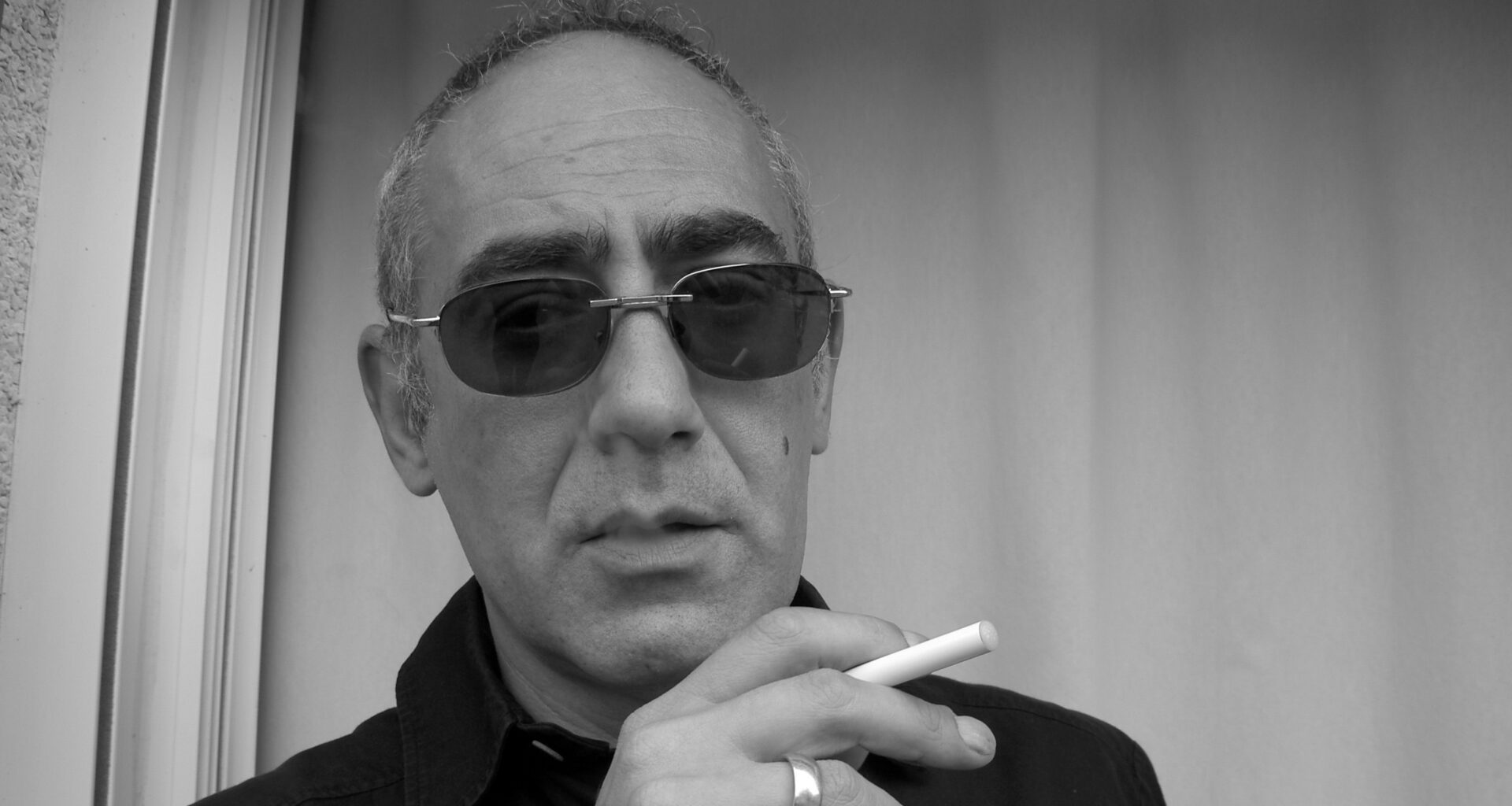

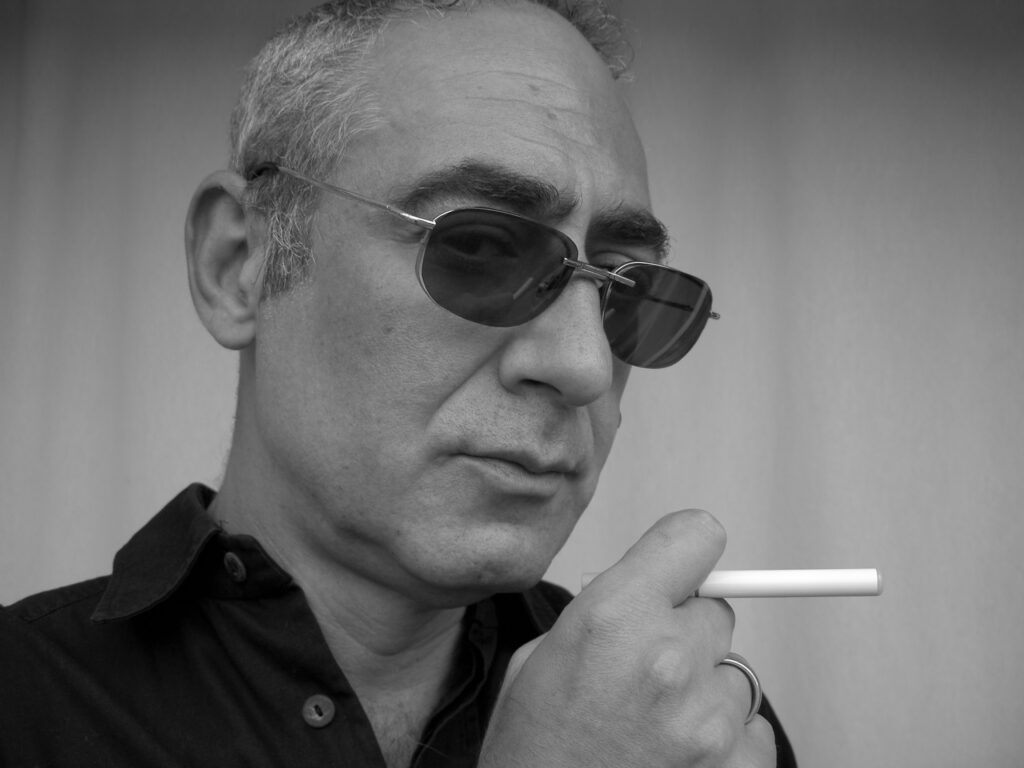

With the release of his new solo album, ‘2’, DAF man Gabi Delgado talks about his days as a Düsseldorf punk, his dislike of analogue synthesis, and how his recent move to Spain has re-energised his creative drive

It’s a warm autumn evening in Andalusia. Chickens are clucking, dogs are growling at shadows, and the sun is slowly setting over Gabi Delgado’s back yard. He takes a swig from a bottle of Coke, lights a cigarette, exhales deeply, and promptly begins complaining about modern music.

“Give me 100 electronic tracks and I’ll bet that the bass drums come in at either bar 17 or bar 33. It’s all so obvious. An important essence of music is to make people lose control. It ties in with ancient societies and rituals, where you have people getting put into a trance and losing it through music. I think it’s a function of music to make people experience other things, outside of normality and reality, just through feeling and dancing.”

Delgado has just released ‘2’, a new solo album chock-a-block with the characteristically brutal rhythms that have dominated his work since forming Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft with Robert Görl in 1978. The album consists of 32 tracks – 40 if you’re a member of Delgado’s music club – and arrives hot on the heels of 2014’s ‘1’ and the download albums ‘X’ and ‘Club Worx’. Which brings the total number of tracks released by Delgado in the last two years to more than 80, a prodigious body of work that puts many other creative souls to shame.

“There are a few reasons for that,” explains Delgado. “The first is simple – I want to give people value for money. I get fed up when CDs have just 10 tracks, especially when I know that eight of those are there to fill the fucking album. The second reason is that it’s a statement. There’s a general tendency – in society, in economics, in politics, in art, even in people’s private lives – to not give everything. Austerity is a principle I don’t like at all. People are not able or prepared to give everything today, but I like to give everything.

“There’s also an artistic reason, which is that a lot of the time I like to discharge everything I have in my head in order to be able to start new things. That’s done now. Now I have room for new ideas, new tracks, new things.”

DAF were a product of the late 1970s Düsseldorf punk scene. Whereas UK punk was rooted in social angst and political disenchantment, Düsseldorf’s punk movement, like that of New York, arose from a much more artistic aesthetic.

“Düsseldorf was a rich city, a very rich city, one of the richest cities in Germany,” says Gabi Delgado. “All the old industries – steel and mining – were still running and the offices and the profits for those companies were in Düsseldorf, so lots of families had a high standard of living. The kids could afford guitars and synthesisers and home studios, which in those days were very expensive. On the other hand, there was also a strong arts scene. Joseph Beuys was teaching at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, for instance, which is one of the leading arts schools in Germany.

“At that time, everybody in that whole area who wanted to go out had to go to Düsseldorf. There were better discotheques, better clubs and better bars, so it was a real melting pot. And the kids in Düsseldorf were always looking out for what was new. They were the first to discover punk in Germany, apart from the Berliners. There was a club in Düsseldorf called Ratinger Hof, and in 1976 it became our meeting point for the punk movement.

“It was a nothing place, with no particular style, but it was rough enough. The owner of the club was Carmen, who was the wife of the famous German painter Imi Knoebel, and she decided to give the punks this space. They put up some neon lights, so it wasn’t too dark and it also wasn’t too hippy. It was a totally open scene, it wasn’t about who you were or where you were from, so very soon the students from the arts academy came to the Ratinger Hof too. For us, it was like the Cabaret Voltaire was for Dada. It became a beacon for what was going on in our punk scene.”

Despite being smitten with punk, Delgado wasn’t a fan of rock ’n’ roll. Or guitars.

“Punk had this fresh, new, radical energy and I couldn’t understand why it was based around such old instruments,” he says. “You can’t do much with a guitar, especially if you can’t play it. For me, a band like The Ramones was just one big, endless song. It fell to us to put the synthesiser in the middle of that – and that was beginning of Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft. The music DAF played still had rock ’n’ roll harmonies, which linked it to punk – punk was just badly played rock ’n’ roll, after all – but we were using electronic machines not guitars.”

During his pre-punk days, Delgado had been schooled in disco music, Giorgio Moroder especially, as well as P-Funksters Parliament and the more jazzy Weather Report.

“So I knew there were more interesting and wider possibilities for music than just the dum-dum-dum of punk,” he offers.

Around the same time, he began to become more aware of Germany’s own electronic music tradition, discovering bands like Neu! and Tangerine Dream. But he wasn’t so keen on Kraftwerk.

“Kraftwerk were not accepted in the Düsseldorf punk scene at all,” he laughs. “The punks saw these guys with their ties and they knew they were from the other side of the Rhine. The left side of the river is very chic and posh, and Kraftwerk were always going around there wearing their ties, drinking milk drinks in this bar called Milk Bar 2000. The punks thought Kraftwerk were posh arsholes. It wasn’t until much later, in the early 80s, that they started being celebrated. But in the punk days, no way.”

Although Delgado can now appreciate what he describes as Kraftwerk’s enormous historical significance, at the time he thought they were too safe. He also thinks they missed an opportunity by focusing too heavily on album-based concepts and classic pop song structures, rather than the long and flowing tracks they recorded in the early part of their career.

“Their sounds became too clean,” he explains. “I love machines, but I love machines that have more of a sense of danger. You know, one wing is burning, but you’re still piloting the thing. There wasn’t enough danger in Kraftwerk. Their music was like being sat in an office. DAF were totally different. We didn’t want to have a verse, an A part and a B part. We wanted one constantly moving machine that just goes on and on, only changing slightly, and that’s how club music is today.”

To reinforce the point, his ‘2’ album opens with the blunt ‘NDKM’, which stands for ‘Neue Deutsche Klub Musik’.

“I’m really referring to what is going on nowadays in German clubs outside of Berlin,” says Delgado. “What’s interesting is we’re hearing combinations of tracks that five years ago would have been unimaginable. Neue Deutsche Klub Musik is all these styles coming together, as they do in ‘NDKM’, where you have a half-beat part, more of a hardstep edge to the sound, and a part that’s more techno.”

But while ‘NDKM’ is a celebration of the new, ‘Gott Ist Tot’ (‘God Is Dead’) amounts to an obituary for what Delgado perceives as outdated religious belief systems.

“I wanted to put out the statement that it’s not really necessary for modern people to believe in God, or even heaven,” he says, as a dog begins howling ominously behind him. “To me, there are no longer any sins, so there is no need to feel guilty.”

Don’t let this make you think ‘2’ is all heavy stuff, though. At the other extreme of the album is ‘Elektro Punk Kung Fu Meister’, a light-hearted track loaded with hubris that Delgado wrote because of his childhood love of Bruce Lee.

From God and Bruce Lee, our conversation moves on to analogue synthesisers. More and more bands are getting into the retro equipment market, trying to emulate the sounds of the 1970s and 1980s. But according to Delgado, analogue synthesis is something else that should be “tot”.

“I think there’s a lot of hype around it,” he sighs, both sounding and looking deflated. “I think that the modern Nord synthesiser or an FM synthesiser sounds much better than an analogue synth. You can do much more interesting things with FM synthesis.

“I get lots of people contacting me to tell me they have just bought a Korg MS-20 but they can’t get it to make the sort of sounds we made in DAF. When we went to Conny Plank’s studio, Conny said the sound was so plastic, so cheap. He said it had no power. Conny’s idea was to put the Korg through big Marshall guitar amps and run bass sequences through Trace Elliot boxes. That was the secret of the DAF sound. We’d then put them in the room and record using microphones, like a rock band would do. It gave a warm distortion, but also the sound of the room.

“It’s true to say that I’m not a nostalgic person. I don’t understand people who own a hard disk recorder and a 4K television, but prefer VHS videos! Of course, everything old has its charm, but when people buy analogue synths I think they’re spending money in the wrong place. They’re antiques. It’s like wanting to have a Mercedes Benz from the 1960s. I don’t get it. You can’t travel back in time.”

For someone so obsessed with progress and so dismissive of any sort of legacy, Delgado’s recent move back to his native Spain could be seen as an attempt at turning back the clock. He was born in Andalusia, but moved to Germany when he was young to join his father, who had fled from General Franco’s oppressive political regime a few years before. His return to his roots might suggest he’s edging towards retirement, but Delgado laughs this idea off.

“I just wanted a simpler life,” he says, taking another glug of his Coke. “I lived for a long time in Berlin and I was really fed up with the weather. In Spain, we have lots of sunshine all through the year, but also the mentality here is so different. Germany is a very regulated country. Everything needs a permit and you must double check all that you do with a lot of bureaucracy.”

As well as prompting a period of incredible creativity, Delgado’s move back to Spain has allowed some clarity to emerge about the future of DAF and his on-off partnership with Robert Görl. The pair have reunited several times over the last decade or so, but announced they had split for good earlier this year. Now it seems they’ve reversed that decision.

“We have decided to carry on, but just as a live project,” confirms Delgado. “Robert was here in my home studio in Spain recently and we tried a few things out, but the problem is we are both very radical. If we don’t agree completely, then we don’t want to compromise. We couldn’t find an approach that suited us both, but we will be continuing to play live, so who knows where that might lead.”

God and analogue synths might well be dead in Delgado’s view, but for now at least DAF lives on.

“We’re definitely not stopping,” he insists, before heading back into the sonic research lab this electropunk kung fu master calls home.

‘2’ is out on Oblivion/SPV