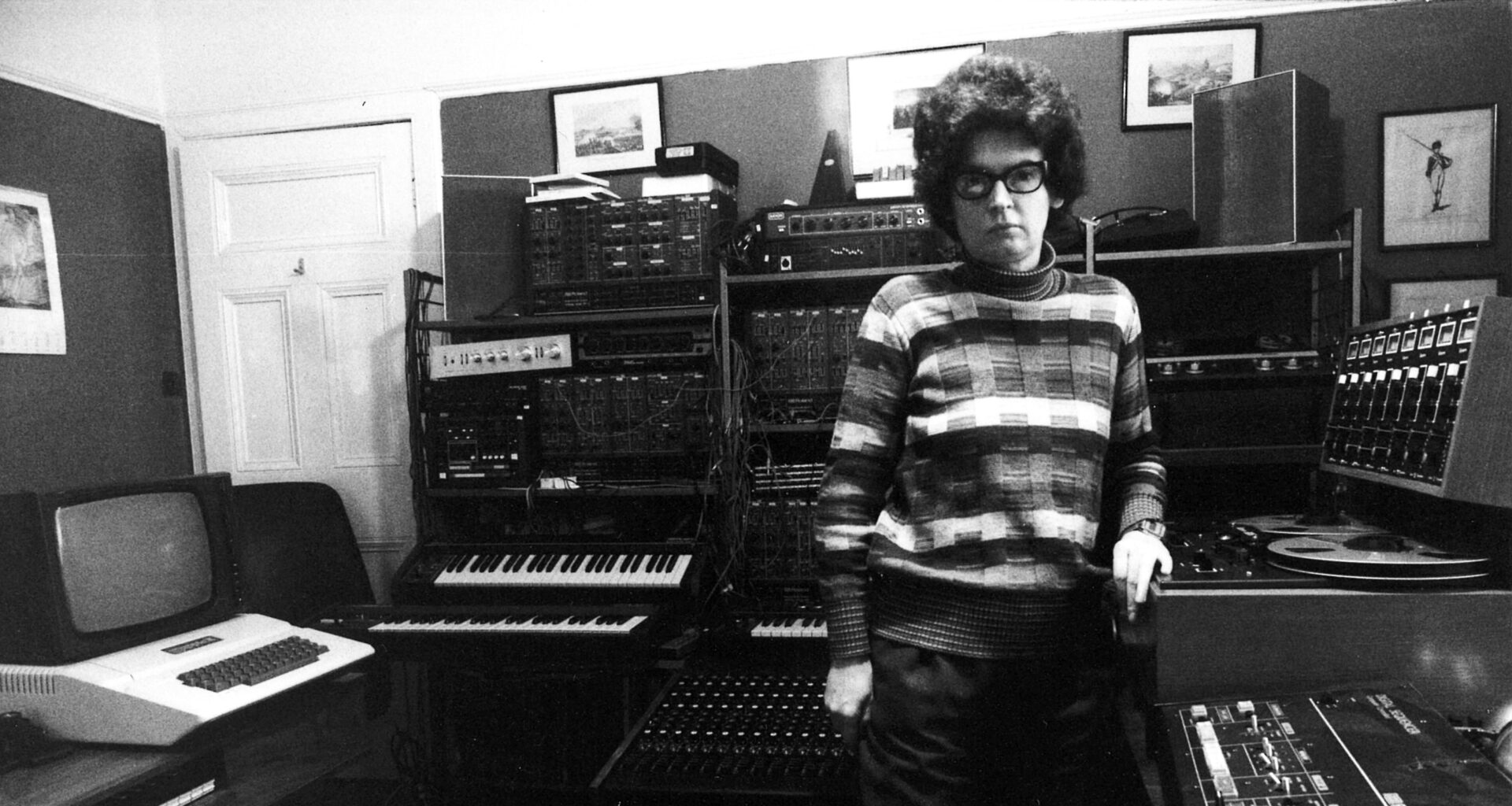

From wartime bombings to the creaking of tree bark, Janet Beat has always been fascinated by sound. Now in her 80s, this contemporary of Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire is finally being recognised for her pioneering electronic work

Want to read more?

Sign up to Electronic Sound Premium to gain access to every post, video, special offers, and more. 100%, all you can eat, no commitment, cancel any time.

Already a premium member? Log in here