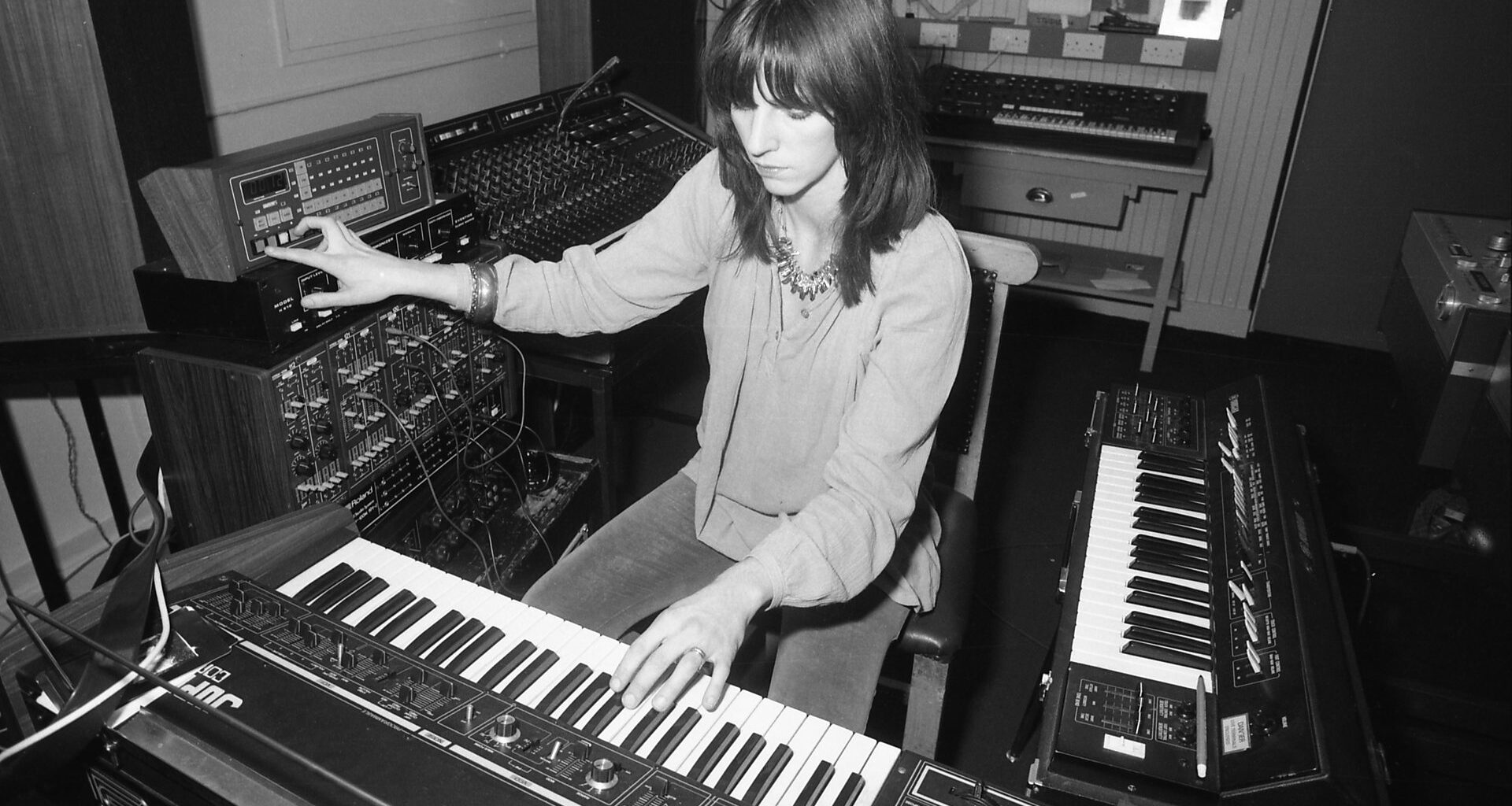

Elizabeth Parker was a BBC Radiophonic Workshop mainstay and one of Britain’s most in-demand composers of TV and film soundtracks. A new compilation, ‘Future Perfect’, gathers together previously unheard pieces from her own private archive. Expect ghostly nuns and clunky scaffolding

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here