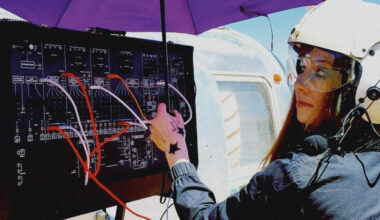

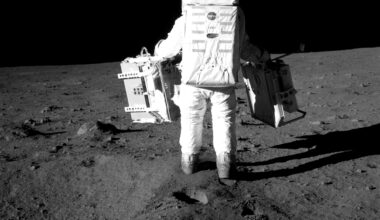

‘Music For Stowaways’ remains one of the most innovative and important electronic albums of all time. And the story of how it all came together has some pretty incredible twists and turns…

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here