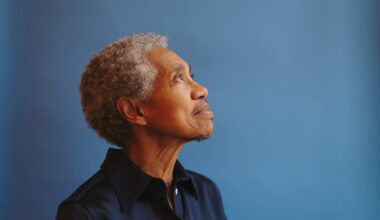

He’s one of the funniest men on telly. He’s also an extremely talented musician. And with the woozy synthscapes of ‘Music For Insomniacs’, he’s paying homage to his big hero, Jean Michel Jarre.

Meet Matt Berry

The first thing you see in Matt Berry’s flat, in the hallway by the door, is a Minimoog leaning up against the wall next to table with an old-fashioned telephone on it. On top of the telephone is a serial killer’s clown mask and beside the table is a pair of cowboy boots. You walk past them to get to the front room. On the sofa, a Roland CR-68 drum machine sits on a cushion.

“Look at that,” says Berry, pointing at the Roland. “I don’t think it’s ever been used. It’s mint!”

Sure enough, the wooden box is pristine and there is no evidence that anyone has been jabbing at its pretty little buttons with greasy studio fingers. The fascia panel looks as clean as the day it came out of the factory. We stand and admire it for a while, then Matt checks himself.

“I didn’t put it on the cushion on purpose. It’s not its special place. It just arrived today and I opened the package on the sofa. Mind you, it does look rather good there…”

I’ve come to speak to Matt Berry because of his new album, a synth project called ‘Music For Insomniacs’. Of course, he’s best known for his television work. He’s created a series of unforgettable characters for some of the best British TV comedies of recent years, including Douglas Reynholm, the mercurial boss of Reynholm Industries on Grahame Linehan’s ‘The IT Crowd’, and Beef, the superannuated 70s lothario neighbour of Vic and Bob in ‘House Of Fools’. There’s also the jobbing voiceover artist and actor Stephen Toast, his most fully realised character yet, in the BAFTA-nominated sitcom ‘Toast’, which Berry co-wrote with Arthur Matthews (‘Father Ted’ and ‘Big Train’).

Alongside this pretty stellar comedy CV, Matt Berry has a successful recording career. He’s signed to Acid Jazz Records and has two critically lauded albums to his name already, ‘Witchhazel’ and ‘Kill The Wolf’. The latter is a particularly skillful blending of the influence of the soundtrack to ‘The Wicker Man’ and films of a similarly unsettling ilk with modern sensibilities that are entirely his own. He’s busy working on the score for the second series of ‘Toast’ when I arrive at his flat.

“The songs are going to be more dramatic, characters will talk to each other in song, like in a musical, and then it will go off into… other areas,” he explains.

The slightly insane nature of musical theatre is something that Berry genuinely likes. Nestled in his record collection (he calls the 100 or so vinyls standing up against his hi-fi unit “the essentials” and says there are many more squirrelled away elsewhere) is a copy of ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’, signed by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Berry presented a segment of ‘The Culture Show’ devoted to the 40th anniversary of the rock opera a few years ago. There’s no doubt that the 1970s left a big impression on the young Berry (he was born in 1974) and his creative life seems largely defined by a few years, somewhere between 1970 (‘Jesus Christ Superstar’) and 1976 (when Jean Michel Jarre’s ‘Oxygene’ was released), a time when pastoral folky prog rock was the leftfield hipster’s choice of listening material and when, sartorially, the cowboy boot and the waistcoat ruled supreme.

The ‘Music For Insomniacs’ album wears some of these influences on its sleeve – literally. The back of the handsomely appointed vinyl edition features a picture of Berry surrounded by his synths, a direct homage to the back cover of Jean Michel Jarre’s ‘Oxygene’ (the first pressing, French, natch). Berry has a stack of Jarre memorabilia; there’s a programme from a concert to hand and he has every edition of ‘Oxygene’ ever released by the looks of it.

Berry’s new album is also something of a tribute to Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’. He says he had the Oldfield album “from a very early age”. It was, I suggest, pretty much issued along with every British passport at one point. Everyone, but everyone, had a copy of ‘Tubular Bells’, didn’t they?

“If your parents were into a certain sort of music, then you might have had it, but my parents and a lot of my mates’ parents weren’t,” says Berry. “The one we all had was Jeff Wayne’s ‘War Of The Worlds’. By the late 80s and early 90s, the mums and dads would have got rid of that record, because it would have been too much associated with the 70s, it would have seemed really old fashioned. I heard it when I was about 10 or 12. I didn’t know about fashion, but I picked up on the chaos and the mental illness of it. It wasn’t like anything on Radio 1 and there was no easy way to listen to it. That was what got to me.”

If you throw in the famous Jean Michel Jarre live shows in London’s Docklands in 1988, which the teenage Matt Berry attended, you have the conditions that birthed this unusual musical talent. He started making music, as so many before and since, at home, working with rudimentary gear.

“When I started recording, I had an organ and a four-track. The organ was £30, a grandad’s organ. I thought it was brilliant. I would put the organ pre-sets through guitar effects pedals, get it sounding a bit like Jarre, and then you’ve instantly got something very cool. That was all I needed. Then as soon as I found out how to record things on top of other things, I was off.”

When did the synthesiser enter your life?

“It came from this,” he says, pulling out a Jean Michel Jarre book stuffed with pictures of the French maestro and his gear. It’s pure synth porn. “This is important. It was the first gig I went to see, over there…” he nods out of the window, towards Docklands. “I was already interested in Jarre by then. When my mum and dad got me this book, I saw that picture, and I decided that was what I was going to have. Around that time, in the late 80s, the gear was cheap, so I got a CS-60…” He points it out on the back of the sleeve of ‘Music For Insomniacs’. “I think I paid something like £200 for it and it was much the same with all these…” He points out the synths one by one. “That there was £150, £50 for that, that’s David Arnold’s… He isn’t getting it back. This here is a white faced ARP Odyssey which I got really cheap. People thought they looked awful.”

I mention that I had the black and gold painted ARP Odyssey, the Mark II, but I sold it for an absolute pittance.

“Oh my God, you should have kept it.”

He’s not telling me something I don’t already know. I miss it dearly and I regularly curse my younger self for letting it go.

“That’s the one Korg are remaking,” he enthuses. “The Korg Mini sold shitloads and they gave me one of those, thank God. I said I’d take it on tour. They said, ‘Would you have any use for this?’ and I said, ‘Yeah! Of course!’, so they sent me one. It went so well, they decided to do the ARP next – full size and everything. They’re working with the old guy from ARP. The guy who took over from Alan Pearlman. It’s going to be brilliant. It’s what people want. We don’t need to have studios full of heavy museum pieces. They have the technology now and they can make them sound authentic. There’s no excuse really.

“Korg are very good. They’ve taken over Vox as well. I was having a word with a Korg rep recently and I think they’re thinking of doing a combination organ like the Vox Continental, which has all the combo organs in it. People will love that. I’ll buy one. Korg probably only talk to me because I’ll mention it in magazines like Electronic Sound, but things like that…” He points at the back cover of the album again. “That’s a Korg, that’s a Korg, that’s a Korg… All that was cheap. All the old drum machines, like the Korg Mini Pops… I got that for about £50.”

The discussion drifts from Korg to Roland and to how there was once a time when Roland 303s and 808s were also really cheap.

“I didn’t buy a 303 at the time because it didn’t look impressive enough, it didn’t look like it could do anything. It was too small. Which was foolish. They’re fantastic things.”

I tell Berry that I often used to see them propping open doors in studios.

“I know! The guy who does my synths was telling me these horror stories about how all the VCS3s were going into skips in the late 80s. Where was I when this was happening? I’ve had dreams about finding things like that in skips! The story with them is they were mostly in school and college music departments, just gathering dust, and the music teachers would ask the students if anyone wanted it. They’d all say no because it didn’t have a keyboard with it. You can imagine the kids saying, ‘Why the hell would I want that?’. So they gave the students first dibs and when they didn’t want them, they’d go in a skip. You see, that’s where I could have come in. I could have gone, ‘Yep! I’ll take that! And that other one!’.”

While it’s clear that Matt Berry’s electronic music influence comes from the Jean Michel Jarre side of the electronic envelope, where does the more accepted electronic music orthodoxy fit into his landscape? Wherefore art thou, Kraftwerk?

“I love all that as well, but I suppose I wanted to do something warmer and less austere. More inclusive. I think that’s what ‘Oxygene’ is, unlike ‘Man Machine’ or ‘Autobahn’. I really like them, but there’s a distance with those albums, whereas I think I’m right in the middle of my music. I hear everyone talk about the massive life-changing experience they had when they first heard or saw Kraftwerk, which I understand, but it’s not personal enough for me to have that kind of reaction, whereas ‘Oxygene’ is. And ‘Tubular Bells’ too. You can feel that the guy isn’t far away, whereas with ‘Autobahn’, not so much.”

As we end our conversation, Berry starts playing around with the melody he’d been working on when I arrived. He points at his Mellotron, the rather tasty Manikin Electronic Memotron.

“You know, Princess Margaret had one of the original Mellotrons,” he says. “Apparently she asked for hers to have the sounds of war on it. Explosions and guns. Extraordinary.”

‘Music For Insomniacs’ is out on Acid Jazz