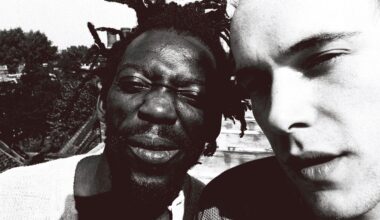

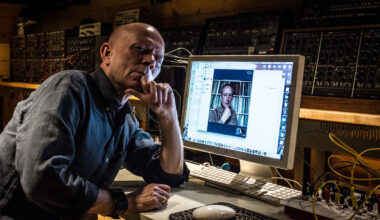

Daniel Robertson, founder member of Vancouver post-punk tearaways Crack Cloud, discusses the contrasting calm of his new solo project, Peace Chord

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here