In his autobiography, ‘Remain In Love’, Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club founder Chris Frantz recounts a life of being propelled around the world by art and rock ’n’ roll and insists “it wasn’t all conflict”

The man who is responsible for the formation of Talking Heads has no memory of being involved. Chris Frantz, the group’s drummer, is discussing the research process behind his new autobiography, ‘Remain In Love’, when this fact pops up.

“Mark Kehoe, the fellow who introduced me to David Byrne, was making a student film about his girlfriend getting run over by a car,” explains Frantz. “He wanted a little musical piece for his film and I said I would help him with it. David did too. It was the first time I had ever played any sort of music with David, but my friend who arranged the whole thing can’t remember it at all. He can’t even remember the film!”

Frantz, fortunately, is considerably less rusty. His autobiography is astonishing in its detail.

“So much has been written about Talking Heads and it’s always the same old shit,” he says. “It’s always ‘the conflict, the conflict, the conflict’, and the truth is we had the opposite of that most of the time. Yes, there was some disagreement – I mean, who doesn’t have that in their lives? – but on the whole it was really quite a positive experience.”

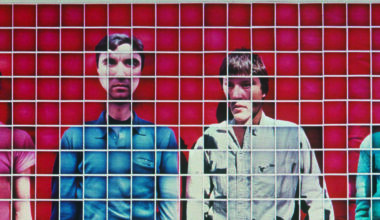

A percussionist first and foremost, Frantz formed Talking Heads with David Byrne while studying at Rhode Island School of Design in Providence in the mid 1970s. A move to New York ensued and eventually Frantz persuaded Tina Weymouth, his wife-to-be, to join on bass. The group was completed by keyboardist/guitarist Jerry Harrison when they signed to Sire and the rest is new wave history.

However, while Byrne’s preternatural talent as a frontman has long drawn focus, Frantz and Weymouth – both key in the writing and decision-making of the group – were often unfairly cast as simply the motor behind the machine. They disproved this logic somewhat with their independent success in Tom Tom Club, but ‘Remain In Love’ further redresses the balance. The book is a great read too.

Chris Frantz’s recollections are vivid. The child of a high-ranking military lawyer, he does not attempt to disguise or play down an upbringing of comfort and privilege. But that context makes some of his later decisions seem pretty brave. Stepping around bodies on the Bowery, for instance, which he writes about in ‘Remain In Love’ when describing his early days in 1970s New York.

“It was a shocker,” says Frantz. “But as difficult as the environment was, I felt we weren’t alone. One block away were Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, two blocks away was Ornette Coleman. The conceptual artist Vito Acconci was just down the street and the Ramones were three blocks away, or at least Joey and Dee Dee were. So there was this artistic community there. The place was a hellhole, but behind closed doors you had all these geniuses.

“I did have my first sleepless nights around that time because I thought, ‘Am I going to be able to survive this? Please, please don’t let me end up like one of those guys on the Bowery’. But we had CBGB’s, which was this oasis in the middle of the whole thing. And it wasn’t just CBGB’s. There were other places in SoHo, places like The Kitchen, where avant-garde performers would play. We saw Jonathan Richman there after he split up The Modern Lovers and went acoustic. He had the drummer pounding the floor with rolled-up newspapers. It was a very interesting time, despite the fact that it was also kind of brutal.”

Frantz’s book is full of these little poetic details. At one point, he recounts a “field trip” to New York from Rhode Island to see John Cage perform ‘Music Of Changes’. The show was followed by a conversation with members of the audience, during which Cage offered each attendee a single wild mushroom and a thimble-sized glass of his favourite wine. This was the same night that Frantz first heard Kraftwerk, on a jukebox at the nearby Spring Street Bar.

“I wasn’t really well-versed in electronic music before then,” he admits. “I knew things like Hot Butter’s ‘Popcorn’ and The Tornados’ ‘Telstar’ and Timmy Thomas’ ‘Why Can’t We Live Together’, but there was some funk in Kraftwerk and I don’t think I’d ever heard a vocoder before, so it was very exciting. They had ‘Autobahn’ on that jukebox and somebody had put in a whole roll of quarters so the song just played over and over and over again!

“We got back to Providence and the next day I went out and bought the ‘Autobahn’ album. It was a revelation and something that we remained interested in for years. A few people have said to me, ‘The first time I heard Kraftwerk was on the PA system at a Talking Heads show before the band went onstage in 1978’.”

‘Remain In Love’ is not light on major celebrity cameos. Frantz spots Mick Jagger alone in The Tin Palace jazz bar in New York’s East Village, high and singing along to Roberta Flack’s ‘Killing Me Softly’, loudly inserting the refrain, “Blowing me softly… with his lips”. He witnesses Lou Reed eat an entire tub of ice cream using his heroin spoon, the only spoon he has in his apartment. He recalls the first time that Talking Heads met Patti Smith, who immediately dismisses them with the line, “I wish my parents were rich enough to have sent me to art school”.

Frantz has a knack for capturing quick but unflinching portraits of the flawed humans behind the curtains of fame. So what has he come to observe about the impact of celebrity on creative personalities?

“I think some people handle it a lot better than others do,” he replies. “Looking back, I realise the pressure that is on somebody like David Byrne, who was in the position of being the lead singer and main lyricist, is probably greater than I was aware of at the time. So I think I’m now more sympathetic about the effect that celebrity has. I realise that sometimes it’s not the best thing for people.”

Given that Frantz and Tina Weymouth have long been such a rock-solid couple, effectively their own support network, it’s notable that Byrne must have frequently felt like a third wheel.

“Yeah, David expressed that more than once to us,” reveals Frantz. “He’d say that he was jealous of our relationship. And that was the exact word he used. We always included David in our activities – if we went to a party, we brought him to the party, if we went to the theatre, we invited him to go with us to the theatre – and we felt protective of him. He was our friend and we wanted him to know that we loved him and we loved working with him. Unfortunately, I’m not sure that message was fully received by him. He is wired differently and I think that he might not have really understood how highly we regarded him.”

A lot of the much-vaunted conflict in Talking Heads seems to have been centred on the writing credits for the group. The ‘Remain In Light’ album, released in 1980, is the classic example. Despite an agreement stating that the whole band and producer Brian Eno would receive credits, the initial pressing of the record heavily favoured Byrne and Eno and did not attribute any of the writing at all to Frantz and Weymouth, although this was corrected on later versions. Did Frantz ever feel that Byrne’s attitude may have been a reaction to the unique dynamic that he and Weymouth had as a couple?

“I think that, in David’s case, he can’t help himself,” he says. “It’s just how he does things. If you want to do a project with David Byrne, you’d better be prepared for him to think that it’s his project. There’s plenty of collaboration during the process, but then he’ll say, ‘Oh, what a great song I’ve written’. I always called him on it. I always said, ‘But, David…’, but he doesn’t know where he ends and other people begin. He’s brilliant – and we continued to work with him because of that brilliance. We wanted to keep it going because the band was so different and so unique compared to basically everything else that was going on.”

In this context, and with David Byrne increasingly focusing on solo work, it’s easy to understand how the prospect of Tom Tom Club became so appealing. The contrast of Frantz and Weymouth’s experiences in Talking Heads against their harmonious married life must have felt stark. Indeed, for all his creative victories and the compromising opportunities of stardom, it’s the success of his relationship with Weymouth that is the real achievement of Frantz’s adult life. Hence the title of his book.

“My love for Tina remains very strong to this day,” he says. “I consider myself extremely fortunate that I ever met her. But not only did I meet her, I was able to work in a band with her and still have the husband and wife experience. We don’t always agree, we have independent thoughts, but we also make a good team.”

The thing about being a couple within a wider group – whether that’s a band or a house share or something else – is that, as a unit, you can get used to laying the fault conveniently at the door of others. Removing that crutch can sometimes result in a sharp learning curve for a relationship, both in terms of work and personal life.

“In Talking Heads, we had responsibilities very clearly divided between us,” acknowledges Frantz. “So the first day of recording as Tom Tom Club, without David and Jerry in the room, I was really kind of unnerved. I drank too much and I was unable to function properly. I basically ruined the first day because of that. But by the second day, I got myself together.”

The line-up of Tom Tom Club later included Adrian Belew, recruited to add “some magnificent guitar”, but he wasn’t present for the initial sessions. Island Records owner Chris Blackwell was judging the viability of the project on the first single, so the pressure was on.

“We recorded ‘Wordy Rappinghood’ and fortunately Chris liked it very much,” says Frantz. “Tina struggled with it for a little while to begin with. She was thinking, ‘What is this song going to be about? What should I write about?’. And then she thought, ‘Words! I’ll write about words!’. And that was a brilliant idea. Working without David and Jerry was a bit of an eye-opener, but on the other hand it was liberating. We realised, ‘We can do this, we can do something cool that will be completely different from Talking Heads’.”

Ultimately, just as Talking Heads’ angular funk had made them ideal foils to touring partners like the Ramones, Tom Tom Club’s playful tone set them worlds apart from their po-faced post-punk peers. What’s remarkable is they were in that headspace at all. Many people in Frantz and Weymouth’s situation would have gone into the project with chips on their shoulders and subsequently produced something harder and heavier. Instead, in an almost off-the-cuff fashion, the pair proved exactly how much colour they brought to Talking Heads. Weymouth put it best, once telling the LA Times, “We have to be Dada. To us, you can’t offer just anger – it will eat you up from the inside. You’ve got to have a sense of humour”.

“Yes, we were conscious of that,” agrees Frantz. “We wanted the tone of Tom Tom Club, or at least the first album, to be the sort of record that our friends would put on at a party and everybody would get up and dance to it. We wanted to create a good-time record that also had a little bit of a bite to it – but not too serious a bite.”

It’s been quite a while since the last Tom Tom Club album, but Frantz and Weymouth retain their interest in the project. Frantz believes they may even gig again at some point in the future.

“Nobody is breaking down anybody’s door for a rock ’n’ roll tour right now,” he notes. “But it’s very possible. We have also thought that we’ll do an electronic album with the type of sound that inspired us when we first heard Kraftwerk. We could do a record of just Tina and myself with some synthesisers and a drum machine, which would be something new for us. That kind of appeal, to be underground, to be avant-garde, would be really nice at this particular stage in our lives. Tina is working on her own book too, which will be amazing I’m sure, and I’m thinking about a second book. It won’t be a rock ’n’ roll memoir, it’ll be some other type of thing.”

Get the print magazine bundled with limited edition, exclusive vinyl releases

If you’ve heard the one-off track that Frantz and Weymouth recorded under the name Chris Und Tina in 2017, which was released on an Electronic Sound seven-inch, you’ll be thrilled at the possibility of a whole album of electronics from the couple. There’s also, of course, the eternal question about the prospect of a Talking Heads reunion.

“Well, I’ve kind of given up on that,” says Frantz. “I’d be very pleasantly surprised if David gave us a call. I would love that, but I just don’t see it happening. It’s been so long and he’s so happy with his show. It’s like, ‘OK, you don’t want to go backwards, but you’re playing Talking Heads songs’. So, you know, stop making sense… please!”

Speaking of making sense of things, has a period of retrospection changed the way Frantz thinks about himself? Are there points in his life he wishes that, like his friend Mark Kehoe, he couldn’t recall?

“Certain days were very intense,” he admits. “Remembering things that were probably not the best days in my life, that was difficult. I got myself the book deal and sat down to write… and I was totally overwhelmed. I had this enormous anxiety attack, which is not something I usually experience. On the whole, though, I really enjoyed it, because I wanted the tone of the book to be positive and I wanted to remember the wonderful times we had. I mean, to be in England with the advent of punk rock was terribly exciting.

“Looking back, I’m proud of myself for having weathered that whole thing and also realising that, in fact, I was an important part of what was happening with Talking Heads, as was everybody else in the band. As Dee Dee Ramone said, ‘I’d like to give myself a big pat on the back’.”

‘Remain In Love’ is published by White Rabbit