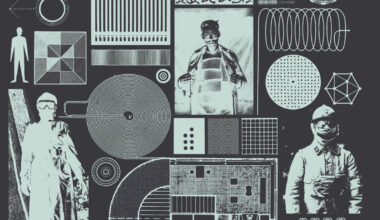

With just three instruments between them, how is that Manchester’s Gogo Penguin sound so familiar? We lift the lid on their jazz-like exterior and find out how they do live electronica… with no electronics

“I think it’s because we’re stupid and we like to make things really difficult for ourselves,” laughs Chris Illingworth from GoGo Penguin. They’re the Manchester trio that Illingworth makes up with drummer Rob Turner and bassist Nick Blacka, who look, feel and occasionally sound like a jazz group, but aren’t. He is referring to the band’s insistence on only ever making music acoustically, a technique they have used unswervingly across their four hypnotic albums, from 2012’s,‘Fanfares’ to their recent beguiling ‘A Humdrum Star’.

To be expressly clear, that means no synths, no post-production interventions, no optimisation – nothing but piano, double bass and drums. Yet the members of GoGo Penguin think of themselves as electronic musicians first and foremost because of how they compose their music, using synths and software at the composition stage, but then removing them in a manner reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘Erased de Kooning Drawing’.

The result is music that is electronically conceived, just not electronically realised; jazz but not quite jazz. This is the weird, oxymoronic story of a group that could very well forever alter your notion of what makes electronic music electronic.

From the off, GoGo Penguin wanted to be different, even if outwardly, they look a lot like any other jazz trio. Chris Illingworth recoils a little at the association with that tradition.

“We started out with piano, bass and drums because those were the instruments that we played, not because we set about to make jazz,” he insists.

Nevertheless, GoGo Penguin came up through the Manchester jazz scene. Illingworth had been studying piano at music college in Manchester, venturing from classical austerity to performing in various groups, which is how he, Blacka and Turner initially connected. He just wanted to play in a band, with like-minded musicians, and the style of music wasn’t that important to him.

So keen were the nascent trio to distance themselves from any genre-derived trappings that they came up with a nonsensical moniker instead of, say, the Rob Turner Trio. GoGo Penguin immediately sounds more like a tech start-up or a Dadaist proclamation than a group.

“We wanted to say to people that we’re not a jazz band – we’re just another band with a silly name,” he asserts. “We came up with something at short notice before we had to go and do a gig. It just seemed to fit.”

In spite of a reticence about being seen as part of the scene they emerged from, there’s a definite leaning to a fluid, free sound on their debut album, ‘Fanfares’. By 2014’s, ‘V2.0’ and 2016’s, ‘Man Made Object’, the electronic influence is much more identifiable. Lines are more focussed, rhythms more complex and the drum patterns more adventurous; Illingworth’s piano veers from rave-y urgency to hauntingly simple Aphex melodies, and the trio handles abrupt halts, pivots and restarts that sound a lot like Oval’s skipping CDs.

With some irony, ‘Man Made Object’ was GoGo Penguin’s first album for Blue Note, a label that is synonymous with jazz, issuing landmark albums by Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins and countless others.

“It’s pretty weird,” Illingworth concedes. “Three white guys from the north of England signed to Blue Note. The guys at the label saw us play a gig in Germany and they were really into it. Within a week there was an offer on the table.”

Which perhaps isn’t so strange.

“The core thing about jazz is freedom,” Illingworth impresses. “Unfortunately, there’s these traditions, these kind of unspoken agreements about what you can and can’t do. There’s even a jazz piano textbook that tells you how to play jazz piano exactly like everybody else’s jazz piano. But the core of jazz is just pushing boundaries and trying to do different things, trying to make music that you want to make with a lot of freedom. That’s what Blue Note want. They’re very aware of that as part of their legacy, and that’s what they saw in what we were doing.”

Let’s turn away from the debate over whether GoGo Penguin are jazz or not and instead ponder the divisive question of how a group that only ever performs acoustically can consider themselves electronic.

“We use a lot of electronics when we’re drawing the original sketches of ideas,” Illingworth explains. “We’ll write stuff using Logic or Reason or Ableton, but then we make those pieces acoustically.”

Simple, right? That is until you hear a track like ‘Garden Dog Barbecue’ from ‘V2.0’. Here the trio approximate Orbital circa ‘Kein Trink Wasser’, yet abruptly turn on their heels and hammer out highly intricate back-and-forth switches that leave you feeling like some sort of electronic processing must have been involved. It’s the only logical way to explain the alien, robotic, inhuman dimension on that track.

“I’ve been playing the piano since I was eight years old, and sometimes it’s difficult not to just play on autopilot and do the same thing every single time,” he says. “The reason I started using electronics to compose was to just get into a different mindset. So I’ll write something with no thought as to whether it’s possible, and then we’ll try and work out a way of playing it. We’re not worrying about whether it’s physically playable at that point.”

Illingworth dates his love of electronic music to first hearing the likes of Underworld when he was 11 years old. He would come to see a similarity to what became GoGo Penguin in the way tracks from ‘Second Toughest In The Infants’ emerged out of rough sketches and demos, not just sequenced pre-programmed ideas.

“I’ve always loved playing with synths,” he continues. “I’ll start messing about with a patch, and I’ll think about how I could alter the attack and decay. But it’ll just come to a point where I’ll try to use the techniques I learned in classical music to create that same idea with the piano.”

He goes on to explain that the meticulous way that Turner prepares his drum kit allows him to craft something close to detuned kick drums, 808 patterns, claps and other hallmarks of the electronic rhythm play-book.

“As soon as you do that once, it’s addictive,” Illingworth muses. “There are moments where we know we could use a synth, or electronic effects, or we could create it all through a studio, but that’s the challenge. We want to see how far we can get, even if it is hard work.”

“Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe, in which there are far more galaxies than people.”

Those were the words of scientist Carl Sagan, from his 1980 TV series, ‘Cosmos’. ‘A Humdrum Star’, GoGo Penguin’s new album and title was inspired by Sagan’s rumination on humanity’s tiny place in the universe, a thought that renders all of our individual achievements virtually pointless in the context of the vastness of space.

Another reference point was Sagan’s 1990 request that the Voyager probe turn back and take one last photo of Earth as it left the Solar System forever. In that photo, known as ‘Pale Blue Dot’, Earth is but a speck viewed from a vantage point of some six billion kilometres into deep space. It is a concept that is both wonderful and harrowing.

“It’s something we’ve all been fascinated by,” Illingworth reflects. “We realised that ‘Pale Blue Dot’ was an exact picture of who we are at this moment as a band. All the experimenting and touring has led to this point and this moment, and then that’s going to be gone. We’ve gone through this big build-up to this album, then we made it, then it was done, and then it just becomes this little icon you can see on iTunes. It doesn’t make it any less important, or any less special – it’s just a way of looking at it from a different perspective.”

This powerful idea certainly gives ‘A Humdrum Star’ a more muted air, and one that is slightly less glitchy. Still, true to the challenge these three players have continually set themselves, it carries an electronic quality that leaves you convinced that a measure of studio trickery must be at work. As tempting and efficient as it might be, GoGo Penguin have once again left the synths in the writing room. The only bit of additional kit here is a small pedal that produces sustained notes and textures from the piano and bass, but Illingworth is at pains to stress that this isn’t cheating.

“It’s still just an acoustic instrument feeding into that,” he argues. “It basically records a split-second of whatever sound you’ve captured and maintains that. It’s like using a sustain pedal at a piano, but you’re just stopping the sound from decaying, which is the natural thing that it wants to do.”

The pedal receives liberal use on the new album, particularly on Blacka’s bass sections on ‘Bardo’. With its serene ambient opening section, ‘Bardo’ represents one of the album’s many highlights, but it also deploys a much more traditional effect and one that cements GoGo Penguin’s ambition to deliver electronic sounds unelectronically.

“The chords and melody that you can hear at the beginning, that’s just from muting the strings. It’s a really simple effect. We found this stuff that’s like Velcro, which you put on the strings. It just creates a really good, almost rubber bass synth sound – but it’s still totally acoustic.”

Having mastered an approach that simultaneously messes around with your impression of electronic composition and whatever preconceptions you might hold about jazz, it’s easy to see how GoGo Penguin could continue to challenge themselves without feeling especially limited.

“One of the things we’re trying to play around with at the moment is incorporating more prepared piano,” Illingworth suggests, citing the influence of John Cage and his landmark piano manipulations. “You can get some amazing sounds, but the problem is how long it takes to set it up. I used to do some prepared things when I was studying classical piano, and I’d take maybe half an hour to set up the piano, so it’s not practical if we’re using it in a gig where you’d need to take all the nuts and bolts out of the piano in between tunes.”

I argue that it would surely be impossible to build and rebuild a prepared instrument on a whim, and that the effect could easily be written electronically, but that’s exactly the kind of thing that Illingworth loves to hear.

“Once you say it’s not going to happen we’ve got to find a way to do it,” he says, finding yet another rule book to rip up. “We’ve just got to.”

‘A Humdrum Star’ is out on Blue Note