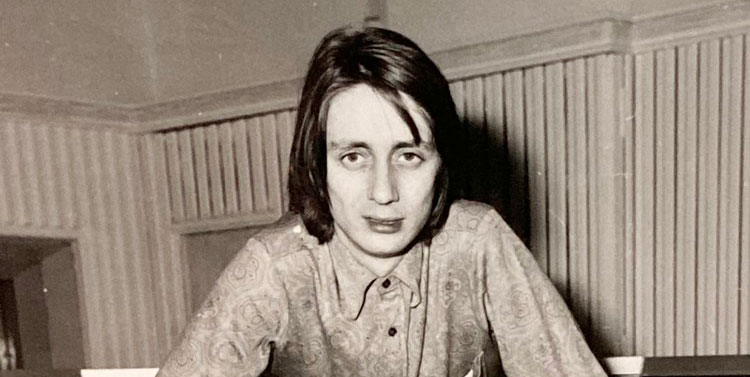

Released in 1971, Hans Edler’s ‘Elektron Kukéso’ album step-programmed its way into the future, at a time when computer pop was still a sci-fi pipe dream. And it’s an enduring delight to this day

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here