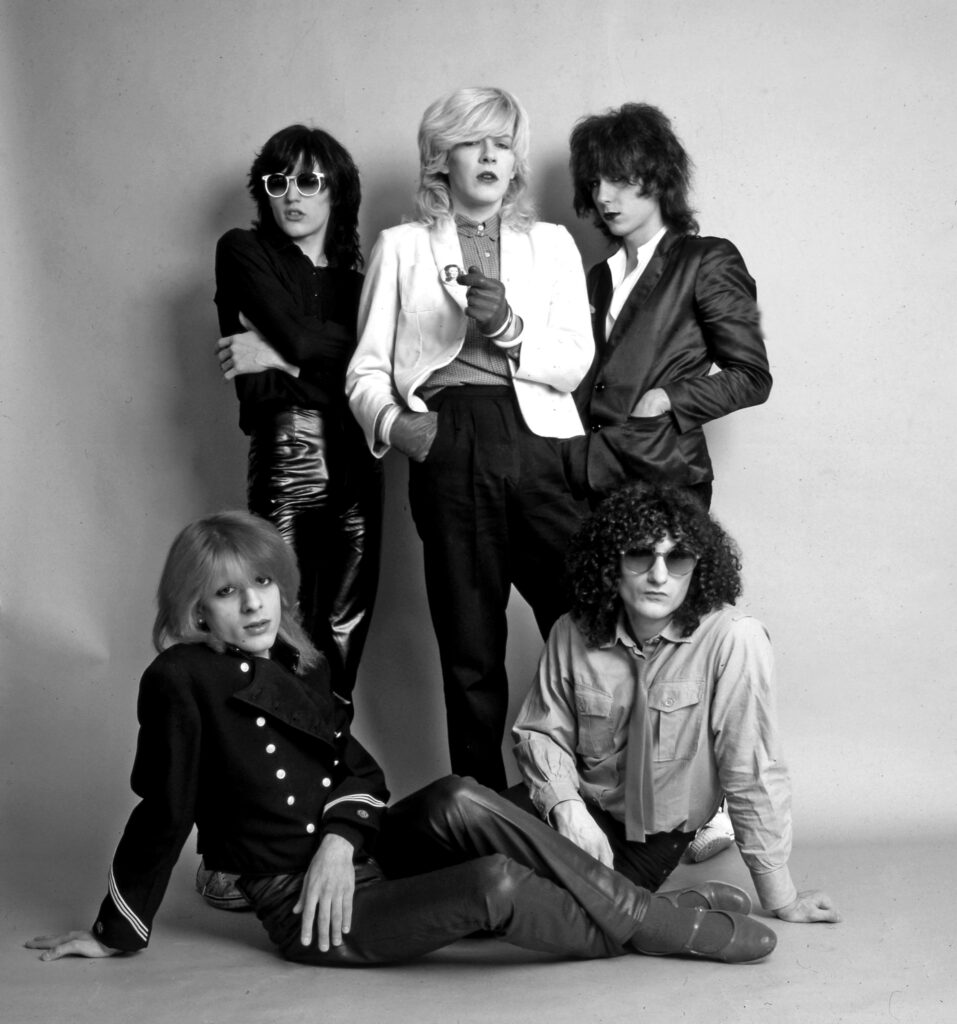

Between 1978’s ‘Obscure Alternatives’ and 1979’s groundbreaking ‘Quiet Life’, pure magic was afoot. Featuring brand-new interviews with all four surviving members, Japan reveal how and why they made the shift from guitar band to embrace the unstoppable synth revolution…

“Here’s a brave new record, it’s Japan, they are number 42 this week with ‘Ghosts’.”

These are the words of broadcaster Richard Skinner on the 18 March 1982 as he ushers a Lewisham four-piece into millions of living rooms for the week’s edition of ‘Top Of The Pops’. What follows is extraordinary. An alluringly-coiffed David Sylvian looks into the camera, his face painted like he’s made of porcelain, while his bleached fringe casts shadows across his eyes. As he sings, he’s accompanied by bare, ambient, Stockhausen-like fragments of sound: a foreboding singular synth line here, a glitchy effect or a singing bowl there. There’s so much sonic space that a twitchy BBC stage technician starts filling the studio with dry ice way too soon.

Then the resolving notes finally start to arrive; a few simulated strings from Richard Barbieri’s synth, a couple more plinks on a xylophone from Steve Jansen, then the chorus is over and we’re back to the eeriness of the verse. Mick Karn, a sui generis of the fretless bass, also mooches on stage with a synthesiser. Minimal it might have been, but ‘Ghosts’ nevertheless jumped to number 16 the following week, and would eventually peak at number five – not bad for a song that some had predicted would be career suicide.

It’s a subtle, sophisticated and self-contained work that was greatly at odds with what was above it in the charts: Bucks Fizz, Chas And Dave and the Goombay Dance Band. In a decade of brash and flash, it’s a song so delicate it is as if it were woven out of silk; an “art rock masterpiece” according to the late writer and theorist Mark Fisher.

But Sylvian’s deeply personal lyrics about unwelcome revenants sabotaging success would help convince him to pursue his artistic journey alone thereafter. Little more than six months later, having begun to achieve mainstream success, and having honed their sound to fastidious perfection, Japan called it a day. Some viewers would have been seeing them for the first time on that edition of ‘Top Of The Pops’ and, given their arty poise and musical prowess, might have assumed they’d fallen from new romantic heaven resplendent and fully formed. Which couldn’t be further from the truth.

Formed in 1974 by the brothers Batt (who would change their names to David Sylvian and Steve Jansen in homage to the New York Dolls) and school friend Andonis Michaelides, (who would become Mick Karn), Japan’s inauspicious first gig took place at Karn’s brother’s wedding. They cut their musical teeth while attending Catford Boys’ secondary school, a rough house institution that mostly served up hard knocks.

“We were not an art school band,” says Steve Jansen, dismissing what many have always assumed. “We attended a comprehensive boys’ school that was governed by a few masochistic ex-military types, as well as some dodgy blokes copping feels and, in some instances, taking boys home. This was the 1970s and kids were victims of all kinds of physical and mental abuse, so it was a case of how best to survive it, and finding a way of improving your self-esteem through making music was one alternative.”

Mick Karn’s esteem took a pounding when skinheads beat him up and stole his bassoon, an instrument he was becoming more than proficient at. He petitioned the school to buy him another, and when they refused, he took revenge by splashing out £5 on a bass guitar. Sylvian had already started playing guitar, and Jansen had taught himself drums. Which begs the question, were skinheads indirectly responsible for the formation of Japan?

“Mick losing his bassoon had nothing to do with the forming of the band,” states Jansen, “it happened quite some time earlier. David and I were playing songs and Mick was a school friend who wanted to join in and he opted for bass guitar.”

Richard Barbieri was the last of the Catford boys to join the band, on keyboards, while an advert was placed in Melody Maker for a guitarist. Rob Dean from Clapton in east London answered their call. Dean was two-and-a-half years older than Barbieri, the hitherto oldest member of the band, and became the last to join in 1975. He’d be the first one out too six years later, just as they were on the cusp of success.

“Yeah, I would have liked to have done ‘Top Of The Pops’ and a couple of other things, but it wasn’t meant to be,” he says on the phone from his home in Costa Rica. “I was off doing my own thing by then.”

In 1978, Japan released not one, but two albums, neither of which did particularly well outside of Japan (the country). Debut album ‘Adolescent Sex’, recorded with Ray Singer who was best known for his work on the Peter Sarstedt one-hit wonder ‘Where Do You Go To (My Lovely)?’, has little to recommend it.

The first single, a cover of the Barbra Streisand showtune ‘Don’t Rain On My Parade’ that somehow compresses all of the camp out of the original version, sank without trace. That was in spite of some gimmicky publicity and some serious outlay on billboard adverts by their German label Hansa, who were best known at the time for being the home of Boney M. One offending poster that made its way across London depicted a woman’s hand reaching into a zipper with the words “Get into Japan” across it.

“We have our old manager Simon Napier-Bell to thank for the tasteless promotional campaigns, which turned much of the press against us,” says Jansen. “I think he probably convinced Hansa that he knew what he was doing, but his methods were from a dying breed of management and, as history shows, he never really understood how to market bands.”

Napier-Bell had looked after the Yardbirds and Marc Bolan in the 1960s and he’d go on to have further success with the likes of Wham! and Sinitta, but he’d been out of the country for several years managing Spanish Filipino singer Júnior before he hooked up with Japan in 1976, and was deeply out of step with what was happening at the time.

It was the year that punk broke, and Japan, with their long, bouffant-y hair and shoulder pads, took their cues from British glam rock and the New York art rockers rather than the less than glamorous pub rock-inspired punks on the UK scene. In that sense, Japan were deeply out of step too.

“There was a stigma attached to our label within the music business,” says Rob Dean. “If something was on Hansa then NME and Melody Maker were going to diss it. And so the credibility part wasn’t there for us. And then we released ‘Adolescent Sex’ and there were these posters all over London. None of the music press liked it because they didn’t like stuff thrust in their faces.”

“There was an artistry with the American new wave artists like Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Television and Lou Reed,” says London-based Richard Barbieri via email. “I think some of those influences are apparent on ‘Obscure Alternatives’. I found the UK acts too raw, basic and directionless, but a lot of cool artists did eventually emerge from that scene: Siouxsie And The Banshees, PiL, Magazine, Ultravox and so on.”

Which brings us to ‘Obscure Alternatives’. Though David Sylvian has called both 1978 albums “mistakes”, there’s more tentative approval from the other members of Japan, particularly Barbieri.

“I can’t relate to the first album in any sense. It’s an aberration,” he says, following his words with a smiley emoticon made from a colon and a round bracket – a surprising addition to the Japan lexicon. “‘Obscure Alternatives’ should’ve been the debut album and I do have some love for it. It has elements of punk and new wave, discordant guitars and tones. There’s reggae, which we listened to a lot in those days, electronics and atmospherics. It was the first instance where I started programming synthesisers and using abstract sounds instead of trying to play the keyboards in a conventional style. Which I couldn’t.”

“It’s a more consistent, cohesive album,” concurs Rob Dean.

The reggae in question is on the track ‘…Rhodesia’, which, thanks in part to some Sly Dunbar-esque rumbling from Jansen, elevates it above the many inadvisable flirtations with reggae and ska attempted in the 1970s by caucasian rock stars. Steve Jansen isn’t so sure: “The drums are not playing reggae except for during the breakdown section, but even then it’s not in the true spirit of reggae.”

‘Obscure Alternatives’ saw them working with producer Ray Singer again, and it fared little better than the first album at home, though pop stardom did at least beckon in the Far East.

“We enjoyed the madness at first,” remembers Dean. “At home we were playing to 200 people at the Marquee Club and then in Japan we were selling out big venues. It was kind of great, but it soon gets tiring not being able to go out and stroll around and go to the shops. It gets old quickly. I’m not complaining about it, it’s just an otherworldly experience.”

“Popularity in Japan kept us going,” deadpans Steve Jansen, “in that it supported our manager to eat in nice restaurants.”

Back home they’d tour with bands they had nothing in common with, namely the Blue Oyster Cult and The Damned, usually meeting with hostility from the fans of the headline act. Supporting the former, they developed a collective steeliness that would avail them through the coming hardships; supporting the latter, they were just pleased not to get covered in gob.

“Mick Karn got a half brick in the head, and someone threw a lit cigarette in my hair and it started to smoke,” says Rob, dryly. “Unfortunately we didn’t get spat on when we played with The Damned. That was saved up for the main act. You never saw so much spit.”

Going into 1979, it looked as though the game might already be up for Japan. But then their fortunes started to change; slowly at first, followed by a burst of popularity that continued after they dissolved (the 1983 live album ‘Oil On Canvas’ became their highest charting release). In the 14 months between ‘Obscure Alternatives’ and what would be the follow-up, ‘Quiet Life’, Japan transformed almost beyond recognition.

The American influences were turned down with a more European aesthetic taking hold, including the cadences and octaval register of Sylvian’s voice. The music went from an extroverted sleazy rock to a thoughtful, introverted hum, and the cluttered middle in songs where guitars fought it out with keyboards became pared back and synth-oriented.

Not many reinventions in pop have been so radical, and there are few clues on ‘Obscure Alternatives’, save the minimal and eerie piano instrumental ‘The Tenant’, of what is to come. So what exactly happened?

“Maturing”, says Steve Jansen with no further comment.

“I think the things we were listening to were changing a lot too,” says Dean. “A lot of electronic music: David Bowie’s ‘Low’ and ‘Heroes’, experimental stuff taking it somewhere else, as well as Roxy Music. We listened to a lot of early Ultravox; Eno, of course. Got to know a little bit of YMO. So it all comes into it.”

“It’s as if we discovered sophistication, subtlety and nuance overnight,” adds Barbieri. “David started writing more on the piano, which produced stronger songs. This lent itself towards more open and spacious sounding pieces and we started to understand how to build arrangements.”

Sylvian booked himself into a tatterdemalion hotel off Baker Street with just a cheap electric piano for company and began writing the songs that would form the basis of ‘Quiet Life’. But first came a fateful meeting in the studio with a musical pioneer. Enter the Father of Disco, Giorgio Moroder. Enter too, David Sylvian, emailing from his hideaway in the New England forest.

Sylvian says that he was looking for “a shift in my compositional evolution that might help propel me away from the band’s determinedly rock-based orientation”. Although he’d first encountered the Italian’s work via the schlagery 1972 composition ‘Son Of My Father’ (“one of the worst pieces of schlock pop ever committed to tape”) he, like plenty of others, would be knocked sideways by Moroder’s danceable innovations five years later. While Sylvian was a fan of ‘I Feel Love’, he was even more impressed by the soundtrack to ‘Midnight Express’.

“It was the propulsive repetition that appealed, which also related to a burgeoning interest of my own in this broad field of development: Kraftwerk, dub music, Steve Reich and the so-called minimalists,” he says.

Moroder apparently owed somebody a favour at Hansa.

“Labels have a habit of trying to match artists with successful producers,” says Sylvian. “His name had been mentioned in passing many times in prior meetings with Hansa. I finally decided it might be worth a shot.”

The session was set up and Japan flew to Los Angeles where they entered the studio with Moroder to record the Sylvian/Moroder composition ‘Life In Tokyo’. Legend has it that Japan had preferred ‘European Son’, but that Moroder had rejected it in favour of a song he could take a writing credit on, which it turned out was a leftover from an abandoned session with Cher for the long-forgotten movie, ‘Foxes’.

“This sounds suspiciously like a managerial conceit to me,” says Sylvian. “I don’t recall the song [‘European Son’] being presented to Moroder as an option. I did have it kicking around, we may even have been performing it live. I possibly had it in my pocket as something to fall back on.”

The singer wasn’t impressed with the cast-off backing track he’d been given to work with, but sought to come up with something in the time he had, chopping the two-chord sequence up and realigning it with a new melody and lyrics.

“You can decide for yourself if the term ‘co-writing’ sounds appropriate,” he demures.

The story goes that Moroder sprinkled his magic dust on Japan, which led them in a new direction and success. It’s a simplified narrative, and given that ‘Life In Tokyo’ was a flop the first time it was released, it only contains a shred of truth.

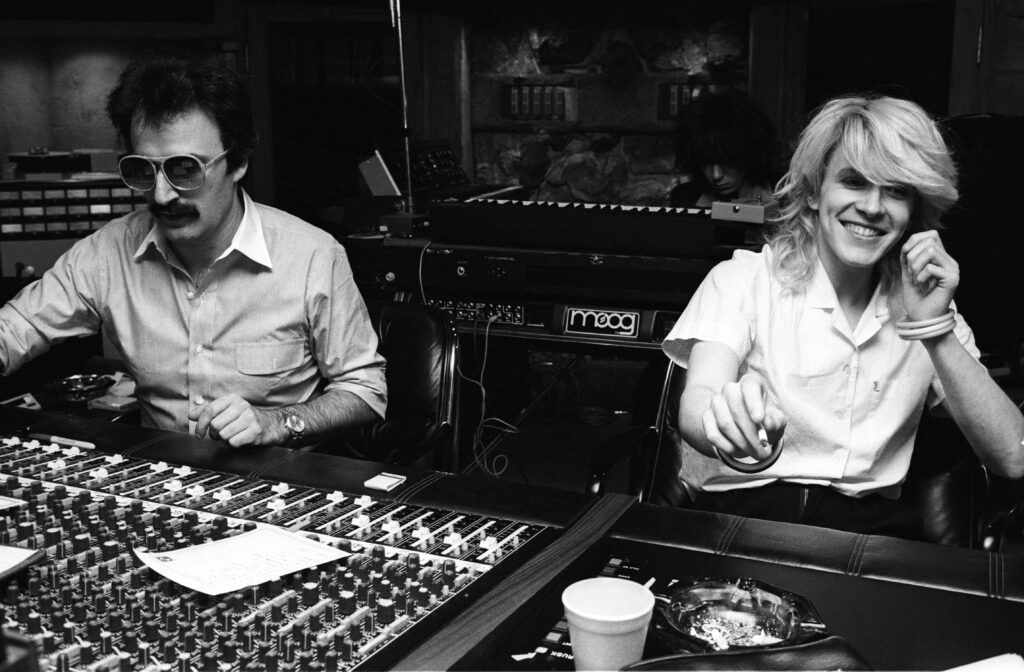

“I think we managed to get through the day in good humour,” offers Sylvian. “It was not a massive learning curve involved for either of us, or so I imagine. I feel myself and the band did the heavy lifting. Giorgio was fairly bemused and laconic. I directed the day’s events and he did his best to support me, which he did with a light touch and considerable self-effacement.”

There’s a photograph [left] of Moroder at his mixing desk with his sleeves rolled up and David Sylvian, still with the shoulder length blond hair, sat beside him, laughing, looking every inch the “cross between Mick Jagger and Brigitte Bardot” that Simon Napier-Bell had once observed.

Moroder apparently astonished those in the room when he claimed he couldn’t operate the banks of equipment behind him, with engineers brought in to control the hardware.

“‘Life In Tokyo’ was a very short, economical kind of session,” remembers Dean. “Moroder had his drums set up, he had his keyboard player, his singers, all that stuff. It was a controlled environment, which ultimately wouldn’t have worked for any further collaboration. Besides, he’d just won an Oscar for ‘Midnight Express’ so his head was probably elsewhere.”

“He’d been wrong to dismiss the crossover that artists like myself and Sparks [whose ‘No. 1 In Heaven’ he had recently finished producing] were aiming for,” says Sylvian, who points to Moroder’s subsequent work with the likes of Blondie and Bowie as proof.

Steve Jansen recalls a “rather boring session, through it was no one’s fault. We were all on a mission to get the thing done in a matter of hours”.

Did he think the gospel backing vocals were a bit much?

“Odd question,” he retorts. “Do you feel they are a bit much? I don’t like the track at all.”

Even if Giorgio Moroder’s studio wizardry was less awe-inspiring than might have been expected, crossing his path could still be considered the catalyst that set Japan off in a new direction that would ultimately lead to stardom.

‘European Son’, though not recorded with Moroder, imitates his style. It also features “quiet life” and “Polaroid” in the lyrics, words that would come in handy for later album titles (though there’s no mention of a “tin drum”).

‘Quiet Life’ itself arrived in 1980, a staggering leap forward. The hiring of Roxy Music engineer John Punter as a producer was a boon, and helped consolidate the work that Moroder had started. Sylvian hadn’t found the right foil until now, but with forethought he’s worked well with a number of musicians ever since, whether that be Ryuichi Sakamoto or Holger Czukay.

“I work well with most people,” says Sylvian. “I do my research, I’m fairly clear on what it is I’m looking for from any given musician I’m working with.”

If Sylvian comes across as serious at times, a resounding endorsement to the contrary comes in the unlikely form of Johnny Marr, who I happen to be interviewing around the time of writing this article.

“I think David Sylvian was one of the greatest kinda hang outs that I ever had, actually,” Marr told me. “It was only two years ago. He was a fantastic guy. I don’t think people realise just how funny he is. He’s really playful and he laughs a lot.”

‘Quiet Life’ featured the best songs of the band’s career up to that point: ‘Alien’, ‘In Vogue’, the mesmeric ‘The Other Side Of Life’… the new balance in the mix, thanks to Punter and Japan’s all-round improvements as musicians (and writer), helped create a new avant-pop that would become highly influential as the 70s became the 80s.

The band’s remade and remodelled image also coincided with the emergence of the new romantic movement, a scene Japan wanted nothing to do with, but who became its inadvertent godfathers anyway.

“It was a very enjoyable album to make and a lot of that was because of John Punter,” says Dean.

At first everybody was happy, but the pursuit of a more synthetic sound would eventually leave the guitarist scratching his head. If you listen closely to the title track, his offbeat guitar hook sitting subtly in the mix gives the music an unmistakable vigour, and his ebow elsewhere brought cohesion where there had been confusion before. Dean would play on fewer and fewer tracks as time went on, and ‘Gentlemen Take Polaroids’ would be his last hoorah with Japan.

“It would have been nice to have appeared on every track, but I also feel that if the track doesn’t warrant it then why do it?,” he says, diplomatically. There was also talk of the band moving to Japan for six months to write and record together, a move he balked at and which may have provided him with his decision to leave.

“The rest of them, they were each other’s best friends,” he says. “They were this unit together because they grew up together, whereas I had friends outside of the band. The people I liked to socialise with were in London, so I didn’t want to go to Japan. I didn’t want to be tied to these four other people and nobody else.”

There’s somebody we haven’t spoken about much up to this point, whose musical development had begun to get him noticed beyond the confines of Japan. The Mick Karn sound became a distinguishing feature of 80s pop music, a slick, communicative, alien voice that also sat perfectly on the albums of Kate Bush, as well as on his own solo record, ‘Titles’. It’s well documented that there was a competitiveness between Sylvian and Karn, and that Yuka Fujii, once the girlfriend of Karn, began a relationship with Sylvian, effectively ending Japan.

“Well, the thing is they were close friends, but they also had their own agendas,” says Dean. “There was this teasing thing going on all the time when we’d rehearse a song, and if a song wasn’t going very far, Mick would be, ‘Okay, well I’ll keep that one for my solo album’. He’d do that all the time. He was always hanging this solo album over David’s head.”

Tragically, Mick Karn died in 2011 from cancer. Naturally he’s the only member of the band missing from this piece.

“I think once he got his fretless bass he just took off,” says Dean. “Having frets on the instrument restricted him and once he bought a fretless bass, he just soared. But also I think it’s the chemistry he had with Steve Jansen as a rhythm section. They played so closely together it was almost telepathic. I guess the best rhythm sections are like that.”

What was it like to play with one of the great innovators of the bass guitar?

“We were inspired by great players and wanted to explore our own options and techniques as self-taught players,” says Jansen. “Mick expanded the role of bass playing in that he avoided fulfilling the traditional role of stamping the rhythm and punctuating root notes, he was instead putting out melodies a lot of the time while rhythmically dodging all over the place.

We would find ways of not playing together as a rhythm section that sounded as though we were. It’s not often that you’ll sing a bassline rather than the vocal melody.

So did Kahn and Jensen develop a musical telepathy?

“If Mick and I were sitting together reading that question, we’d both laugh, if that’s some kind of telepathy?”

After ‘Quiet Life’, Japan would stop being the sum of their influences and would, for a short time at least, become a peerless, immaculate, living work of art, leading where they used to follow, inadvertently creating the template for pop superstardom that others would reap the benefits of. Their pristine image still haunts us, as does the alternative future in which they never split up.

‘Quiet Life’ is being re-released as a deluxe edition by BMG

David Sylvian – ‘Secrets Of The Beehive‘ 180g Gatefold Sleeve Vinyl LP

£25.00

Sylvian’s move from enigmatic pop star frontman with Japan to even more mysterious solo artist was cemented in 1987 with the release of this extraordinary album. This melancholic masterpiece blends ambient, jazz, and art rock elements with introspective lyrics and lush arrangements, the album showcases Sylvian’s evocative voice and atmospheric soundscapes. Collaborators include Ryuichi Sakamoto, former Japan drummer Steve Jansen and film composer Mark Isham (‘The Hitcher‘).