Their new album, ‘Home Counties’, not only celebrates the leafy commuter belt burbs of their formative years, it also sees Saint Etienne getting back into the electronic groove of their prime

The British Library is thick with students who have come here to finish dissertations and revise for exams – more of them, in fact, than desk space will allow. As a consequence, the overspill is making the most of the spring sunshine. Textbooks and laptops are spread across the tables that surround the forecourt cafe.

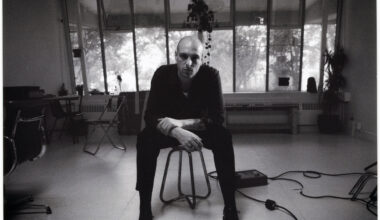

Among them, the members of Saint Etienne look slightly incongruous. Save for a sparse scattering of wiry grey-haired academics, they’re the oldest people in view. Bob Stanley stirs half a sachet of sugar into his latte and places his change on the table, a shiny £2 coin. Sporting full beard these days, Pete Wiggs picks up the money and reveals that, for no good reason, he once found himself reading the Wikipedia entry for the £2 coin.

“Guess how long these have been around?” he asks.

“Ooh, good question,” says Bob. “It’s bound to be longer than I think it is, because it always is. I’m going to say 12 years. Is it 2005? Whaaat?! 1998?! NO WAY!”

It’s at this point that the third member of Saint Etienne arrives. Sarah Cracknell is holding a cup of mixed berry tea, or as she calls it, “hot squash”. She reminds Bob and Pete about a game they used to play on tour in the early days of the band: £1 Newsagent, where they had to go to a random newsagent and find the best combination of items they could buy with £1.

“If we played it now, I think it would have to be £2 Newsagent,” she suggests.

It’s not inappropriate to be meeting Saint Etienne next to a building which houses countless national treasures. After all, that’s exactly what they’ve become in the 26 years since their debut album, ‘Foxbase Alpha’, catapulted them into the post-grunge, post-baggy bombsite of early 90s British chart pop.

If they had kindred spirits back then, they were few and far between. Possibly the Pet Shop Boys for the way they co-opted their influences into a sound that never wished itself back to a bygone era. Other spiritual fellow travellers included Pulp, World Of Twist and Denim. Like Saint Etienne, these groups were part pop stars, part outsider artists working to a rigid list of dos and don’ts, spending almost as much time getting their sleeve art right as their music. And like Saint Etienne, these artists understood that a non-musician who talks a good record will always make better art than a musician who equates virtuosity with honest-to-goodness authenticity.

Saint Etienne’s early roll call of hits bears extraordinary testament to that very approach: their lugubrious dancefloor dub reconfiguration of ‘Only Love Can Break Your Heart’; ‘Avenue’, which recast their love of French baroque pop amid the unearthly magic hour stillness more commonly found on records by dream pop contemporaries AR Kane and Disco Inferno; ‘Like A Motorway’, an old folk melody delivered with statuesque sadness by Sarah over an irresistible disco-concrete instrumental; and, of course, ‘He’s On The Phone’, their biggest hit, and still a flawless slice of surging yet melancholy Europop.

Ironically, they’re still here today because, at any given time, they always held something back. Each Saint Etienne record sounds like a bridge to the next one, rather than the culmination of the previous ones, be it 2000’s ‘Sound Of Water’ (which saw them go to Berlin and work with electronic post-rock trio To Rococo Rot) or 2011’s ‘Words And Music’, an album about how music soundtracks your life and, in doing so, explains your life to you.

The opening song of ‘Words And Music’, ‘Over The Border’, talked about the obsessive behaviour that the love of records can drive you to: “I didn’t go to church / I didn’t need to / Green and yellow Harvests / Pink Pyes, silver Bells / And the strange and important sound of the synthesiser”. Its poignant air of finality led many people to suppose that this would be the final Saint Etienne record…

“I think we wondered that ourselves,” notes Bob, who became a father for the first time last year. “In a way, a band is a funny thing to keep going beyond your early 20s, because it happens at a time in your life when you’re no longer living at home, but you’ve yet to settle down and start a family. It sort of fills that vacuum. And during that time, Pete and I were actually living together.”

“Those were your ‘Men Behaving Badly’ years!” says Sarah, clearly amused by the idea.

“Except we didn’t behave very badly, did we?” says Pete, parrying the question to Bob.

“We had a party once, didn’t we?” replies Bob. “And Mark Hollis from Talk Talk turned up. This was in the mid-90s, when no one had seen him for years, and there were all sorts of rumours going around about what sort of state he was in. One of the guests brought him along, I had no idea she knew him, and I involuntarily exclaimed, ‘You’re Mark Hollis!’. And he left almost immediately. I really blew it there, didn’t I?”

Back in those early years, Saint Etienne was an expression of an interior world Bob and Pete shared long before they lived in the same house and long before they asked Sarah to join the group following her vocal turn for 1991’s ‘Nothing Can Stop Us’.

They were best friends from infant school in Reigate. Bob read ‘The Dandy’, while Pete favoured its racier southern rival ‘Whoopee!’. Pete would go to Bob’s every Thursday to watch ‘Top Of The Pops’. One of their fondest memories concerns the night in 1982 that Culture Club first appeared on the show.

“My dad came in and saw Boy George looking the way he did and asked if that was a boy or a girl. Obviously, Pete and I found this hilarious, which merely served to rattle him further. At which point he said, ‘Well, you wouldn’t be laughing if I came in looking like that, would you?’. We almost exploded!”

The following year, 1983, was when Bob began to plan his pop dream in earnest. Aged 17, he was “blown away” by OMD’s ‘Dazzle Ships’ album and saved up to buy a Korg MS-10.

“Years later, I read that Juan Atkins had also bought a Korg MS-10 round about the same time,” he says. “He was out shopping with his mum, saw it in the store window, and persuaded her to buy it for him. He went on to invent techno, whereas all I used it for was to make wind noises.”

Not much seems to have changed in the intervening years. Even now, Bob’s preferred songwriting method is to hum tunes into his phone or bring a record into the studio and enlist the help of the producer to replicate a particular sound. For the longest time, this was also the method favoured by Pete, but after composing the BFI-commissioned soundtrack for ‘How We Used To Live’ – the 2013 visual love letter to post-war London that the band made with long-time collaborator Paul Kelly – he enrolled on a composition and orchestration degree course.

“It’s amazing how you can get by on so little sleep,” he says when asked how it’s going. He does most of his composition work before dawn, in his Brighton kitchen, often as early as 4am, before his son and daughter wake up. “I rather like it, actually. You feel virtuous when you’re working alone and it’s still dark outside. I get to pretend I’m the man on the sleeve of Donald Fagen’s ‘The Nightfly’.”

The new Saint Etienne album is ‘Home Counties’, their most uniformly satisfying set since 1993’s ‘So Tough’.

Like that record, ‘Home Counties’ is an immersive experience in which industrially adhesive pop songs – ‘Out Of My Mind’, ‘Heather’, ‘Take It All In’ – are linked by evocatively-titled mood pieces such as ‘Church Pew Furniture Restorer’, ‘Sports Report’ and ‘Popmaster’. The latter sees a guesting Ken Bruce hosting a special version of his ‘PopMaster’ Radio 2 quiz slot, in which the contestant is asked to name three Top 10 hits by Hatfield And The North (there aren’t any, by the way).

“That was the most exciting day of the sessions, wasn’t it?” says Sarah.

Bob’s expression, however, is somewhat pained.

“I love Ken Bruce, but we committed a slight faux pas,” he explains. “He recorded his bit really quickly, like the pro he is, and then he sort of said something which sounded like he was suggesting we might all go to the pub together. But I wasn’t quite sure that’s what he meant… and then he hesitated and backtracked. I’d love to have gone for a drink with Ken Bruce. I listen to ‘PopMaster’ every day.”

As befits an album inspired by the commuter belt conurbations orbiting London, Saint Etienne approached ‘Home Counties’ on a strictly nine-to-five basis, completing all the songs over a six-week period at the end of last year. They had no idea what the album would be about when they commenced the sessions. On a songwriting roll after finishing her feted 2015 solo album ‘Red Kite’, Sarah presented Bob and Pete with two of the album’s standout tracks right at the beginning of the process: the hammock-swinging languor of ‘Take It All In’ and the Casiotone Latin hustle of ‘Dive’.

“For some reason, both songs got me thinking of the Metro-land world you see speeding by when you’re on a train heading out of London,” says Bob.

In turn, that prompted Bob to come up with another of the album’s highlights, written partly in tribute to the late Nick Sanderson from Earl Brutus, who finally realised his childhood dream of becoming a train driver once the group had disbanded.

“He used to go through Whyteleafe,” says Bob. “I told him you could see Whyteleafe’s football ground from the line and he said, ‘I can’t look, Bob. I can’t take my eyes off the track. I’m just petrified the whole time’. He’d heard stories of people dropping things from bridges and throwing themselves on the track. It wasn’t anything like the one-hand-on-the-wheel, admiring-the-view idyll that he had hoped.”

The tidal push and pull between London and the commuter belt has always been an object of fascination for Saint Etienne. You’ll remember the ‘Billy Liar’ sample at the beginning of ‘You’re In A Bad Way’, in which our daydreaming hero is warned by his boss Mr Shadrack that “a man could lose himself in London”. In a way, it’s perhaps surprising that it’s taken until now for them to devote an entire album to the “sweet municipal dream” of leafy conurbations such as Breakneck Hill and Woodhatch. From its exquisite harpsichord intro, ‘Whyteleafe’ billows softly out into a pensive rumination, loosely based on one of Bob’s old school friends who never ventured beyond the square mile where he grew up.

The penultimate song on the record, ‘Sweet Arcadia’, is the breathtaking culmination of everything preceding it. An eight-minute rolling-stock elegy to the myriad versions of England that act as co-ordinates on the mainline routes to the satellite towns of London. You suspect that, in time, it might serve as the basis of a future Saint Etienne film, a home counties counterweight to ‘How We Used To Live’.

“I can imagine that,” concurs Bob. “I think we all enjoy hearing ideas from people about what would constitute a Saint Etienne project.”

Saint Etienne is no longer the full-time occupation that it used to be, though. Sarah has already started work on her next solo album and then there’s the business of being a mum to two young QPR fans. When he’s not walking his son Leonard around north London in the BabyBjorn, Bob is hard at work on the follow-up to ‘Yeah Yeah Yeah’, his acclaimed 700-page history of pop. And Pete, of course, the Brighton Nightfly, has symphonies in his sights.

Yet for all of that, Saint Etienne is still their default, the thing that most feels like home. On the table next to us, Pete’s children have been fixed on their iPads, waiting for their dad to finish here before paying a visit to the Tate Modern. Bob is heading into the British Library to continue work on his book, while Sarah is off home to pack for a holiday.

Before parting ways, there’s just enough time for a quick round of £2 Newsagent. Bob’s having the latest ‘Non-League Paper’ and his chocolate of choice, a Twirl. Pete’s given up sugar, so it’ll have to be a bag of cashews for him. Sarah goes for her favourite sweet treat, condensed milk – “preferably a tube, so I can stick it straight in my gob,” she says. “Sometimes I even keep one in my handbag!”

“There you go,” says Bob. “That’s a proper pop star for you. Condensed milk in her handbag. They don’t make them like that any more.”

They really don’t. How wonderful to have them back.

‘Home Counties’ is released by Heavenly