It’s 35 years since Emma Anderson formed shoegaze behemoths Lush, but her new album ‘Pearlies’ is her first solo record proper. As both a paean to independence and a work of darkly beautiful psychedelic pop, it’s a triumph. What’s on her mind these days?

“Are you going to ask me about weird 1970s childhood TV?” says Emma Anderson, entirely out of the blue.

“Because I know you’re really into all that.”

Sometimes, it seems, one’s reputation precedes oneself. Go on then, let’s do this. What were the programmes that terrified her as a young girl?

“‘The Stone Tape’,” she replies without hesitation. “I had a TV in my bedroom when I was a kid. Not because I was a spoiled brat, but because I wasn’t really allowed to watch it with my mum and dad. I had a very odd upbringing. But that meant I could watch the telly until all hours, and I was absolutely petrified by ‘The Stone Tape’. I just remember the ending, with the lights… it’s Jane Asher, isn’t it? Not long ago, I watched it on YouTube, and it’s actually not that scary. But, as a child, I was badly affected by it.”

She wasn’t alone, I tell her. Nigel Kneale’s notorious 1972 BBC drama depicts an electronic research team haunted by the psychic echoes of violent, historical deaths embedded in the walls of their Victorian-built headquarters. It terrified everyone, despite a somewhat incongruous subplot about a revolutionary type of washing machine being developed by the boss from ‘Terry And June’.

“Ah,” she says, looking a bit bemused. “Sorry, I fast-forwarded it to the end.”

This might feel like a curious entry point for a conversation about Emma’s excellent new record, ‘Pearlies’.

But the weird disquiet of her 1970s youth and the resulting charms of 21st century hauntology were, she reveals, discussed in early planning sessions with the album’s producer, James “Maps” Chapman. With its tootling Farfisa organs and shuddering theremins, ‘Pearlies’ has the hallucinatory ambience of some strange, psychedelic childhood flying dream, swooping over frost-coated woods and waving at pipe-playing fauns watching ‘The Clangers’ on their own portable tellies.

“I did talk to James about all that stuff,” she says. “And about some of those artists. Do you know Baron Mordant, of Mordant Music? He was a dad from my daughter’s school and he lived next door to me. He’s a bit of that ilk, isn’t he? And have you heard of Concretism? I like his stuff too.”

Blimey, yes. Chris Sharp, from Essex. He makes beautiful electronic music inspired by his early memories of the 1980s Cold War. Although his last release, ‘The Thetford Beast’, was about a shaggy folkloric monster stalking the woodlands of Norfolk.

“I first came across him on Twitter,” says Emma. “Someone put up a clip about brutalist architecture and said, ‘What is this music?’. And it was so brilliant. It wasn’t on Spotify, and you couldn’t Shazam it, but someone else said, ‘Oh, it’s Concretism’.”

Has she heard of Warrington-Runcorn New Town Development Plan as well, I wonder? He’s made whole albums dedicated to town planning and the thwarted utopian visions of 1970s brutalist architecture.

“I have, because I remember the name!” she laughs. “Whenever I think of Warrington-Runcorn… one of my first jobs was working for the DHSS, basically paying people in the civil service their salaries. I had to write their names and National Insurance numbers on a massive pad. I was doing this in London, but they were then sent up to Warrington-Runcorn.

“And when I was younger, I remember thinking, ‘What am I going to do when I’m older?’. And one of my ideas was to work in town planning. I’ve always been fascinated by the whole ‘new town’ thing.”

So what was so “odd” about her upbringing? She takes a deep breath.

“God, I’m not sure we’ve got long enough. I grew up in central London, and my dad worked in one of those old boys’ army clubs where women weren’t allowed. It had big chairs, with old men drinking brandy. We lived in a flat just off Piccadilly, and I was there from the age of three to 15. It was quite a weird place for a child to grow up.”

And was Emma the rebellious teenager, terrifying retired brigadiers with her outlandish music tastes?

“We didn’t have a record player for years and years,” she recalls. “But my mum was quite a heavy smoker, so we finally bought one from the catalogue with all the cigarette tokens she’d collected. I didn’t have many records, and my mum and dad were older parents, so it was all Frankie Vaughan and Edith Piaf. But I had one of those little tape recorders with the buttons at the front, so I listened to The Beatles and Abba. Then, in my teenage years, I went off…”

She trails into laughter.

“I was into chart music first,” she remembers. “But then you discover the bands in the lower reaches of the Top 40, and you think, ‘These sound quite interesting’. I remember buying Smash Hits and looking at the indie pages – the first copy I bought had Crass and Cabaret Voltaire! This was 1981, so it was still a punk thing.

“Then, when I was old enough to go to gigs, I went to The Greyhound and The Clarendon in Hammersmith. My first gig was Japan at the Hammersmith Odeon, supported by Blancmange. So Blancmange were the first band I ever saw live, in December 1981. And I think my second gig was The Teardrop Explodes. I’ve got it written down somewhere. I also saw Haircut One Hundred and Duran Duran and ABC…”

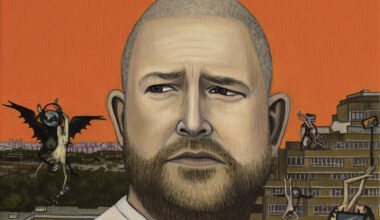

Photo: Brian David Stevens

I love the fact, I tell her, that she clearly kept meticulous records of the gigs she attended as a teenager. And that, despite immersing herself in the indie hinterland of pub backrooms and photocopied fanzines, she still cultivated an abiding love of mainstream, chart-friendly pop. She talks just as enthusiastically about Haircut frontman Nick Heyward as she does about her beloved Cocteau Twins. She nods enthusiastically.

“These were real bands,” she says. “God, Adam And The Ants came fully from the punk scene. And Bananarama had done the London clubs. The bands I was into as a teenager still had that punk or glam background – they’d liked David Bowie and Roxy Music. I actually feel quite lucky that these were the bands I grew up with.”

She pauses momentarily, clearly racking her brain for the contents of some long-forgotten gig ledger, written in faded biro and relegated to a dusty cardboard box in the loft.

“Actually,” she ponders. “I think I saw Haircut One Hundred twice.”

At is, however, the spirit of the Cocteau Twins that continues to haunt her musical adventures. Lush, the band she formed in 1987 with schoolmate Miki Berenyi, were among the first wave of bands to be labelled “shoegaze” – turning the Cocteau trademark of ethereal vocals and multilayered guitars into a movement that fluttered alluringly across the inky pages of the music press. They were even produced by Cocteaus guitarist Robin Guthrie. Three decades on, is the influence still being felt on her debut solo album? The title of ‘Pearlies’, I suggest, is surely a homage to her favourite band’s 1984 single, ‘Pearly-Dewdrops’ Drops’…

Apparently not.

“It was only when I was emailing Nat Cramp [founder of record label Sonic Cathedral] and I mentioned ‘Pearly-Dewdrops’ Drops’ that I thought, ‘God – the album title!’,” insists Emma. “It wasn’t that at all, but I guess it must have been in my subconscious. You’re the first person who’s said it. Where did I get it from? It might have been something to do with Pearly Kings and Queens. Or teeth. I just wanted something a bit playful.”

Nevertheless, she reveals, Robin Guthrie played a pivotal role in the album’s gestation, pooh-poohing Emma’s initial intention to enlist an alternate lead vocalist.

“The one thing he said to me was, ‘You’ve got to sing these tracks yourself, Emma – it’s time, and you can do it’,” she recalls. “I said, ‘I can’t’.”

Why the reluctance? She’d sung plenty of backing vocals for Lush before. And, indeed, her follow-up band Sing-Sing. Was it insecurity about her singing voice or a reluctance to be the centre of attention?

“A bit of both, I think,” she admits. “I’d just thought I couldn’t sing lead vocals. I’ve always been slightly on the sidelines, and I felt very comfortable there. But then I thought, ‘What’s the worst that can happen?’. And it’s been fine so far. At my ripe old age, I’ve suddenly taken the plunge.

“Initially, I came up with another name. I didn’t want it to be ‘Emma Anderson’, but Nat said, ‘Nope, it’s got to be your own name’, and I get why. I remember with Sing-Sing, a little American label released our first record and they said, ‘We want “Emma from Lush” on a sticker’. I was just…”

She makes a cringing face, as though someone has suddenly spilt cold custard all over her feet.

“But you have to do it, and I’m fine now,” she says. “It was just lack of confidence. And my name… you know, it’s the name I’ve had since I was a baby. ‘Emma Anderson’ [she says it as a childish playground taunt, mocking herself]. You hear it when you’re sitting in the dentist’s waiting room – ‘EMMA ANDERSON’!”

She laughs at her own self-consciousness, but the lyrics of the album reflect a burgeoning self-confidence, I suggest. “Swimming through space when time’s postponed / See if I can make it on my own,” she sings on ‘I Was Miles Away’. Elsewhere, there are hints of clean breaks from strained relationships, but she won’t be drawn on the finer details.

“There are a lot of lyrics that don’t really mean much at all, actually,” she says. “‘I Was Miles Away’ is just imagery and wordplay. ‘Willow And Mallow’ is the same. Fantasy situations.”

Unexpectedly, TV composer Ronnie Hazlehurst is namechecked in the press release for ‘Pearlies’. The folky ‘Willow And Mallow’, apparently, was partly influenced by his arrangement of the theme to Carla Lane’s uber-dark late 70s sitcom, ‘Butterflies’. The conversation drifts to other vintage comedies with bleak undertones – Emma cites ‘Ever Decreasing Circles’ and ‘The Fall And Rise Of Reginald Perrin’ as particular favourites.

“Even ‘Fawlty Towers’ is about a dysfunctional man having a midlife crisis,” she adds. “And that’s what we grew up with.”

She is earthily funny and utterly grounded – not just by the common currency of vintage television, but by the necessity of the nine-to-five. The sterling guitar licks lent to ‘Pearlies’ by Suede stalwart Richard Oakes were forged not, as you might expect, amid the hurly-burly of the 1990s festival circuit (“He was in the hotel with his babysitter,” quips Emma, in reference to his youthful start in the band), but in her current gainful employment as a bookkeeper. You know, accounts and spreadsheets and all that. Her clients, she reveals, include Suede’s current tour manager.

“I’d done office work before I was in Lush, then I started working again in about 2000,” she explains. “I had to knuckle down and get a job. I had a few royalties after we’d split up, but they… declined, as it were. I’ve actually worked in offices more than I’ve been a musician. Which I think surprises some people.”

Is this, I wonder, the secret side of stardom? It’s easy for fans to assume that anyone who has ever enjoyed a Top 40 hit spends the rest of their life in a mansion with gold taps. But, going back to Blancmange, their frontman Neil Arthur once told me there are very few pop stars who haven’t done a bit of painting and decorating on the side.

“Very much so!” nods Emma with a wry smile. “I’m still a bookkeeper – I did some work this morning. I actually like the autonomy. I’ve never earned enough… Lush didn’t sell a massive amount of records. It probably feels now like we were bigger than we were in the 1990s, but we never got a silver disc or anything. We were on an indie label. We did all right, but I think the appreciation of the band has maybe grown over time.”

Some of us were there at the start, I point out. Those 1980s Cocteau Twins singles that transport her back to her formative years as a music fan? My 1990s equivalent was Lush. Listening to the band’s earliest releases again, as I did in the build-up to our conversation, is a fast-track to my days as an excitable, indie-obsessed sixth-former, scribbling my own meticulous notes on the emerging bands I was reading about in NME and Melody Maker. And ‘Pearlies’ gives me the self-same feeling.

“Aw!” she grins, seeming both thrilled and genuinely surprised. “Thank you. That’s brilliant.”

It’s those psychic echoes again, isn’t it? Not in the walls of a spooky Victorian mansion this time, but in the grooves of a record that brings the ghosts of shimmering shoegaze glories floating into the crisp autumn air of 2023. Pearlies out, everyone.

‘Pearlies’ is out on Sonic Cathedral