“So we found out about CBGB’s and we found out about Patti Smith and The Ramones and Television, and we knew that there was something going on” – Chris Frantz

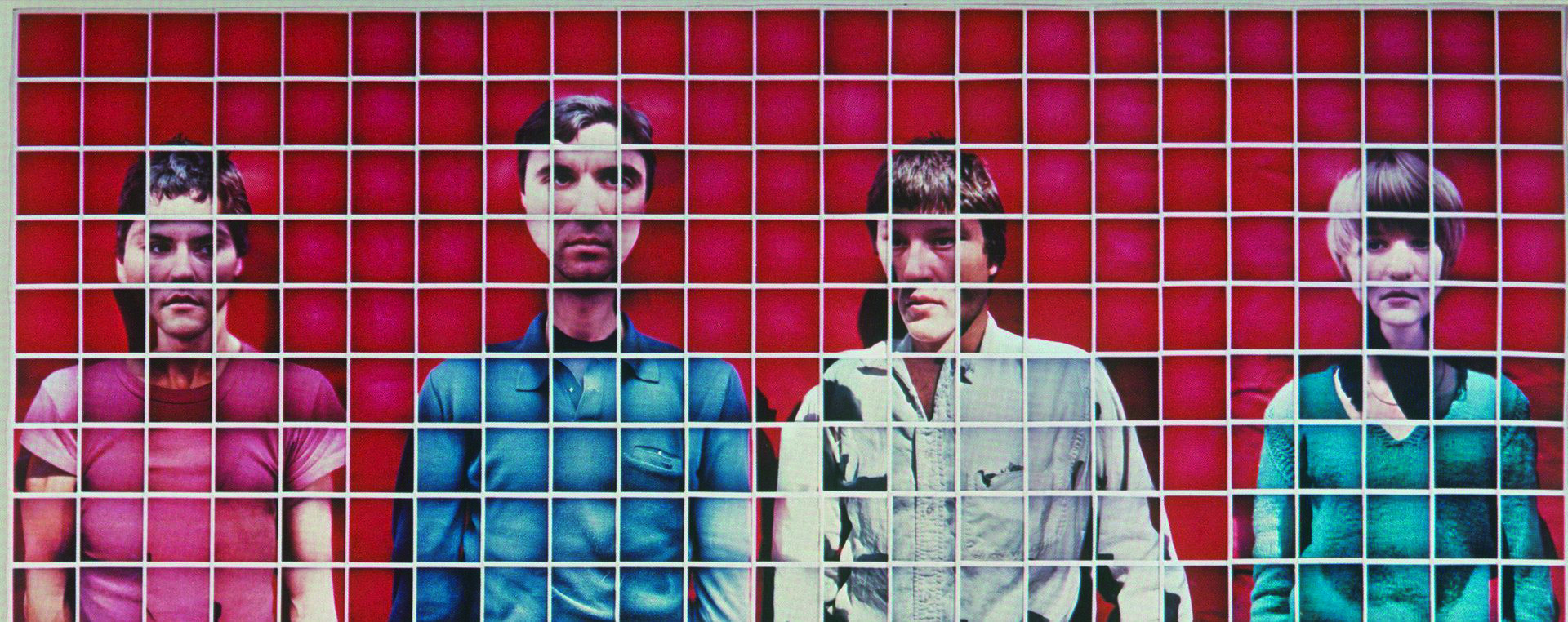

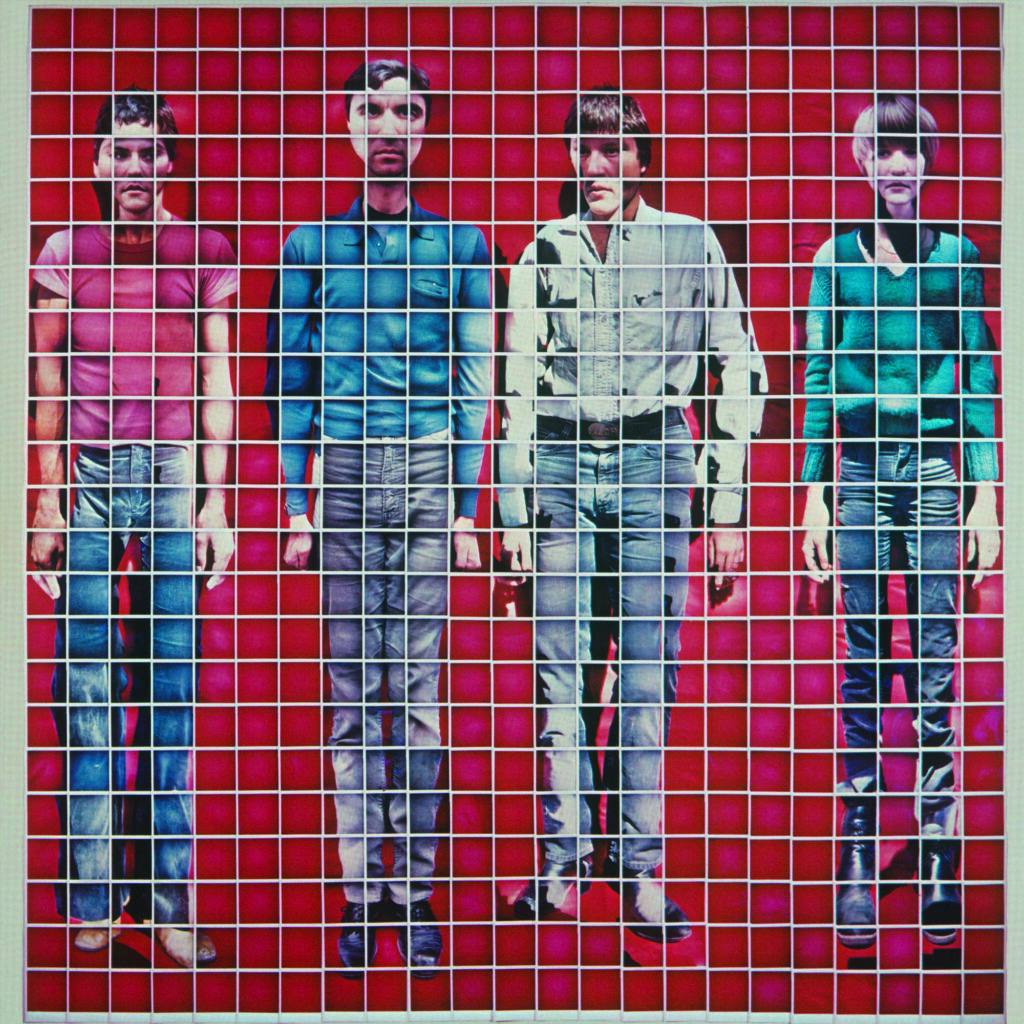

Talking Heads ‘More Songs About Buildings And Food’

In the summer of 1978, New York was hot, dirty, dangerous, and the most exciting place on Earth.

In London, the English iteration of punk rock – that brief, savage earthquake – had effectively been over for the better part of a year; living on in aftershocks, in cosplay from those who hadn’t grasped the point, and in the ground it cleared for new ideas from those who had. But five hours west, the scene that had grown up in downtown Manhattan, where its Bowery heartland was still skid row central, was blossoming. And Talking Heads were in the middle of it.

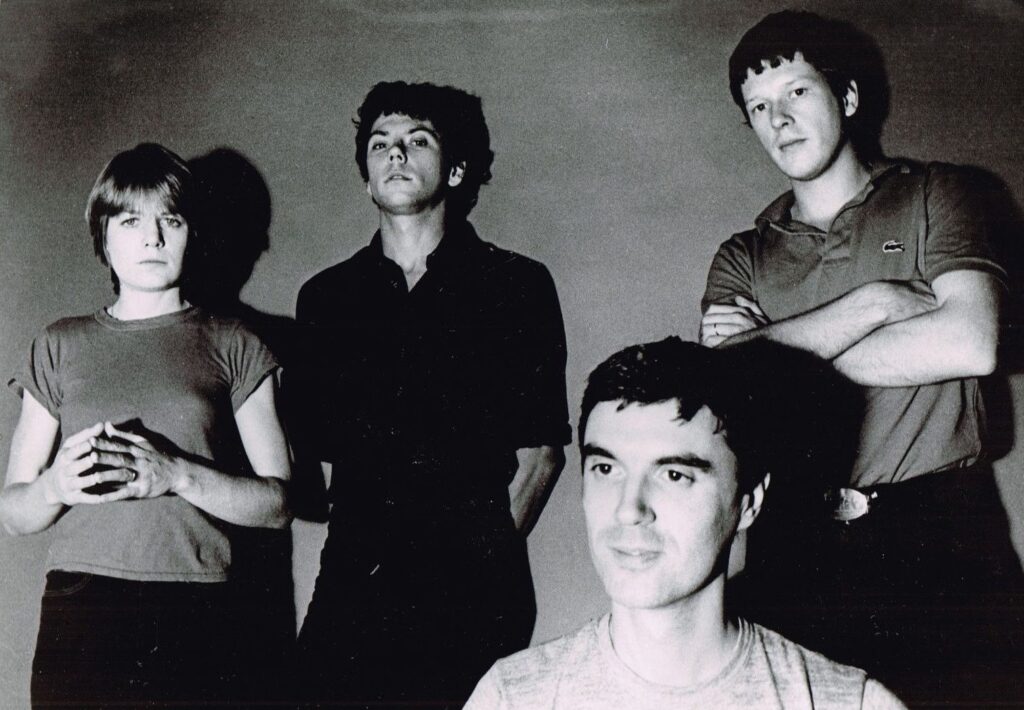

It was three years since a trio of alumni from the Rhode Island School of Design – David Byrne, Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz – had moved there and changed the name of Byrne and Frantz’s band. Once they enlisted Weymouth, they no longer called themselves The Artistics. The name of this band was Talking Heads.

It was two years since they had started playing what was all but a residency at CBGB’s, and thereafter got themselves signed to Sire Records. It was a year since they had recruited a fourth member – guitarist and keyboard player Jerry Harrison, formerly of The Modern Lovers – and recorded their debut album, ‘Talking Heads: ’77’. And also a year since their rhythm section, bassist Weymouth and drummer Frantz, had married each other. And it is exactly 41 years later – on his wedding anniversary – that Chris Frantz answers the phone to me with a cheery “He-llo!”, and in response to my polite enquiry as to how he is, replies that he is “Super cool!”.

Well, I could have told him that.

With the exception only of David Bowie, no musical act has been as constant in my affections, as continuous and welcome a presence in my life and in my ears from the moment I first heard them, as Talking Heads. The reason for it is the astonishing run of albums that began in the summer of 1978 with their second LP, the exhilarating and inventive ‘More Songs About Buildings And Food’. They took yet another leap with the following year’s angular, mysterious ‘Fear Of Music’, before then recording the peerless masterwork that is 1980’s ‘Remain In Light’, in whose dense, spooky, whitewashed Afro-funk I find something new and thrilling with each play.

Things moved quickly in those days. From Chris Frantz’s arrival in New York to his band producing their fourth album took only five years. In 1975, he’d gone to live in a city he had visited only twice before.

“We knew that New York was the place to be,” says Chris. “We knew that Andy Warhol was there, Lou Reed was there, the art scene in Soho was burgeoning… We knew it was the right place for us.

“I had a summer job painting a mural in a hospital in Pittsburgh and I’d saved up enough money to make a deposit on a loft. We spent the first six weeks living with Tina’s brother, Yann Weymouth, who advised me I should look in the industrial section of the New York Times. A lot of the available lofts were in really, really bad condition. But I found one that was only in moderately bad condition, and it was three blocks away from CBGB’s. It had a beautiful view of the Empire State Building from uptown. It was a building that was all industrial except for us, so there were no neighbours at night to complain about a band playing too loud. It was a place where we could work on our music and write songs and rehearse and get ready to make an appearance in public.”

It’s a common factor in cities that produce great pop culture movements that the young and impecunious can find a way to live and create there. London and New York shared this now extinct attribute in the 1970s and 1980s. I’d suggest it’s no coincidence that, Britpop and the 2000s NYC rock scene notwithstanding, neither has been the setting for anything comparable since.

“I had insomnia for several weeks,” continues Chris, “because everything was so stimulating and, I guess you could say, scary. I was thinking [and here he segues, perhaps unwittingly, perhaps not, into what sounds like an almost perfect Talking Heads lyric] about the subways under the ground, the traffic on the street, airplanes in the sky overhead, and lots of challenges. I was not a big-city person.

“The first day I moved to New York, I went to visit another RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] guy, who lived at 52 Bond Street, which was catty-corner across the Bowery from CBGB’s. He said, ‘Chris, I know you’re interested in music, there’s something going on at this place across the street’. So we found out about CBGB’s and we found out about Patti Smith and the Ramones and Television, and we knew that there was something going on.

“What I had hoped to find was a place kind of like the Cavern Club was to The Beatles. Or the Star-Club in Hamburg. An incubator where you’d be able to perform without too much of a critical audience and hone your craft and get good. CBGB’s was just like that. And it was a real scene. Not just other musicians, but artists of all types, and also a smattering of prostitutes and dominatrixes. It started off as a very small scene. Like the first time we played, I think there was maybe 15 or 20 people in the audience. And we were opening for the Ramones. Most of the audience was either our friends or the Ramones’ girlfriends. It gradually grew to the point where there were lines around the block and, you know, lots of excitement. From when we first played, I would say that took about a year.”

When I think of the Liverpool scene that produced The Beatles, the British punk and post-punk scenes, and the New York of the mid- to-late-1970s, I think of a melding of art school and street cultures. When I ask Chris if he was conscious of this at the time, it sounds as if he has abruptly succumbed to a terrible coughing fit. After a moment, during which I fear my question has literally made him choke, I realise a dog is barking next to his telephone.

“Aside from Patti Smith, we were like the art students there,” says Chris, blithely ignoring the dog. “Patti Smith complained to me the first time I met her, ‘Oh, I wish my parents had the money to send me to art school’. You know, most of the people playing at CBGB’s were not former art students. They were kids who were copying The Rolling Stones or The Who. There were some great bands, but there were also a lot of really not-that-interesting bands who wore platform boots and spandex. People who idolised the New York Dolls and hadn’t quite caught up.”

He ponders how to phrase this kindly.

“They didn’t have exactly a unique perspective,” he offers.

Which makes me wonder, what else about that golden moment in New York has been mythologised? What are the biggest differences between the way people talk about it now and how Chris experienced it at the time?

“Well… hm, that’s a good question. To be honest, it was both very romantic and also very intellectually stimulating, so I don’t think people exaggerate how great it was. People may exaggerate how great certain bands were, but then again… What was happening in America at that time was arena rock – The Eagles, Boston, Elton John, Debby Boone, The Carpenters – and we thought, ‘Well, if we play our cards right, we can be just as popular as these people!’. So, I’m not a big fan of The Eagles and we were definitely not big fans of Elton John at the time, but they were out there doing it. They were writing songs, touring, working their asses off. So we thought, ‘If we want to go down in musical history, this is what we have to do too’.”

And by the summer of 1978, that’s exactly what Talking Heads were doing.

“We had just recorded ‘More Songs About Buildings And Food’ in the spring and we were touring very heavily. We were working hard to establish our reputation. But we were basically working against a punk backlash.

Not that we were punk, but we played the same venues as the punk bands and we often shared the stage with people such as the Ramones.

“It wasn’t such a problem in England, but in America there were FM radio stations that would say, ‘Oh we don’t play the punk music, we only play good music’. They would only play our record if we came to town. Fortunately for us, Seymour Stein, our record company president, came up with the idea that, ‘Oh, Talking Heads, they’re not punk, they’re new wave’. Then the radio programmers would say to themselves, ‘Oh! They’re new wave. Well, we can play new wave’.”

Does Chris think there was a big shift between recording ‘Talking Heads: 77’ and ‘More Songs About Buildings And Food’, the album that broke things open for Talking Heads?

“Yes,” he replies emphatically. “I’m very happy with the results of the first album, but it wasn’t nearly as much fun as the second one. The second album, of course, was produced by Brian Eno, along with the band, and we did it in the Bahamas. We really sailed through the recording because we were so well prepared. The results speak for themselves – really good songs and really interesting production.”

At the time, were you conscious of a shift towards funk and dance rhythms? Did it feel like a natural way forward for you?

“Yes,” he says even more emphatically. “We were big fans of funk music and rhythm and blues and even disco, that was the type of music we generally played when we were at home, just for our enjoyment. I guess we got funkier and funkier. I know when we recorded ‘Take Me To The River’ we thought, ‘Wow, we’re really doing it now – we’re really getting funky!’. In retrospect, it’s not that funky, but it is very strong, in a different kind of offbeat way.”

For you as a drummer, was that particularly satisfying?

“It was. I felt that funk, rhythm and blues, reggae and dub music were ways that we could elevate our musical discourse.”

You mentioned Brian Eno coming on board as your producer. That was shortly after he’d finished working on Devo’s first album. Was that part of what interested you in him?

“We actually spoke with him about doing it before he worked with Devo. We met Brian the first time we ever played in London, which was at The Rock Garden in Covent Garden. He came to see us play, and afterwards we had lunch with him, and visited his apartment in Maida Vale. We had a really good rapport with him and we were very keen on having him produce our album. But this was before I think he had even agreed to do Devo’s album.”

Back then, did you feel a sense of being part of something bigger than the group itself?

“Yes, indeed. In those days, the downtown scene in New York, the art scene, was exceptionally vibrant and lively. Not just music, but painting and video and performance art. It was a great time to be in New York.”

And was there ever a point at which you stood back and looked at what you were doing, and other bands such as Devo and Blondie, and thought, “Yeah, we’re killing it here”? Chris pauses over his words.

“Well, it was always a struggle,” he says with a chuckle. “When you go out on tour, it’s kind of like being in a war. You can get wounded, or you can have a great victory, or you can have a Pyrrhic victory. It’s very challenging. Personally I loved it. I’m working on a book right now, and when I look back on our schedule I think, ‘How the hell did I do it?’. But somehow we did do it. And you know, everybody in Talking Heads had a very strong work ethic. We were determined to succeed. And we were also determined to always try to set the bar higher than people might expect it to be.”

Was it tougher for some of you than others?

“I think it was harder for Tina. Just physically harder. But she did great; she did great always. You know,” Chris sighs and hesitates. “I would like to regain control of the narrative that there was always extra pressure on Tina. The press, particularly the British press, always made much ado about dissension and disagreements and so on that happened in Talking Heads when it really wasn’t such a big deal. I’m not saying that it wasn’t hard for Tina and I’m not saying that David didn’t treat, in fact, all of us rather badly. It’s just that we never had the big fights. We were all on the same page. We were happy to be doing what we were doing.”

And looking back now, is Chris satisfied with the results?

“Yes,” he says, very emphatically indeed, and I can almost hear him grinning down the phone, before he actually starts laughing.

‘More Songs About Buildings And Food’ was released by Sire in July 1978