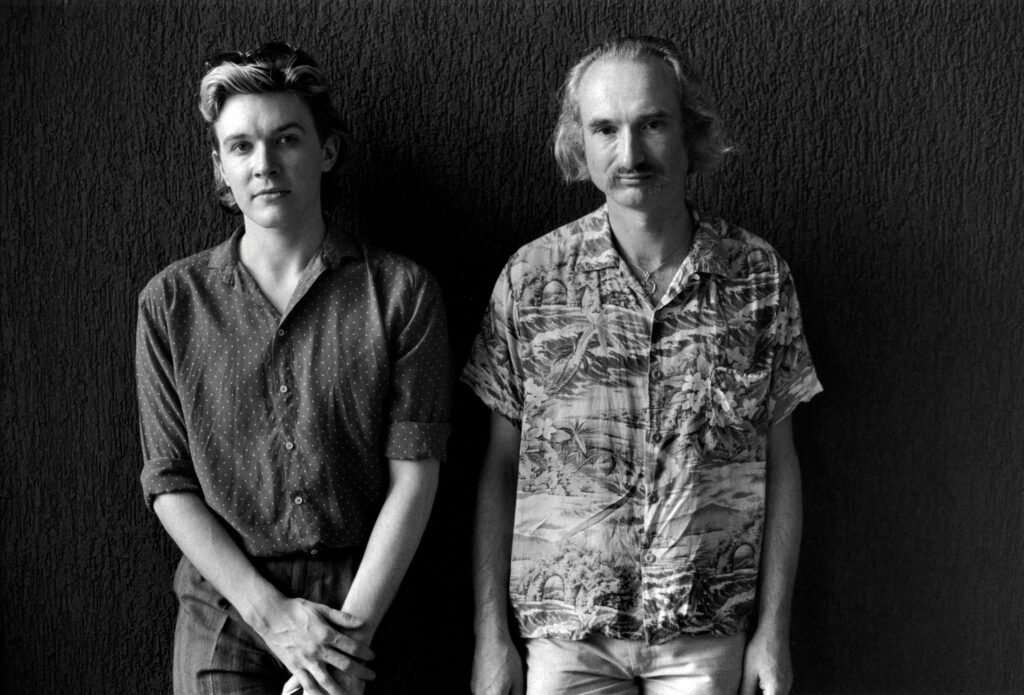

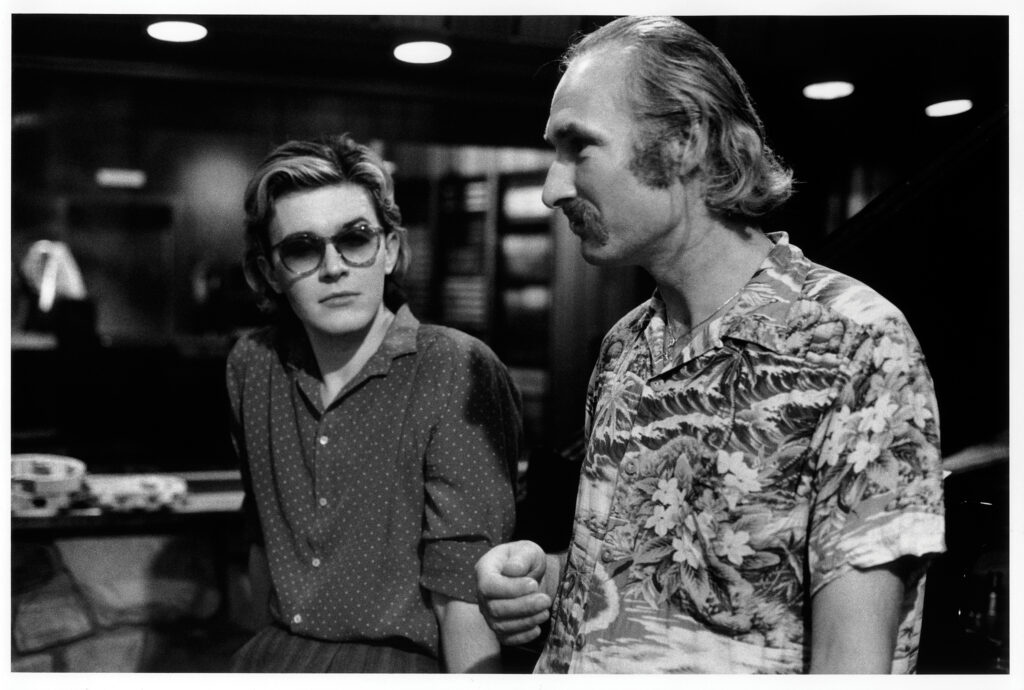

In 1986, Holger Czukay and David Sylvian met up at Holger’s converted cinema home/studio in Weilerswist, near Cologne. totally by accident they conjured up Aural magic. In a rare interview, David Sylvian discusses The fruit of the sessions, which are collected in a new boxset to be released later this month

Do you recall when you first became aware of Holger Czukay?

“It was around the time of the original release of ‘Movies’, so around 1979.”

How influential were Can and krautrock on you?

“They weren’t and it wasn’t. A lot depends on how fortunate you are to be exposed to a particular album at a specific point in your evolution as an avid listener. I was fortunate enough to hear The Velvets and Nico when I was 13 years old. If someone had introduced me to Lou Reed via his first solo album, it’s possible all potential emotional, empathetic, and artistic respect would likely have been lost to me for a period of time.

“So it was with Can in particular and krautrock in general. I was introduced to Can by their relatively late works prior to hearing the earlier albums that continue to make a potent impression, that still generate excitement and pleasure. Regardless, outside of my personal connection with the members of Can, a brief love of Kraftwerk, embracing the odd moment of crystalline beauty from the likes of someone such as Hans-Joachim Roedelius, the German music scene wasn’t of particular personal significance to me.”

Do you remember when you first met Holger?

“Yes, it was 1983. I’d invited him to Berlin to work on the early stages of the recording of ‘Brilliant Trees’. I was blown away by ‘Movies’ and wanted to bring something of his sensibility to play on ‘Brilliant Trees’. Everyone gathered there had specific roles to play, except Holger. I wanted a wild card; something, someone unpredictable whose input I’d not be able to anticipate. He was clearly an iconoclast when it came to recording techniques. I had to get a handle on how the man functioned in the recording environment. We first met on his arrival at the studio. He was calm, cheerful, excited, and unpredictable. It was also the first meeting between [Jon] Hassell and Holger since their time as students of Stockhausen too.”

He’s listed on the record as being responsible for “french horn, voice, guitar, dictaphone”…

“Holger was a far superior musician than people give him credit for. Yes, he dabbled with instruments in unconventional ways, instruments he clearly didn’t have any background training in, but, for example, he could also play beautifully ornate pieces on guitar.”

And the role of the dictaphone?

“He brought with him two large, antiquated IBM machines that he’d discovered dumped outside an office building in Köln. He recognised their potential and, back at the studio, started to explore the possibilities they presented. As he said, ‘I’ve so much more flexibility with these machines than any sampler on the market’ and, in general, this was the case.

“He’d improvise with samples, running the playback head of the dictaphone over a broad expanse of tape which he’d prepared with all manner of samples and sounds, many taken from his own studio environment, incorporating the use of the varispeed function which, as far as I’m aware, was the only other speed that the dictaphones had. It proved to be enough, in terms of flexibility, to produce sounds from which one frequently couldn’t determine the original source.

“On my material you can hear this approach employed on tracks such as ‘Weathered Wall’ and the coda to ‘Brilliant Trees’. On these songs, time was spent placing and occasionally repeating these unique elements to create motifs or meld together raw material into something that made sense within the context of the composition, but it was the beauty of the raw material that made this possible. After all, Holger himself would edit and rework his own material for extremely long periods.”

Did you cross paths with any other members of Can?

“I met Jaki [Liebezeit] many times as he frequently popped in and out of Can studios. He and Holger spent a good deal of time there and in various cafes around Köln. I also met and worked with Michael [Karoli] there. I was introduced to Irmin [Schmidt] via his wife who was managing Holger and the Spoon label at the time. We had dinner together in London once or twice.”

A silly question perhaps, but how has “ambient” music influenced you?

“Ambient as a genre seems to mean different things to different people. As far as I can discern, while [Eno’s] ‘Music For Airports’ is the classic of the genre, the first ‘ambient’ album I’d have heard would’ve been his ‘Discreet Music’, which I’d likely still listen to if I continued to believe, as I once did, that ambient was a genre that repaid repeat listening.

“These two recordings did once have a prominent place in my life, but to what degree they were influential I can’t say. ‘Another Green World’ was, in a sense, far more groundbreaking as it alluded to a number of genres or sub-genres to come, including that of ‘ambient’. ‘No Pussyfooting’ was one of the few albums I could afford to purchase when I was a teenager, so that had quite an impact on me. I’d also put a word in for Obscure Records as a label, which included Budd’s classic ‘The Pavilion Of Dreams’ – do we classify this as ambient? I personally do not, as it introduced a lot of young people to composers they might not have otherwise come across at an impressionable age.”

How would you define “ambient”?

“A home has been created for ambient music on such labels as 12k. The works are incredibly beautifully designed. I think that’s possibly the key term to use in this context. It’s music designed with a non-specific, but narrow function or utility in mind. It serves that utility – and I don’t mean to downplay its beauty nor its creativity by describing it thus – beautifully, particularly Taylor Deupree’s collection on the 12k label. This is possibly how we begin to narrow down which works might successfully be described as ‘ambient’ and which seem to skirt the boundary and its parameters.”

And with your own work? How does the term sit?

“I tend to avoid producing long-form pieces as they’re supremely demanding to produce and generally overlooked. ‘When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima’ continues where ‘Plight & Premonition’ left off, or rather, it’s one of many possible routes that could be taken, using it as a kind of ground zero. Ditto ‘When We Return You Won’t Recognize Us’. These aren’t ‘ambient’ works anymore than I believe ‘Plight & Premonition’ to be. ‘Flux’ can’t convincingly be labelled an ‘ambient’ piece. Of the four pieces that constitute this collection, the only composition I imagine falling into this category is ‘Mutability’.”

Following Holger’s work on ‘Brilliant Trees’, you reconvened in 1986 to record a vocal for ‘Music In The Air’ for his ‘Rome Remains Rome’ album. You didn’t actually record that vocal, did you?

“I didn’t record the vocal as we got completely immersed in the work that’d unintentionally surfaced during my 48-hour stay in Köln. I left for the airport directly from the studio. We’d forgotten about the original intention for my visit. Something rather wonderful had materialised in its place.”

The resulting ‘Plight & Premonition’ and ‘Flux & Mutability’ are described as “hidden gems”. Why have they remained hidden?

“I believe the rights to the recordings were returned to us some time in the 1990s. In the 2000s, Holger and I spoke of releasing a boxed set of the material adding numerous remixes to the original recordings. I’m in possession of at least three radically alternate remixes of ‘Plight’ which Holger had undertaken over the intervening years.

“In fact, I’d go as far as to say that Holger never let go of this material. It played an important and ongoing role in his life and in subsequent work of his own. Sadly, legal issues stood in the way of pursuing the release and the notion of the boxset faded from memory.”

Can you describe your first impressions of Holger’s place in Weilerswist?

“Can’s recording home was a beautifully lit, open space. The entrance to the building was dark, the box office still in place. Beyond that, a dark hallway led to a veil of curtains which, when pulled back, revealed the mixing console and beyond, the ramshackle, but oddly beautiful, reconditioned cinema.

“The walls were lined, floor to ceiling with mattresses, some of which were covered with a decorous variety of silk sheeting and quilts. There was no separation between studio and control room; there was just a large open space in which to work. The words ‘studio’ and ‘control room’ sound entirely inappropriate as no such conventions existed.

“Holger, laughing at the absurdity of his earlier set up, frequently told the story of how the first console he’d purchased simply had two settings, ‘loud’ and ‘soft’. Along the left and right sides of the room, a variety of instruments were lined up. Towards the back was a grand piano and behind that, at the very back of the room, Jaki’s set up.

The place clearly had an impact on ‘Plight & Premonition’ and ‘Flux & Mutability’?

“They wouldn’t have been created in any other location. Despite its size, this intimate space, with its very particular mood, distinct atmosphere, its spirit of unrestrained freedom, no fees, no clock ticking, was unlike any studio I’d worked in up until that time.”

The track titles are very evocative…

“Titles are generally of importance to me and can provide a variety of functions such as a possible hint at the essence of the work or additional element that helps define it. Or to possibly turn your head by its apparent lack of connection with the audio, provoking an imaginative leap of sorts, a personal filling in of the gaps. Again, these aren’t, to my mind, ambient works, so I’m speaking of titles in general. Frankly, ambient works could, and frequently do, have either very functional titles or something rather opaque – unyielding. I think the latter might be my preference.”

Of Holger’s arsenal of instruments, was there anything you didn’t recognise as being an instrument?

“One should really put analogue tape at the top of the list, at least during the period before digital became the main format of preference. His editing – splicing stereo and multi-track tape – was second nature to him. We’ve mentioned the dictaphone and then there was the shortwave radio.”

I like the idea that Holger was surreptitiously recording you playing. When did you realise what was going on?

“When he asked me to stop playing and move onto a third instrument. I’d started on the pump organ and moved to the piano. Just as I was finding a motif with which to work came the request to stop and move on. Holger was interested in the process of searching not of finding and refining.”

The first session was an all-nighter, wasn’t it?

“Yes, the bulk of the material was recorded over two consecutive nights. One can think of it as related to improvisation.”

How did the finished pieces come together?

“‘Premonition’ is heard more or less as it was completed that first night. ‘Plight’ went through a different process with extensive editing and additions made by Holger in my absence, prior to mixing.”

You talk about making “a form of music that seemed to have been created while we were absent, by instruments abandoned to the earth and the woods, sounded by the coarse winter elements”…

“Simply put, the presence of the musician’s ego is largely absented.”

You say these pieces are one of the few works you can actively return to and objectively enjoy as a listener?

“Yes, this is the case. Why? It’s possibly due to the absence mentioned in the previous answer.”

I always thought all the tracks came from the same sessions, but ‘Flux & Mutability’ was recorded at a different time, following your solo tour of 1988?

“It would’ve been futile to try and recreate the same set of circumstances that produced ‘Plight & Premonition’. Even the mood in the studio was markedly different from before. A new mixing console had been installed, an amenable, knowledgeable engineer, René Tinner, was occasionally present. Even the lighting had changed, or so it seemed to me. Everything about the space; its mood and atmosphere was somehow brighter. Ultimately, there were more musicians involved; Jaki, Michael, Marcus, and the work evolved in a more, let’s say traditional manner to the prior sessions. The focus shifted towards composition as opposed to pure improvisation or experimentation.”

As a listener, ‘Flux & Mutability’ sounds more musical, but sits beautifully alongside ‘Plight & Premonition’ as presented in the new set. How do you see it?

“They feel like two very different entities to me. The internal workings of the pieces; the means by which they were created, constructed; the degrees of conscious and unconscious searching, finding, failing, floundering; the level of pure intuition at work as opposed to the consciousness of the composer, differs from one project to the next.”

Did you expect these sessions to have the life they’ve had?

“As I hope I’ve indicated, during the process of its creation we both felt very excited by the material that became ‘Plight & Premonition’. We knew we’d conjured up something of some potency, a most unique ambience or, preferably, pieces that contained an uninhibited, expansive, power of evocation.”

Why do you think they still stand up today?

“Possibly because they’re not tied to any particular decade due to the largely unrecognisable fingerprint of technology utilised in the recording? Because the spirit conjured in the material is very much alive? There’s numerous answers to your question. Any and all might be valid.”

You revisited ‘Plight & Premonition’ in 2002, providing a new mix, which features in the new set. What prompted that?

“Prior to parting company with Virgin, I’d been asked to put together a couple of retrospective albums. The corresponding analogue multi-track masters I requested to work on had to be ‘baked’ so as to transfer them safely to digital files. It’s quite possible the entire catalogue would’ve otherwise have fallen into ruin.

“Virgin were infamous for the lack of care concerning their property in their vaults. For example, they erased a number of the multi-tracks containing material from ‘Tin Drum’. I used this opportunity to request more multi-track copies than I originally intended using. This is why I requested ‘Plight & Premonition’, but once I had the files in my possession I was tempted to see how I might ‘improve’ on the originals in terms of audio quality and what changes I’d be inclined to make.”

Which begs the question, why no new mix for ‘Flux & Mutability’

“I did remix a five-minute section of ‘Mutability’ for the same project. ‘Flux’ would be more of an undertaking, but potentially a worthwhile one. We’ll see what happens once Holger’s library has been catalogued. Maybe there’ll be justification for further examination of the pieces.”

Is there anything else up your sleeve featuring you and Holger?

“Other than more extensive remixes of this material we created, there is no other work together.”

It’s interesting that musicians revisit old works. Is making music like painting, where knowing when something is finished is instinctual?

“I was just having an exchange with Anton [Corbijn] regarding this issue. He was re-printing works for a couple of retrospectives. As we get older we’re constantly being asked to look back, which isn’t something we’re inclined to do, while at the same time we’re heartened to know that the older material holds enough significance that interest remains undiminished.”

You art directed the new artwork for this set, how was that?

“I enjoy art direction and being hands-on during the designing of the packaging. I’m all for creating new packaging for older works. If they’re going back into circulation I’d like to give them the best send off I’m able. I see no reason to remain unreasonably faithful to original artwork, especially if I personally have trouble embracing it.”

Did you and Holger stay in touch?

“We stayed in touch for many years. He passed through Minneapolis while I was living there; he opened for me one night, as part of a festival in the Netherlands as I recall, on my ‘Blemish’ tour. Towards the end of Holger’s life he fell silent. I tried to draw him out, I wished to visit him, but when he responded he sounded overwhelmed and entirely worn out by circumstances. I lost him as a dear friend prior to his passing.”

Looking back at the good times, these sessions are pretty high on your list?

“Yes of course, but I have many memories of my time with Holger. Hours spent together in our respective homes or local cafes, long walks through Köln or with my young family in a wintery Minneapolis. Listening to his many stories and his philosophy as it pertained to capturing and manipulating sound. And laughter; much laughter.”

‘Plight & Premonition’/’Flux & Mutability’ is released by Gronland