For more than four decades, African Head Charge have pushed the outer limits of dub, concocting an intoxicating brew of electronic exploration and live percussion. Their latest long-player continues to confound expectations – from Accra to Ramsgate and back again

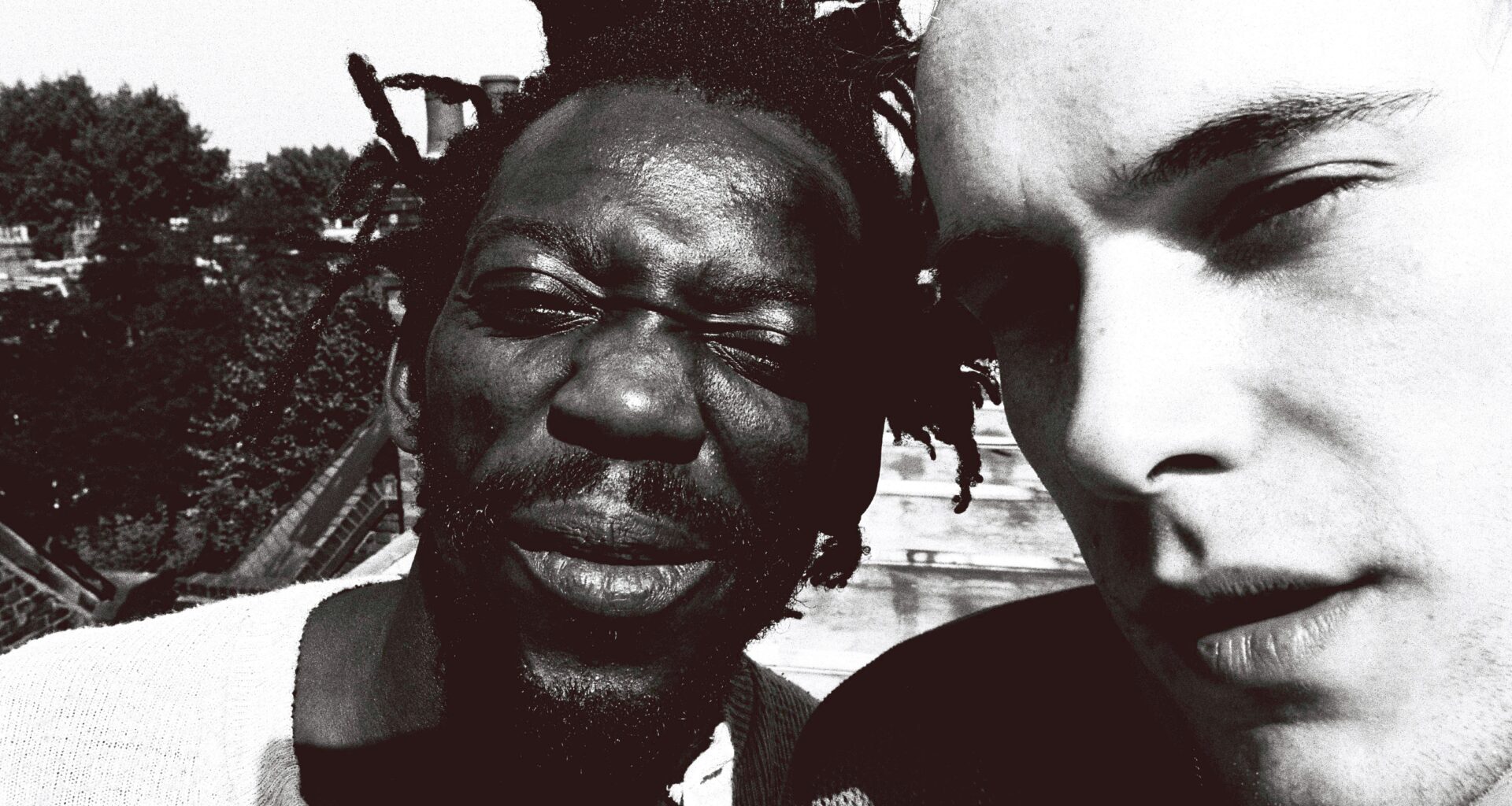

There aren’t too many artists who can say, straight-faced, that they’ve made their best record 42 years after their debut. But listen to the fervour with which Adrian Sherwood and Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah discuss their latest offering as African Head Charge, and you’d be hard-pressed to disagree.

‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’ is the pair’s first studio album in 12 years. It’s a varied and vital distillation of dub production, electronic trickery, spiritual uplift and deep percussive rhythms recorded in Ghana, where Bonjo now resides.

“We’ve got all the ingredients we’ve ever wanted to instil in our work on this record,” Adrian insists. “That’s why it’s so monumental. I think it’s a…” He catches himself. “I don’t want to swear, but I think it’s an absolute masterpiece. We are very proud of it.”

Perhaps one of the reasons he’s so vociferous in the record’s defence is because African Head Charge remain overlooked and undersold. Since their 1981 debut, ‘My Life In A Hole In The Ground’, he and Bonjo have cut almost a dozen studio albums and released numerous compilations, collecting the fruits of a four-decade friendship built on a foundational belief in experimentation that stubbornly refuses to fit any mould.

And while ‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’ is recognisably African Head Charge, there is a looseness to this project which feels both revitalised and revitalising. Gone are the monochrome industrial sleeve designs, to be replaced by a shocking pink colourway. “A bad attitude is like a flat tyre,” preaches the opening track. “You can’t go anywhere until you change it.” This is a joyous record, and the pair want the world to feel it.

Despite having built an obsessive following off the back of the band’s wide-ranging catalogue and some truly memorable live shows, Adrian finds himself disagreeing with friends who have joked that his persistence in the face of wider indifference is a sign of madness.

“I don’t think I’m mad because I keep working the same area with African Head Charge,” he says. “I can never understand why it hasn’t sold 10 times or 100 times more.”

Not that selling records was ever really the point. African Head Charge began as they meant to continue – the logical consequence of a mutual respect between two very different musicians who were making it up as they went along.

Barely 21 years old, Adrian Sherwood had fallen into production by accident, spending £200 to make a record with reggae outfit Creation Rebel and selling it from the back of his van. Friend and squat-mate Ari Up of The Slits called him “a hustler in the truest sense”.

He taught himself studio engineering and then live mixing while on a job with Prince Far I. By 1980, he’d founded On-U Sound and was well on his way, dipping between the worlds of dub and post-punk on albums like ‘The New Age Steppers’, which featured Ari Up and The Pop Group’s Mark Stewart, among others.

Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah, on the other hand, had a turbulent upbringing in Jamaica, running away from home and finding his people in the Clarendon Rasta camp in Kingston, where he absorbed the chants and rhythms of Kumina and Pocomania without knowing where his skill as a percussionist might lead.

Arriving in London as a teenager, he found himself hanging out at Ginger Baker’s place with Sonny Akpan from Nigerian rock group The Funkees, listening to the music of Osibisa and Mongo Santamaria, and integrating Afro-Cuban rhythms into his playing. Ushered into Fela Kuti’s touring band in London (it was Kuti who christened him “Bonjo”), his path converged with Adrian’s on Creation Rebel and the pair have never looked back.

As their first album professed, African Head Charge did indeed emerge from a hole in the ground – a basement studio on Berry Street in London’s Clerkenwell, to be precise. Adrian and Bonjo would ensconce themselves there for hours at a time, running rhythms through outboards and channelling the cut-and-paste approach of William S Burroughs and Brion Gysin into analogue tape loops and dubbed-out delays.

“One thing I like about Adrian is that he is willing to listen and encourage you to improve on what you do,” Bonjo says.

Where others avoided the low-end clash of big drums and bass weight, Adrian pursued a much heavier sound, egged on in no small part by Mark Stewart who, he says, “did more than anybody to push us off-centre, because he wanted something more extreme”.

Layered with field recordings captured in the Lake District, down-tuned Prince Far I cuts and Bonjo’s percussion, Adrian assembled ‘My Life In A Hole In The Ground’ – a tongue-in-cheek response to Brian Eno and David Byrne’s ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’, whose “visions of a psychedelic Africa” had inspired the African Head Charge name to begin with.

Adrian calls it a “charming, fun record”, but others – including the likes of veteran reggae DJ and tastemaker David Rodigan – didn’t fully appreciate what African Head Charge were doing. Nevertheless, they were determined to plough their own furrow.

“We thought if we fitted in, we’d just sound like everyone else and people wouldn’t notice us,” Adrian explains. “We wanted to stand out from the pack.”

“When you’re working with someone, even if it’s just two of us alone in the studio and you’re having fun for however many hours, it’s a great thing,” Bonjo considers, evidently keen to give Adrian his due. Few working partnerships last 40 years, let alone can still be called friendships after all that time.

“I think he’s the only producer like that,” Bonjo adds, breaking out in a big smile. “I shouldn’t talk like that in front of him.”

Throughout the conversation, the closeness of the pair’s relationship shines through. Sometimes they’ll finish each other’s sentences, echo sentiments, or gently remind one another that each story has two sides.

“We looked after each other,” Adrian says. “Bonjo and me had big arguments, but it was fine. If I felt something was right, I’d fight for my case all day long.”

And as such, there was no question that either Adrian or Bonjo would compromise in the service of an industry that didn’t want to know.

“It was really just experimentation,” Adrian reflects. “But all those times experimenting in that period led to loads of things in the future.”

Three more records followed in quick succession, and by the middle of the 1980s, African Head Charge had established a central place in On-U’s catalogue with an ethos that would go on to define the label.

“I think in life you have to prove yourself by doing good work,” Adrian says. “You can’t get through by bullshitting or paying for something. You have to show you’re worthy of a little bit of respect, and that sometimes takes years to achieve.”

You get the sense that he’s suggesting the time has come for others to recognise the work African Head Charge have put in.

“Back then, what we were doing was so good, I thought we could change the world.”

Fast forward to 2023. While their approach remains the same, circumstances for both musicians have changed. Bonjo now lives in Bolgatanga, a town in the Upper East region of Ghana, not far from the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. At weekends, he heads down to Big Milly’s on the beach in Accra to watch the master drummers of the local Ga tribe, eager to absorb the atmosphere and learn some of their rhythms to integrate into his own playing.

“We used to go and jam with them, even go to their rehearsal place,” Bonjo says, his eyes lighting up. “I’m a grown man, but when you’re learning you become like an eight-year-old. It’s really fun and exciting.”

As well as teaching himself, Bonjo invited many of the Ga and Bolga musicians he met into the studio to record the material that has since formed the basis of ‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’. Among them was King Ayisoba, the king of the kologo (two-stringed lute), who was born in Soe, 15 miles north of Bolgatanga, and who features on two tracks.

“Bonjo was in Ghana, recording King Ayisoba and getting some chants and brilliant playing,” Adrian explains. “We were in Ramsgate, firing files back and forth to Doug Wimbish in America and to Perry Melius in East London.

“It’s like cooking,” says Bonjo. “Putting things together and seeing what it tastes like.”

Maybe it’s because they’re waiting for lunch to arrive, but neither Adrian nor Bonjo can help describe African Head Charge in anything other than culinary terms.

“It’s raw, wholesome, there’s spice and also an element of, ‘Oh my goodness, what’s that?’,” Adrian enthuses, putting high stock in musicians Skip McDonald, Wimbish, Melius and others who have played with African Head Charge over the years. “We’ve been able to pull in some great guests to make this banquet. Their calibre in conjunction with our other ingredients… there’s something about it that I can’t quite put my finger on, but it’s mighty.”

“The thing about it is different people’s contributions,” Bonjo offers. “That’s a part of the spicing too. What I do is completely different from what Adrian does, so putting all these things together, everybody comes together to make one thing. And that’s what it is.”

Nowhere is this more evident than on tracks like ‘Accra Electronica’ and ‘Asalatua’, on which Adrian has run live drums through a Cinema Engineering EQ and laced it with Ga conga rhythms. It has the feel of a traditional Ga fishing song, the repeated “eh-ba” chant calling out the rhythm of the nets being pulled back.

Studio technique is one thing, but as any good chef will tell you, without the right ingredients there’s not a huge amount you can do.

Timing is also key, of course, and perhaps equally important to this new work is the sense that things have come together in a way that feels right for both Adrian and Bonjo. The latter makes no secret of his desire to stay in Ghana and is excited by the possibility of continuing to learn from those around him.

“I really love it there,” he says, his contentment palpable. “My plan is to spend the rest of my time there and maybe do some more recording. Different types of drumming, different tribes. That’s where my heart is. From Jamaica, I come to England and then Africa. Because you know all Rasta men always talk about Africa, and for me it’s not just talk, it’s action. We want to go to Africa, so we’ll go!”

Although the hustle is still there, Adrian is also happy to let the African Head Charge project evolve at its own pace. He is particularly proud that, with the help of Warp, the On-U Sound brand is back to where he thinks it should be.

“At our age, we’re just living our lives,” he says. “When we do a gig we enjoy ourselves, and when we make a record we make sure it’s proper. I don’t feel we’re in competition with anybody.”

“That’s it – we do what we want,” Bonjo responds. “And if you love it, you just love it. It’s got nothing to do with getting any big hits… it’s to create something.”

For all its evident quality, it’s unlikely that ‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’ will sell the 300,000 copies Adrian Sherwood jokes about. But while the bravado of youth may have given way to a more relaxed realism, his belief in the work remains as strong as ever. Does he still think African Head Charge can change the world?

“No, but I think we can make a good record. I don’t feel like I did, but I do feel empowered again and really on it.”

Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah agrees, but he offers a slightly different perspective.

“That thing of changing the world…” he muses. “I’m hoping that through our music it can let everybody know that it doesn’t matter where you’re from or what language you speak, we’re all part of the human family. If we can do that through music, then that is changing the world.”

On the album’s penultimate track, ‘Never Regret A Day’, this message is clear: “Good days give you happiness, bad days give you experience / Worst days give you a lesson and best days give you memories.”

Adrian and Bonjo have had their share over the last 42 years. On ‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’, those ingredients have been distilled into something unusually tasty.

“I’ll stand by all of what we’ve done,” Adrian concludes. “At best, it’s insanely good, and at worst it’s at least ‘interesting’.”

He laughs. The food has arrived and it’s time to eat.

‘A Trip To Bolgatanga’ is out on On-U Sound