Big-name DJ, go-to producer, award-winning soundtrack artist… David Holmes needs no introduction. And his first solo album for 15 years – the blistering, euphoric and exquisitely crafted ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’ – is an absolute pearler

David Holmes is an avid note taker. Whenever he hears an expression, phrase or sentence that resonates, he writes it down. It can come from anywhere – a magazine article, the radio, a TV show, snatches of conversation caught when he’s out and about. The words don’t have to mean anything at first, they just have to strike a chord.

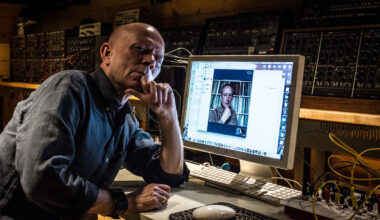

“You write it down for a reason,” explains the genial 54-year-old producer, composer and DJ from his studio bunker in his native Belfast. “You don’t know what that reason is, but you write it down because it speaks to you in some way. And then once you’ve got thousands of those you can go back in and start playing with them. Then you start to form sentences, and before you know it you’ve written two verses and a chorus. And then you go, ‘Ah, that’s what I’m writing about’.”

These stumbled-upon words and overheard turns of phrase lie at the heart of Holmes’ magnificent new album – his fifth, and his first in 15 years – ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’. A stunning combination of emotive electronic body music – “I knew I wanted to make an album that had more energy, but I didn’t know what it was about, so I never got round to doing it” – and a scabrous broadside against many of the world’s current manifold ills, this righteous rebel-music has been warmly received across the musical spectrum for providing a dose of the good medicine many of us need right now.

“People have really embraced it,” he beams infectiously. “Which is really all that you can hope for in this day and age. I’m actually surprised people can afford to buy records, they’re so bloody expensive. And the whole world is in such a horrible place. But it feels like people have responded to it, which is great. It makes it all worthwhile. As much as we say, ‘We don’t care’, it’s good when you touch a nerve.”

Since Brexit, Holmes’ note taking has bordered on the voracious. One of the closing tracks on ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’, a wonderfully evocative piece of krautrock-meets-electronic dreampop titled ‘Tyranny Of The Talentless’, was named after he heard someone use the phrase on the radio.

“I think it was the James O’Brien show,” he recalls. “They were discussing the downfall of the British government, and I thought, ‘I’m having that’.”

Holmes says he’s always been conceptual, and while he doesn’t set out to make conceptual albums, he readily admits that he likes to tell a story. His first two albums, 1995’s ‘This Film’s Crap Let’s Slash The Seats’ and its follow-up two years later, ‘Let’s Get Killed’, have often been described as soundtracks to imaginary films, such was the vogue at the time. In 1998, he began a fruitful creative relationship with director Steven Soderbergh, scoring the acclaimed soundtrack for ‘Out Of Sight’ and going on to work on the filmmaker’s ‘Ocean’s’ trilogy.

“I like seeing a narrative and watching it form. Sometimes you don’t know what that narrative is until you’re into it – like this album. ‘The Holy Pictures’ [an atmospheric meditation upon his parents’ deaths] was the same. The lyrics on this record are all the stuff I’d written down, and then I took it and shaped it into a song.”

Holmes’ ongoing battle with his own mental health is another bedrock of the album. He’s naturally obsessive – “75 per cent of my obsession is brilliant, but the other 25 can be really destructive… you go to some really dark places” – and during the pandemic faced his demons head-on. Alongside the “psychedelic therapy” of imbibing magic mushrooms, the natural pause of the lockdowns allowed him to reset.

“After addressing that, it really was like a reawakening,” he says. “There was a calmness with it as well. I was always quite an intense person, and having cleared that fog I was able to take a breath. The rest of the album is about what I saw when I got through that.”

Holmes’ candid approach to his struggles has won him plenty of admirers. He’s received lots of messages from fellow sufferers – particularly men – thanking him for speaking up with honesty and authenticity.

“For whatever reason, men don’t feel comfortable talking about it. But actually, the minute you start talking you realise that everybody is suffering from it. And I’m really enjoying that because I know I’m helping people. That’s the best feeling in the world.”

As the fog was lifting and Holmes began to “pay attention to where I was getting my news from”, he started working on the soundtrack to ‘This England’, Michael Winterbottom’s coruscating account of the government’s (and specifically Boris Johnson’s) handling of the early days of the Covid crisis. It was more fuel to his fire.

“‘This England’ was a bit too soon for a lot of people,” he muses. “I think it’s a great piece and I loved being part of it, but I was working on that during the second wave of Covid, so it was still very much happening. It made me really angry, but my mind was clear to get angry.”

What follows is a quick-fire verbal fusillade of excoriating establishment take-downs. Michelle Mone and her £10 million yacht, the vast sums spent on the Test and Trace debacle and the dodgy PPE contracts – they all get short shrift from Holmes, but his most righteous invective is saved for those occupying the highest seats of power.

“Anyone who goes to Eton should not be allowed anywhere near Downing Street because they don’t have any empathy,” he sighs. “They’ve been in boarding school since they were eight. The whole trajectory of their education is based on never standing down, never giving in, never admitting that you’re wrong. And on top of that you’ve got this privilege and entitlement.”

He pauses for a second, takes a breath, and then continues…

“When you look at Boris Johnson’s life as a human being, I mean, it’s obvious that he didn’t become a politician to help people. Boris Johnson didn’t give a flying fuck about the rest of his cabinet, never mind us.

So why did he get into politics? He probably knew enough to know that if he got into power he could do whatever the fuck he wanted.

“And I think there’s an element of that in a lot of them. I’m not saying they’re all like that. But it’s kind of extraordinary, once they are exposed to crazy levels of corruption… honestly, you couldn’t make it up. At least Dick Turpin wore a mask, as they say. So all that stuff really got into my brain.”

Unsurprisingly, ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’ is a protest album and, unlike some artists, Holmes has no issue with it being described as such. However, what it isn’t is hectoring, belligerent or unilateral. It’s an album couched in passion, heart and a collective zeal – indeed, one of its working titles was ‘Only Love Can Save Us’. This compassion is evident in the music. While the lyrics often deal in existential dread (granted, the lyrical roll call of iconoclasts that comprise ‘Necessary Genius’ such as Terry Hall, Angela Davis, Tony Wilson and Nina Simone is suitably inspiring), the sounds are joyous. This was no accident.

“If you listen to a lot of protest albums from the 60s and 70s, listen to ‘What’s Going On’ by Marvin Gaye – if you’re not really deep into the lyrics it’s actually a really warm positive record. So ‘Blind’ takes these sometimes really negative issues and puts a real heart behind them. It’s like soul music. They’re singing about heartbreak and devastation, but there are these big symphonies that make you feel great.”

In any case, Holmes says he doesn’t have the stomach to be permanently angry – “That would drive me a bit insane” – but he does think it’s “OK to feel good about protesting”.

“It’s more about waking up,” he explains. “It’s more of a call to arms, metaphorically speaking. Paying attention. Being aware. There is light at the end of the tunnel, because if we didn’t have hope we’d be in a pretty bad place. It would be a never-ending spiral of doom. And I wasn’t in that place. I was more about ‘we’re all in this together’. We’re also all alone in this together. So, it’s about focusing on yourself, but also acknowledging the ‘we’ rather than the ‘me’.”

Two musical luminaries who are also namechecked in ‘Necessary Genius’ loom large over ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’ – Andrew Weatherall and Sinéad O’Connor. Weatherall and Holmes go way back. On a visit over to England to see Weatherall DJ in 1990, Holmes persuaded the ever-shifting musical stalwart to come and play his club Sugar Sweet in Belfast. Weatherall also provided Holmes with one of his most enduring productions – his remix of The Sabres Of Paradise’s ‘Smokebelch II’ in 1993. Their friendship remained strong until Weatherall’s untimely passing.

“I’d say he’s pretty present,” says Holmes. “And the reason why he’s pretty present is I think music was just something Andrew did. DJing was just something he did. He did it incredibly well. He was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, DJ I ever heard – for my tastes and for how he concocted his sets, and for his trajectory as a producer. But that’s just something he did.

“Andrew was much bigger than that. He was a very inspiring man in other ways that have nothing to do with music. His generosity of spirit, that’s something I’ve tried to learn. To look after the young ones, help them out, give them advice, do some work for fuck-all to help people.”

O’Connor, he admits, was a “different animal”. Before her death, Holmes had worked with the embattled singer on a new album, ‘No Veteran Dies Alone’. The album will be released this year, and while Holmes isn’t talking about the music out of respect for O’Connor’s family, he happily describes the experience as something he’ll never forget.

“I feel really blessed,” he smiles. “It felt like I was recording Nina Simone or someone like that. I mean, there are stars – people who are amazing – and then there’s that other tier: Nina Simone, Sly Stone, John Lennon, Sinéad O’Connor, Kurt Cobain, Bob Dylan… she’s in that echelon, but just so brilliantly down to earth and funny. I’ve got a lot of really good memories.”

As for her mention in ‘Necessary Genius’, O’Connor approved. Holmes sent her a message with the song and lyrics written out in full. She replied with “a wee smiley face” and then asked how his daughter was.

“Sinéad taught me not to be afraid to speak up when there’s stuff going down that I don’t agree with. Like what’s happening at the minute. Like what happened during Covid. I think it’s important for me to be on the right side of history and not worry about superficial luxuries like being a DJ or whatever.”

The final component of ‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’ comes in the form of the singer – and Holmes’ goddaughter – Raven Violet. ‘Blind’ might be touted as a David Holmes solo album, but it’s not really. The collaboration between Holmes and Violet (the daughter of Holmes’ Unloved bandmates Jade Vincent and Keefus Ciancia) is pivotal to the record. In Holmes’ vaults there’s a version of the album with him singing all the songs. But after the pair collaborated on the single ‘Love Is A Mystery’ for Golden Lion Sounds, he got her in to sing on the tracks ‘Hope Is The Last Thing To Die’ and ‘It’s Over, If We Run Out Of Love’.

“These lyrics just sounded more powerful coming out of the mouth of this 20-something, young, fierce, intelligent woman, who’s just nonchalant,” he explains. “She became a real influence on me. I hate the word muse, but she was really inspiring to work with because it felt like when I was writing, I could always go straight to the Raven voice in my head.”

Although his musical career has taken him all over the world, and granted him friendships and working relationships with A-list stars, the likes of which the teenage Holmes growing up in a Belfast ripped apart by the Troubles could never countenance, he knows how fortunate he is. There’s a story Holmes is fond of recounting that demonstrates his musical obsession.

One evening in 1990, after promoting one of his early Belfast Art College acid house nights, he found himself back in his bedroom at his parents’ house listening to Ennio Morricone’s soundtrack to ‘Once Upon A Time In America’ and, fittingly, Sinéad O’Connor, when suddenly he began crying.

“I wasn’t sad,” he reflects. “You know that old-school ‘overcome with emotion’? I was just thinking, I can’t imagine not doing this. I mean, it can’t get any better than this. It almost sent me into a panic. But I’ve always had that panic – it’s a real working-class thing – the idea that you could lose everything, and that’s definitely done me good over the years. That’s why I still live in Belfast, because the most important thing, apart from my family and my close friends, is being in my studio in my own home and making stuff.”

Such an attitude means that 30-odd years into his peripatetic sonic journey, David Holmes can honestly say that now is as good as it gets.

“I mean, I’m not happy about the world,” he laments, before perking up again. “But I’m happy. Experience is a wonderful thing. I was always just deeply curious, you know, always wanted to do the impossible, and I had the brass neck to give it a go.

“I’m still going to school. Every day I’m still learning new stuff. I think the most encouraging thing is that I want to learn. What I know is nothing. I still have that mindset. And so I kind of feel that I’ve reached a point in my life where on the one hand I’m really happy, but on the other I feel like I’m only really getting going.”

‘Blind On A Galloping Horse’ is out on Heavenly